Why Does The Water Project Work in Africa?

This is the first entry in a series where we answer questions we’ve received from curious donors, website visitors, and casual commenters.

As we’ve said before, it can be difficult for those of us who have always had water piped into our homes to understand what it’s like not to have water. We haven’t needed to trek long distances, brave harsh wilderness, wait in long queues, or dig scoop holes into dry riverbeds to obtain often-contaminated water. These human experiences are at the core of what we aim to alleviate, but the water crisis is massive, nuanced, and ever-changing.

Our staff, both in the United States and overseas in our target areas, live and breathe water, sanitation, and hygiene—and yet we’re still learning new things every day. This series aims to share what we’ve learned along the way with anyone skeptical, curious, or (our favorite) thirsty for knowledge that can help solve the water crisis facing our global community.

Today’s Question: Why does The Water Project work in Africa (rather than in the United States)?

The simple answer to this question is that the need for clean water where we work in sub-Saharan Africa is much higher than anywhere else in the world. But, as in most simple answers, there’s a lot more to it than that.

All living creatures on Earth need water to survive, including us humans. But water isn’t only for drinking. It’s necessary for cooking, cleaning, bathing, laundering clothes, washing dishes, watering farms or gardens (a primary food source for many in sub-Saharan Africa), performing religious rites, and more. Where water is scarce, health deteriorates rapidly as hygiene standards fall.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), children are 14 times more likely to die in sub-Saharan Africa than their counterparts in more developed countries. This doesn’t have a single cause, but one of the most significant contributing factors is a lack of safe, accessible, and reliable water. In Africa, diarrheal disease is the second leading cause of death for children under five (interestingly, malnutrition is the first leading cause, which can be caused or exacerbated by diarrhea from waterborne disease). Better access to uncontaminated water could prevent most of these deaths.

But only 44% of schools in sub-Saharan Africa have a water source on school grounds. Students and staff must sacrifice things like handwashing and cleanliness when water is not readily available. This difficult circumstance exacerbates the likelihood of diarrhea and other diseases.

As a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WaSH) organization, one of our goals is to equip children and parents with knowledge. We couple every project we implement with training sessions where we cover topics integral to improving health: handwashing, water handling, disease transmission, and more.

In wealthier nations, children are reminded to wash their hands by parents, guardians, teachers, posters in bathrooms, and even Paw Patrol. But in sub-Saharan Africa, we often hear from communities where we work that these concepts are new to them.

“Being an uneducated person, some of the things that we believe are most times complete lies,” said 55-year-old farmer Alie Sesay, whose community well was rehabilitated earlier this year.

“I have always believed that eating oranges will lead to malaria, but based on the training, I have learned that is not true. Keeping our environment clean keeps illnesses away and prevents future hospital visits. I have to be honest, I have used native herbs more times than I have been to a hospital for myself and my family. Most of the illnesses are a result of what we do to our water and food.”

“Before this time, I thought most illnesses are related to witchcraft attacks or a curse from [our] ancestors,” said N’mah Yillah, from Menika community. “But now, I fully understand that we are the cause of our sickness due to the things we do.”

In sub-Saharan Africa, it’s difficult for children to attend school: over a fifth of children between the ages of ~6 and 11 don’t go to class. And it only gets worse as children grow older. Just a third of children in sub-Saharan Africa between the ages of 12 and 14 go to school. Parents may be unable to pay school fees, schools are too far away, or girls drop out of school when they reach puberty. But when we interview kids about why they can’t attend school, they mostly talk about illness due to drinking contaminated water.

“[I] have had a number of cases where I had [a] fever and [was] forced to stay at home while other pupils were at school, which I don’t like,” said 12-year-old Glen. We plan to protect his community’s spring sometime this year.

“It makes me drag behind in terms of performance in my class, and all this is because of using contaminated water, which we don’t have an option for now.”

Isn’t There a Water Crisis Everywhere?

Of course, there is a water crisis worldwide. There is even a clean water shortage in the United States where The Water Project is based, and not just Flint, Michigan’s lead-laced water fiasco.

In addition, climate change affects water access in the U.S. and around the world. Presently, California is in the midst of its worst drought in 1,200 years and is employing rationing measures to ensure everyone continues to have access to water. Historic droughts are being reported across the country, concentrated in the nation’s southwest regions.

According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 3% of people in the United States lack access to clean water—many of those people are low-income or marginalized.

The reality is that our entire planet is facing a water crisis.

Unfortunately, due to various factors, many of the issues facing the world are worse in sub-Saharan Africa. There, climate change, lack of infrastructure, corrupt leadership, and years of oppression have all collaborated in undermining water availability. There, lack of water exacerbates poverty rates, hinders access to education, increases health problems, compounds gender inequalities, contributes to food insecurity, and much more.

