Deep Dive on Drought: What is The Water Project Doing to Counteract Its Effects?

We think a lot about rain at The Water Project. Rain is a critical component in solving the global water crisis. It is also something we cannot control. So, we spend a lot of time monitoring and tracking rain in the places where we work. Too little rain can cause a borehole to run dry, while too much rain can wash out a brand-new sand dam.

Wherever you get your news, you’ve probably heard something about substantial droughts or floods accelerated and exacerbated by climate change. The worst drought in 40 years in East Africa is expected to worsen with another poor rainy season. According to the latest projections, some 22 million people in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia are on the brink of food scarcity, and parts of Somalia are expected to experience famine. Unfortunately, in these times of constant weather turbulence, just about every region on Earth either suffers from a lack of water or is experiencing significant damage from extreme precipitation events—sometimes in rapid succession, though this seems counterintuitive.

Drought: Problems Upon Problems

On the surface, drought seems like a straightforward challenge: rains don’t come, which causes problems for all living creatures depending on water. But drought itself is complicated.

“80-90% of natural disasters in the last ten years are from floods, droughts, and severe storms.” – World Health Organization

To the casual observer, drought shrinks bodies of water and shrivels plants. But a lack of water on the planet’s surface has compound effects on the layers of earth beneath us, from which our cleanest drinking water comes.

When rain doesn’t replenish a region’s water table, water points that once had a steady supply fail. The increased temperature and dry conditions evaporate water on the surface more quickly, so no water trickles down through the layers to replenish what has been lost.

When rains do finally come, this lack of water in the ground enables flooding. The earth is dry and compacted after a drought, meaning new rainwater can’t replenish underground water reserves. At the same time, the likelihood of wildfires and other natural disasters increases.

And those are just the effects on the earth itself.

Eight-year-old Patrick walks on a dry riverbed where water once flowed in Southeast Kenya.

Droughts spark famines like the one in the Horn of Africa, with crops dying from lack of water. People can’t perform critical hygiene routines, such as handwashing with soap after using the bathroom, without water, which increases infectious disease and malnutrition caused by diarrheal disease. As more and more humans and animals (including livestock) succumb to the ravages of drought, countries’ economies—and their trade partners’ economies—suffer.

Both short- and long-term droughts occurred long before humans began to record weather patterns. But our population is rising, and so too is our need for water. Our planet is suffering from detrimental changes to the water cycle that recharges groundwater (in part due to deforestation and climate change).

Descriptors like “historic” and “unprecedented” for the droughts and floods happening worldwide are actually accurate.

Building Resilience

Our work provides immediate benefits to those who have contributed the least to the disruption in Earth’s normal functioning (unlike some celebrities who were called out recently). Yet, the people who contribute the least to climate change endure some of the worst of its effects.

“One of the things I (and many others) find so troubling about climate change is the incredible inequity that acts both as a driver and result of the crisis,” said Emma Kelly, The Water Project’s Program Manager.

A scoophole in Tondora, Kenya – a community where we hope to install a sand dam in 2023.

“When we think about climate change and the effect that it has on our day-to-day lives, we should think about our relative levels of exposure to the impacts of climate change, our susceptibility to negative effects, and our ability to cope with or manage them.

“Low-income countries lack the infrastructure which makes high-income countries resilient to natural disasters (think sea walls during floods, and large reservoirs feeding municipal piped water systems during drought), and are less able to cope with or manage the aftermath of climate disasters due to gaps in public service provision and healthcare systems. This means that as the climate crisis continues and worsens, the disparity will widen as high-income countries make money off of carbon-generating activities and low-income countries face huge economic losses and loss of human life.”

Our teams and communities partner to strengthen our water projects’ sustainability and implement practices that ensure our water sources remain viable for years to come.

