How the Seasons Affect Water Availability in Western Kenya

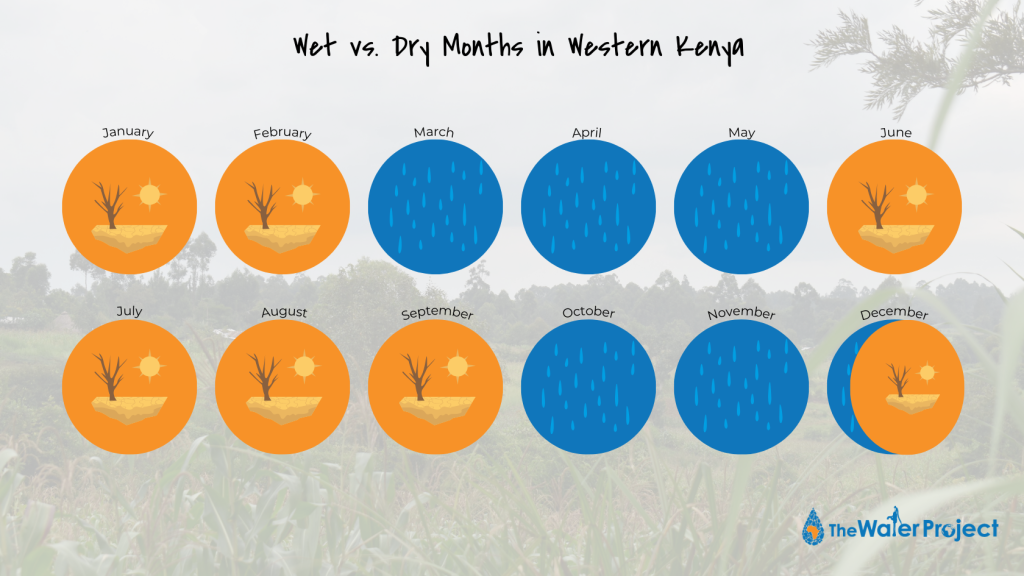

Where most of The Water Project’s work has taken place, in Western Kenya, there are wet and dry seasons rather than hot and cold ones.

But, as we heard from staff and community members living in Western Kenya, climate change has affected the length, duration, and severity of the rainfall patterns in each of these seasons. The erratic weather in recent years has made growing food difficult — and created extensive problems for those living without adequate safe water.

The Changing Norm

“Most parts of Kenya experience two rain seasons: March to May’s long rains and October to December’s short ones,” explained Olivia Bomji, Impact Communication Officer at The Water Project’s Regional Service Hub in Western Kenya.

“The months of June to August are mainly cool and dry over most parts of the country, except for some areas here in [the] western region that get rain. The first [dry season] runs from December to March, which is the country’s summertime.”

In this region, more than 70 percent of people are farmers, which adds urgency to predicting the weather — and the planting season.

Olivia said: “20 years back here in Western Kenya, there were two different seasons that were known to everyone, and those staying in the village could tell when it [would] rain or not through studying the clouds and wind patterns. Recently, Kenya’s rainfall patterns have changed, and this has been linked to climate change.”

“In recent years, [the] delay in the coming of rains has been the norm. In other years, rains came on time, but then stopped earlier than anticipated. Research shows that rainfall is reducing while temperatures are on the rise in Kenya, as is the case in other countries in the Horn of Africa.”

The Dry Season

When the rains stop, so too does the easy access to water in Western Kenya.

“During [the] dry season, most of our schools and some of the communities here in Western Kenya spend most of their time looking for water to drink,” Olivia explained. “This is because the concrete tanks in schools are dry because they depend on rainwater. [The] dry season affects most schools here in Western Kenya and the students are forced to go back to their old ways of carrying water from home or fetching water from different sources in order to fulfill the water need in school.”

“Some of the communities’ water points go dry because they are seasonal in nature, and this really affects women and children because they have to queue or walk for longer distances to fetch water from the neighboring communities. [For] some of the springs, the discharge of water reduces, and this causes long queues and conflicts among the community members because everyone wants to fetch water first to avoid the long queues.”

This situation is true for 14-year-old Faith from Shikose Community, who was forced to stay out of school for a period during the dry season. The pool from which everyone in her community fetches water all but disappears during the dry season, so she’s forced to travel longer distances to find water for her household in the dry months.

“During dry seasons, my mother forced me to wake up very early in the morning to fetch water for drinking [and] for her to prepare breakfast for the family,” Faith said. “I remember this year during [a] dry spell where I did not go to school because I had to wait for a longer period of time to fetch water.”

The Rainy Season

“During the rainy season, things are very different,” Olivia said.

“Community members are able to fetch water comfortably without queueing and fighting at the spring to fetch water, although the quality of water is questionable. Most of our springs are located down [a] slope, and all the rains wash all the dirt down to the spring. This means that the springs without well-placed cut-off drainage will be affected, meaning all the dirt will go through the spring, and the quality of [the] water will be questionable.”