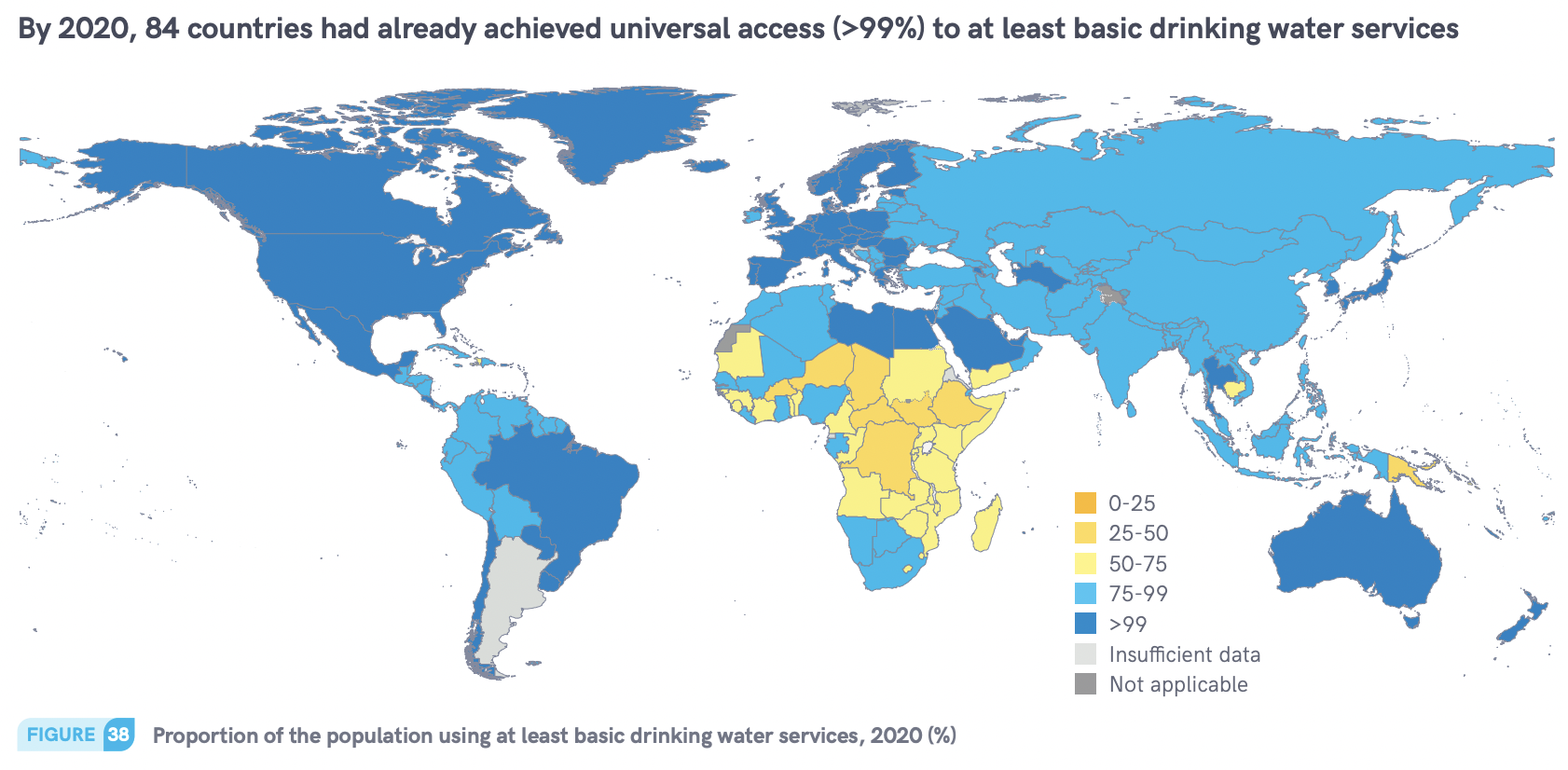

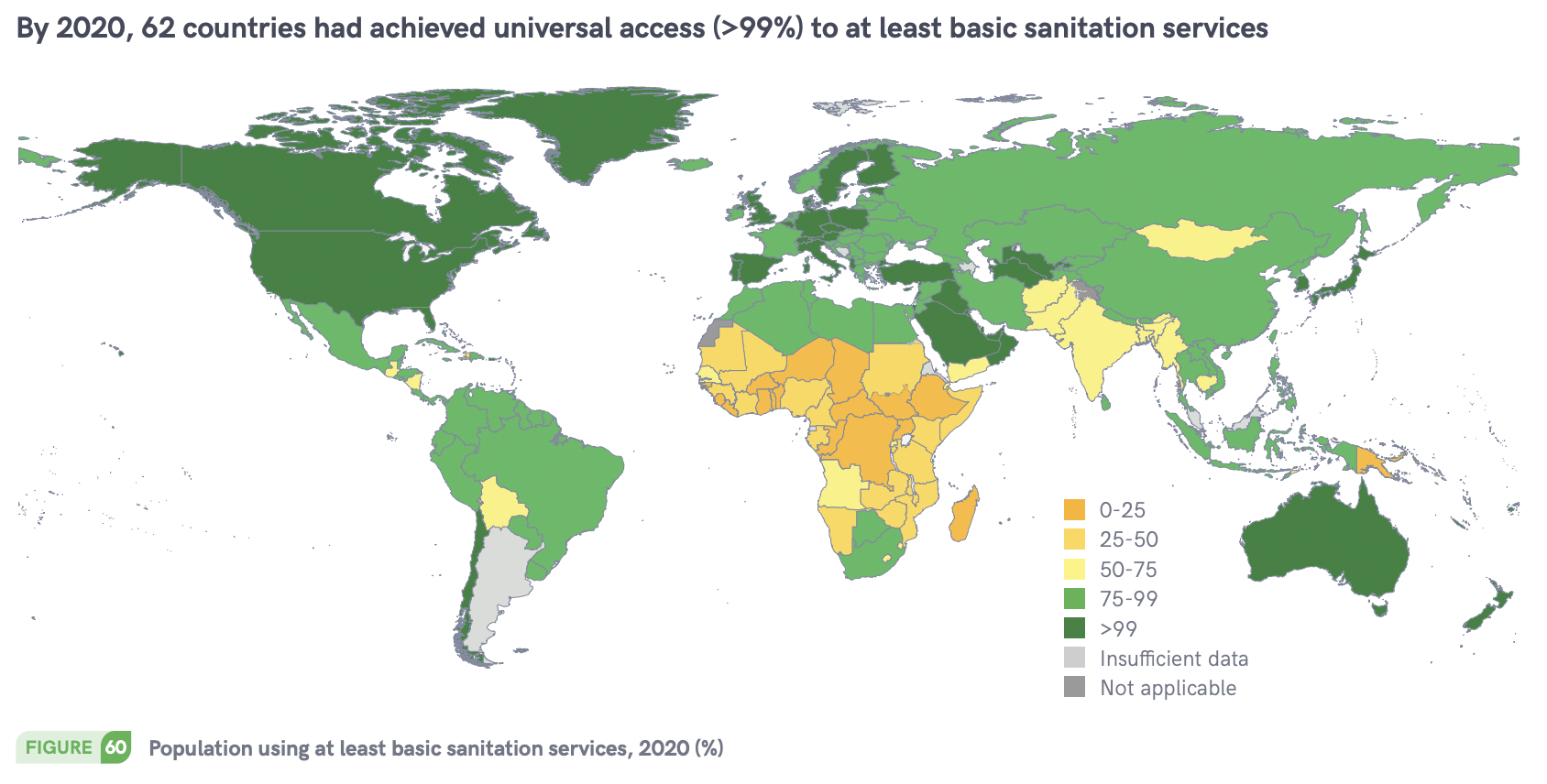

The below maps from the UNICEF and WHO’s Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) display how poorly sub-Saharan Africa ranks against the rest of the world regarding drinking water and sanitation services.

Percentage of people worldwide with access to basic water service. (JMP)

Percentage of people worldwide with access to basic sanitation. (JMP)

So, yes, the whole world needs help when it comes to water. But in sub-Saharan Africa, it’s an even harsher challenge with the potential for a more significant impact.

Basic water access means collecting water from an improved source within a 30-minute round trip—including the time it takes to wait in line and fetch the water at the water point.

Worldwide, some 771 million people lack access to basic water services, and half of these people live in sub-Saharan Africa.

Through your support, The Water Project works with communities to ensure every person has at least basic access to water every day of the year.

Conclusion

If you aim to help solve the water crisis in your own community (because there likely is one), please give generously and often! Any impulse to improve the fate of the Earth is an excellent one that we at The Water Project support wholeheartedly. Feel free to search for a reputable non-profit aligned with your goals.

Our planet provides enough resources for everyone. There’s plenty to go around. But sometimes, well-intentioned people need to band together to ensure those resources reach the communities most in need. When it happens, it’s a beautiful thing.

If you’re ready to join us in tackling the water crisis in sub-Saharan Africa, read the stories of impacted community members to decide who you’d most like to help. Their voices are frequently more compelling than a blog article ever could be.

If you ever find yourself curious about something to do with the water crisis, contact us. Your question might end up as our next blog article!

Home More Like ThisTweet