Resource Demands of Bottled Water

Shannyn Snyder

Privileged consumers are in a romance with the bottled water industry, with aerosol-canned Evian touted as the fountain of youth and square-shaped Fiji water a status symbol among the Hollywood elite. However, with new studies exposing both the chemical and impurity content of many leading brands of bottled water, and the fallen economy leading most U.S. consumers to spend more responsibly, it seems even more timely for bottled-water drinkers to change their habits.

The irony of the single bottle of water, typically representative of a healthy beverage in a convenient container, is that it takes 3 or more liters of water to make 1 bottled liter, and many water bottlers are given carte blanche rights to mine local groundwater supplies at the expense of local populations.

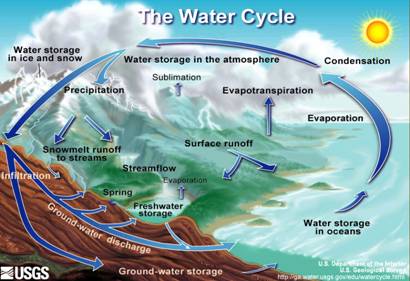

Using the below water cycle illustration, it is important to note that the simplistic view of water cycle requires, at a minimum, that precipitation from the atmosphere must restore groundwater. This groundwater eventually evaporates and the cycle begins again. But what happens to this water cycle when water is consumed and never replenished? A conservationist may plant trees for reforestation, for example, but there is no congruent solution for returning consumed water to the ecosystem.

According to the Canadian Environmental Law Association, removing

water for bottling is a form of consumption, and although beverage

companies abuse water resources, consumers who purchase the commodity are

essentially sharing responsibility for stressing the environment.Mining water faster

than it can be replenished is already causing some water scarcity in

the U.S., where most of the population is still enchanted by the ability to

run an unlimited amount of water from a tap.

According to the Canadian Environmental Law Association, removing

water for bottling is a form of consumption, and although beverage

companies abuse water resources, consumers who purchase the commodity are

essentially sharing responsibility for stressing the environment.Mining water faster

than it can be replenished is already causing some water scarcity in

the U.S., where most of the population is still enchanted by the ability to

run an unlimited amount of water from a tap.

Remembering that "water barons" bottle water for profit and not for any other reason may be one way to refocus attention on where the water comes from, and that degradation of springs and other aquifers will more noticeably impact communities in the coming years.

In fact, in her September 2008 to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, Wenonah Hauter, Executive Director, Food & Water Watch testified that consumers are being mislead by water bottlers and that the product lacks environmental and safety regulation. Aside from the fact that bottled water source is often tested only once per year for contaminants versus the required monthly testing of tap under the EPA's Safe Drinking Water Act, bottled water manufacturers do not have to report testing results to consumers, and the quality of the water is subjective. Hauter's concerns also touched upon the environmental impact of mining water, stating:

When the flows and levels of a region's springs, wetlands, lakes, streams and rivers are materially affected from extraction for bottling, the entire local and even regional environment suffers, and this extends to the activities that depend on the water-agriculture, individuals, businesses, tourism and recreation. No one knows how much water is being mined for bottled water because there is no universal requirement for bottled water companies.

Hauter's comments reference the limits that are often set for residents who face water shortages due to drought, but beverage corporations are able to draw millions of gallons of water from local ground sources without regard to the impact on the local community. Nestle's impact in McCloud, California is just one example of how a transnational bottling company can turn a community upside-down.

Over-mining of aquifers without allowing adequate replenishment can adversely affect the ecosystem, but unless the issues become a shared nationwide concern, the depletion felt by "others" will likely never quite hit home. While various water bottlers rake in profits in even a downturned economy, a growing number of Americans will experience water problems in the future, from use shortages to pollution. It's not just a "third world" problem.

For more information on national water conditions, current groundwater levels and a U.S. streamflow map, please visit the U.S. Geological Survey.