People, Places, and Puddles: Our Approach to Increasing Water Coverage

Let’s say you’re a school-aged child in sub-Saharan Africa (hypothetically). You don’t have piped water at home. The Water Project has just visited your community and installed a new water point, where someone comes regularly to test the water and ensure it’s safe to drink. Under the best circumstances, the water source never goes dry, and you can always fill your jerrycan with water that won’t make you or your family sick.

But you live on the edge of a community and, while the new water point sits in a good spot for most people, you can’t reach it easily. It might be a long walk away, in the opposite direction from your school, or at the wrong end of hilly, rocky, muddy terrain.

So when your school asks for all students to carry water to class each day, you despair, not wanting to walk all that way every morning before continuing to school, especially when the journey to school might be another trek. Instead of ending up late to school, you opt to stop at another water source — a pool of water on your route.

“Water is a system of people, places, and puddles,” said The Water Project (TWP) CEO and founder Peter Chasse. “We know that knowing something in our brain doesn’t always translate into behavior. Sometimes, the puddle on the way home wins because it’s closer or more convenient.”

At school, you drink dirty, contaminated water. Sadly, the clean water you get at home will not cancel out any waterborne pathogens you ingest at school. As a child, your immune system is still developing, so any illnesses you contract have a higher chance of creating long-term effects or even killing you. Every sip of dirty water is a risk.

Things would be better if you had a water source close to home or on your way to school. But they still wouldn’t be solved.

Students who carry water to school often pour the water they bring into the same storage facility.

So all the other students at your school would have to collect water from clean sources for the water at school to be clean. Really, the only way for you to drink clean water at all times is for you, your school, and your fellow students to have clean water sources readily available at all times.

What Does “Saturation” Mean When It Comes to Water Sources?

This narrative may be hypothetical, but the situation is a reality for kids all across sub-Saharan Africa.

Water point saturation is critical at The Water Project. We can’t say we’ve done our jobs to help someone affected by water scarcity unless every water source they use is safe and reliable.

In places without municipal water infrastructure, one household must rely on not just one water source, but many. This is the only way to ensure they always have water through dry seasons, drought, hardware breakdowns, and any other incident that might cause a water source to stop working. Unfortunately, installing just one water source per community (or school or health care facility) won’t always address the issues we’re trying to solve.

This disconnect between problem and solution is why The Water Project employs a saturation model when planning where we work next. We aim to saturate, or fully cover, each community we enter with sufficient water sources to create an environment where everyone can flourish.

“The key to understanding the saturation model is remembering that TWP water projects are means to a greater end — improving health and ending the cycle of poverty,” said Emma Kelly, TWP’s Program Manager.

“In order to improve health outcomes, people must always have access to sufficient and safe drinking water. Even a few days of drinking contaminated water can undermine an entire year’s worth of health benefits from accessing a clean source. Once those health benefits are undermined, so are all of the add-on benefits that help lift people out of poverty: dehydrated and tired children are less able to focus in school; people suffering from water-related diseases miss out on income-generating activities; girls and women previously empowered by better health and more free time return to their roles as carriers of water.”

How the Saturation Model Works

Before we can “saturate” a specific region, we first need to know about all its available water resources.

“In order to determine what a community needs to reach saturation, we first need to know what water sources are out there and what kind of shape they are in,” Emma explained. “To do this, TWP and our partner organizations have completed comprehensive water point mapping activities in Western Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Uganda. Mapping also helps TWP choose the most appropriate solution for the community. If there is already a high-yield spring in the target community, for example, spring protection may be more appropriate than drilling a borehole.”

While extremely useful, these mapping activities aren’t easy, and we have had to enlist a lot of help from our partners. Mapping involves dedicated team members driving, walking, interviewing, picture-taking, water-fetching, and entering data. After many months of hard work and time in the field engaging with communities, schools, and healthcare facilities, our partners have mapped over 20,000 water sources. The fruits of this labor are many, and now we enter each community better informed about the area’s water needs and how we can help meet them.

One example of this working well is in Sierra Leone, where we have helped our partner achieve over 85% saturation of the Kaffu Bullom chiefdom (one of our three focus chiefdoms).