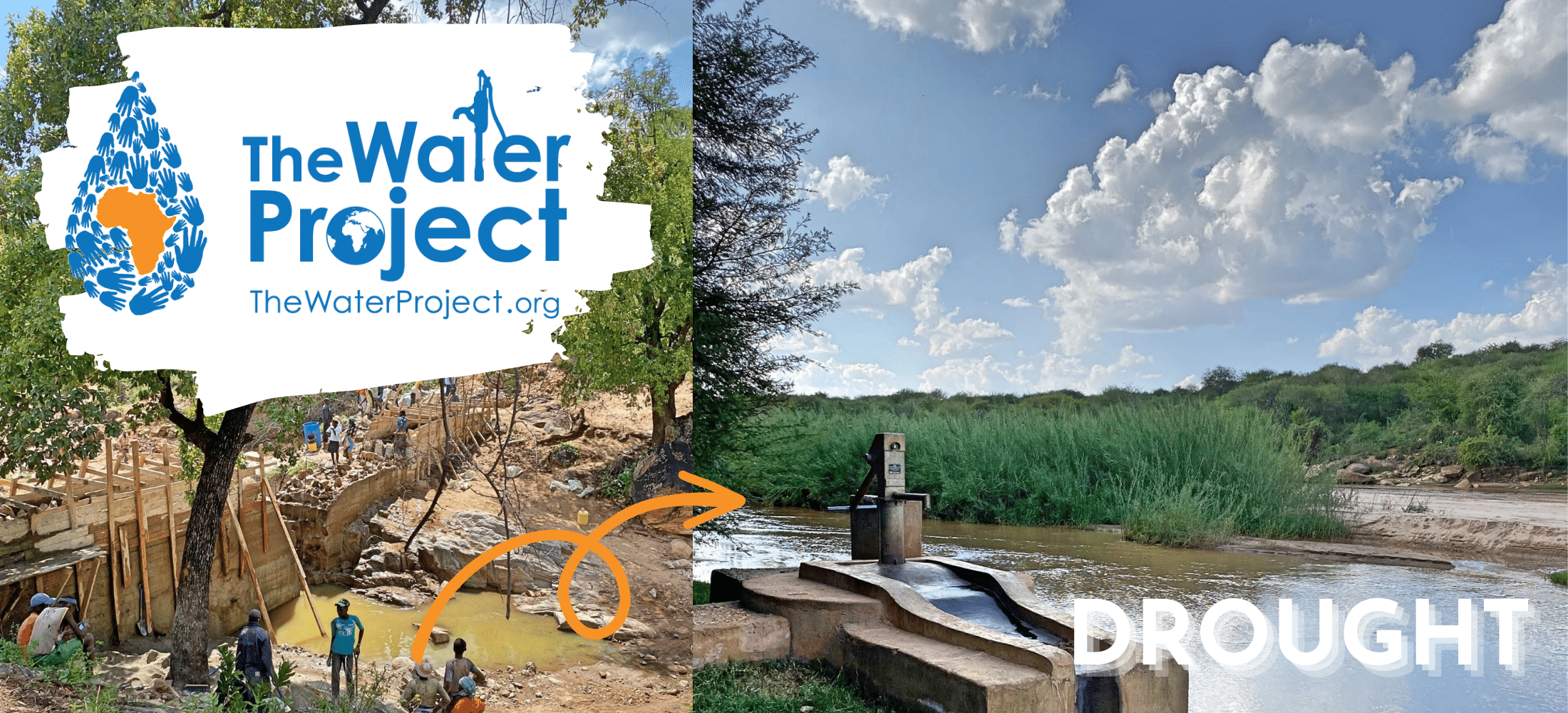

One of our most cutting-edge methods to combat climate change is through sand dams, which we regularly install in Southeast Kenya. This semi-arid region goes through long periods without rain each year. People there will walk for hours daily to seasonal riverbeds, where they must dig holes into the ground to access water stored below the surface. For a few years, extended periods of drought have ravaged this area. The current drought facing the region is expected to continue into 2023.

Emma saw sand dams firsthand during her visit to Kenya in mid-2022; she was surprised at the differences between sand dams and the ones we’re familiar with in America.

Sand dams are often built on seasonal riverbeds that disappear in the dry season. Instead of holding back a pool of water, sand dams accumulate a reservoir of silt and sand. During a sand dam’s first rainy season after construction, the sand will capture 1-3% of the river’s flow. Almost all of the river water flows over the dam. Then, shallow wells constructed on the riverbank can provide water even when the river has dried up, thanks to new groundwater reserves.

Emma said: “The Water Project is so excited to be involved with the construction of sand dams in Southeast Kenya, which provide a reliable water source in drought-prone areas, greatly benefit the environment, and do not harm communities or the environment downstream.”

The first step in building a sand dam is to dig a deep trench in the ground that reaches bedrock so the dam will have a strong foundation.

“The sand dams also improve their surrounding environments,” she continued. “As water gathers around the sand dam, plants start to grow. This, in turn, increases rainfall and helps revive the surrounding region.”

Emma also explained how plants encourage rain. “Especially in tropical areas, changes in patterns of vegetation have both physical and chemical effects on the atmosphere by mediating the flow of moisture, energy, and trace gas particles.

“When we look at a forest or heavily vegetated area, we see deeper roots, higher levels of leaf cover, and more biodiversity than, say, a pasture with no trees. Deeper roots contribute to better groundwater recharge and also mean that the vegetation is able to absorb more water from the soil. This moisture is shared with the environment through transpiration, or a release of water into the atmosphere during the photosynthesis process. Higher leaf cover provides more surface area from which water can transpire and also can cool the ground through shade, reducing evaporation during dry spells and allowing the soil to retain more moisture. All of this exchange of water between the vegetation and the atmosphere affects the patterns of rainfall in the area.”

Layers of cement built up over weeks of work.

As you can imagine, building these gigantic walls of sand and rock requires an enormous cooperative effort. To construct one sand dam, dozens of community members work ten-hour days, six days a week for about a month. But as community members build up the dams layer by layer, they know they are creating better lives for themselves and future generations.

Future Outlook

“While it is incredibly important that we as a society work to reduce carbon emissions and slow the pace of climate change, those processes are slow-moving, and the effects of climate change are already being felt by many people living in low-income countries,” Emma said. “The water systems provided by The Water Project are part of a toolkit that will allow people to build resilience to the detrimental climate effects they are already experiencing.

“Access to reliable WASH services improves the health and well-being of communities by reducing rates of infectious disease, breaking down barriers to school attendance, and giving women and children back the time they used to spend fetching water. However, the systems we implement also represent an effort to reduce the disproportionate burden of climate change on the communities we work with. While The Water Project may not have the ability to reduce their level of exposure, we are giving people in Southeast Kenya some of the tools that will make them less susceptible and more able to cope with climate change.”

A working sand dam with water flowing overtop. Notice the lush greenery surrounding the structure!

Tweet