One real-life example of rainy season issues is in Chombeli North Community, where 13-year-old Algiers suffers from water-related illnesses due to the drop in drinking water quality during the rainy season at his community’s unprotected spring.

“All is not well for me,” Algiers said. “I have just recovered from sickness last month before we opened school. I have been infected with waterborne diseases, which [have] really affected my academic calendar. …Also, my parents have been affected financially due to medication and other transportation costs. The source is not safe for fetching water, especially during [the] rainy seasons when the collection area overflows.”

How The Water Project Helps

Whether the people of Western Kenya are facing water shortages during the dry season or water-related diseases during the wet season, their need for reliable, clean water sources is obvious.

With all we’ve learned about the variability of Kenya’s weather in recent years, our strategy for providing water here is ever-evolving. To address water shortages during lengthening dry seasons, we vet each water resource we transform into a safe water source.

For protected springs, this means asking important questions. Before we consider protecting a spring, we survey whether the spring has ever gone dry, if water-guzzling eucalyptus trees are close, if a nearby farm might allow fertilizer or chemicals to seep into the water, and how much time it takes to fill up a standard jerrycan from the source. All this data combined tells us whether we can convert an unprotected spring to a protected spring and expect it to provide safe, reliable water for years to come.

As of 2022, we also install chlorine dispensers at every single protected spring, so water users have the option to purify their water before taking it home for added peace of mind. So, even if the spring’s water quality diminishes during the rainy seasons due to storm runoff, no one has to worry.

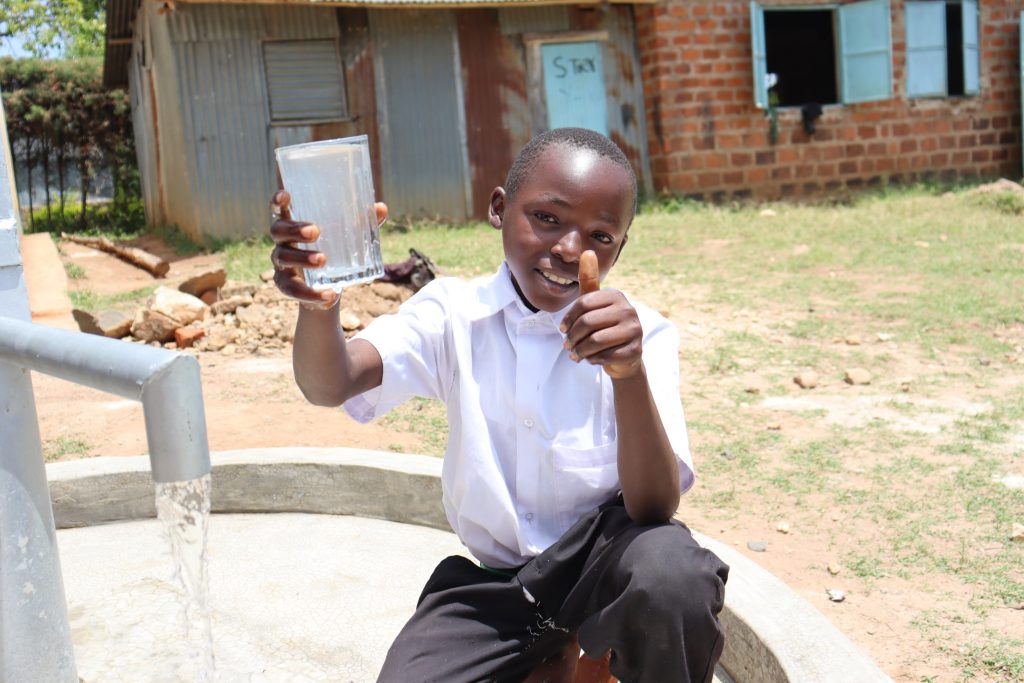

In schools, we no longer install rainwater harvesting tanks in Western Kenya, as we can’t rely on the rainfall to provide consistent water. Instead, we’re investing in borehole wells, which draw from groundwater surveyed by our staff hydrogeologists. Borehole wells are often more expensive to install, but they help us know that we’re providing consistent water and solving the water issues the community once faced.

“The Water Project has ensured that communities and institutions have access to reliable, clean, and safe water despite the changing weather patterns,” Olivia said. “And men, women, and children’s health, hope, and dreams have been restored.”

The impact of climate change on water availability is not just a statistic — it’s a reality affecting the lives, education, and health of communities in Western Kenya. The Water Project’s initiatives in protecting springs, installing chlorine dispensers, and investing in borehole wells make a real difference in the lives of those who face the daily challenge of accessing clean, safe water.

Each story of a child missing school to fetch water or a family struggling with waterborne diseases is a call to action. By supporting The Water Project, you become part of a community committed to changing these narratives. Your gift will provide reliable water sources, ensuring children like Faith and Algiers can attend school regularly and live healthier lives.

Home More Like ThisTweet