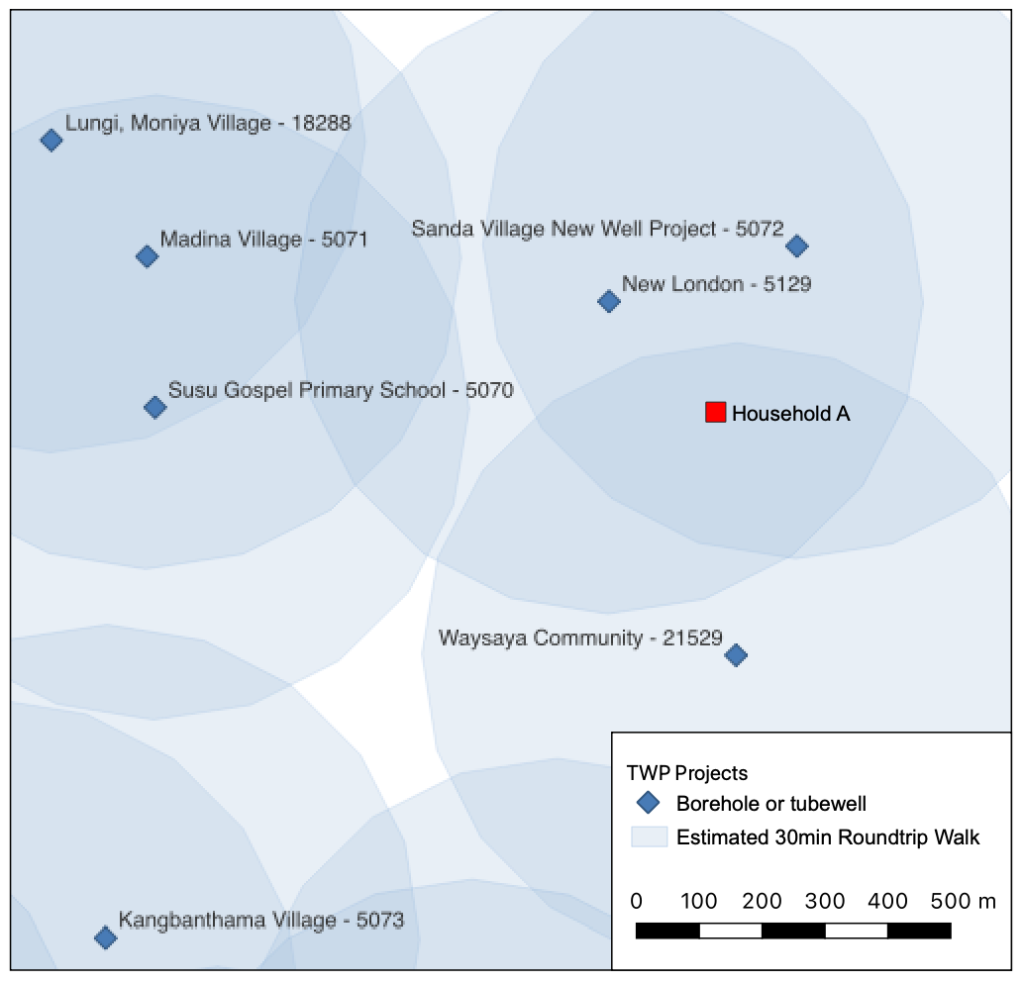

Looking at the above screenshot, we see a saturated area in Kaffu Bullom, Sierra Leone. By our standards, every household must have an improved water source (a source capable of providing safe water) within a 30-minute round-trip walk. We estimate a 30-minute walk to be about 500 meters for the average person walking at normal speed (the screenshot shows these 30-minute estimated radiuses as light blue circles around each water point).

The family living in Household A (the red square) has access to not one but three sources within that 30-minute walk. Even when their nearest source in New London breaks down (because they always do!), the family can access clean water at Sanda Village or Waysaya Community before we rush to repair the New London water source. Family members here never have to revert to a contaminated source.

The children in Household A go to Susu Gospel Primary School (shown in the middle-left of the screenshot). Unlike many children in Sierra Leone, they won’t have to carry their own water or leave lessons to fetch water because the school has its own well. Further, the community members in this area won’t need to depend on the school’s source, potentially depleting the amount available for children during school hours.

Work Yet to Be Done

In our focus sub-counties of Western Kenya, TWP has only achieved 45% coverage. While we’re proud of the work we and our Western Kenya teams have done, we still have so much work left to do.

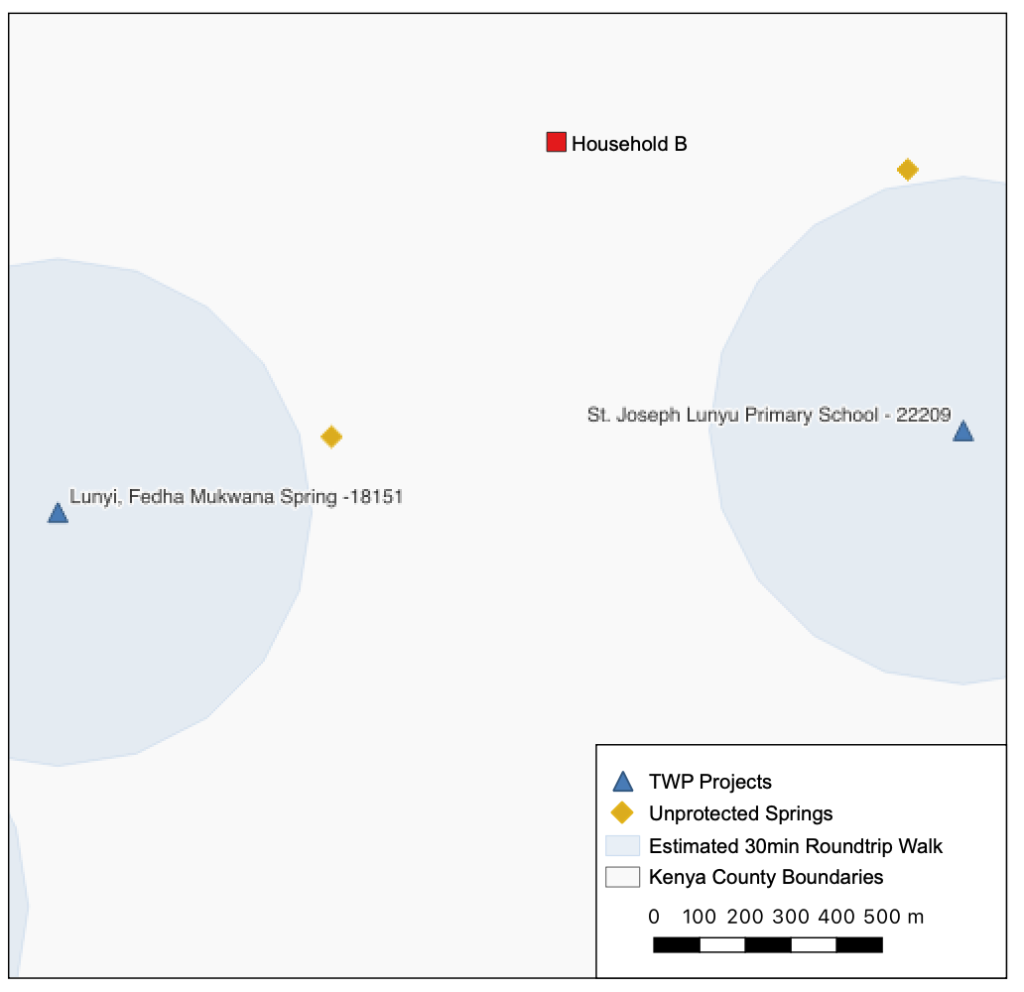

In this screenshot, we see Household B in Malava sub-county of Kenya. You can tell right away that Household B has to make different decisions about water than Household A did. Household B celebrated with the rest of their community when the spring in Lunyi was protected, but they live on the outskirts of the community and still have to walk quite a distance to fetch water.

Even though Household B members know the water from the protected spring is better for their health, it is often crowded when they arrive since it’s the only safe water source in town, and they have to walk farther than others in the community. When Household B runs out of time, they sometimes go to one of the two unprotected springs closer to the house.

The children in Household B attend St. Joseph Lunyu Primary School and luckily don’t have to carry water because the school has its own water source. However, because there are fewer options in town, this source sometimes gets depleted because non-students share the water. When the children leave class to fetch extra water, or it’s their turn to bring water home for the evening chores, they may choose to go to the unprotected spring because they can save time from missing class or getting home.

While they try their best to access clean water, Household B drinks contaminated water sometimes.

Why We Use This Approach

“The reason we’ve moved to saturation is to solve for all three ‘P’s,” Peter said, referring to that “people, places, and puddles” quote from earlier.

Deciding where to implement water projects before we adopted this more systematic approach was heartbreaking — like the trolley dilemma, but in real-time and with real people.

“Before committing to a saturation model, our partners had to spread their limited funding, fuel, time, etc., across large areas and make very difficult decisions about prioritizing the needs of one community over another,” Emma Kelly said.

“Using the saturation model, there is no longer the need for the partner to prioritize one community over another – every single community in our focus area will be covered by the time we leave! When communities within our focus area request a project, partners can confidently say that we’re on our way.

“Furthermore, if they think about the community instead of focusing on the individual water point, they may be able to implement a system of multiple sources with complementary strengths.

“For example, a community may benefit most from a combination of rain-dependent sources and groundwater sources so that the groundwater can be relied on during the dry season. Rain tanks allow storage and rationing but are dependent on seasonal rain. Boreholes are not dependent on rain and may be more reliable in the dry season, but require physical exertion to draw water and typically don’t come with storage potential. A diverse set of source types can give people a variety of useful functionalities and may be more resilient to climate change.”

It took our organization years to cultivate the reach and capacity to tackle an extensive project like mapping. Through the years, we had to develop this holistic knowledge to get to where we are today. We’re proud to say 100% coverage of our service areas is now within our grasp, even as we continue to hone our techniques and learn new things.

To continue this work, we need the generosity of donors who seek to understand the problems of people on the other side of the world. Only with help, and the continued cooperation of thousands of people around the globe, can we inch toward saturation, one water project at a time. Because while we love to see the maps fill up with those blue circles of water coverage, that’s not the end goal. The end goal is to ensure that child in sub-Saharan Africa never has to take another sip of dirty water.

In the upcoming weeks and months, we’ll publish more mapping and coverage information. These numbers show us the measurability of our success while reminding us of the people and stories behind each percentage. We hope you’ll keep reading, learning, and coming along with us on our journey to bring clean water to everyone we can.

Home More Like ThisTweet