What Would John Snow Do? (No, Not That Jon Snow)

Confession: I am a Victorian England history buff. In my co-curricular research, I never thought I’d find something relevant to my real-world job, but here we are. And truly, I shouldn’t be surprised. Water is central to the human experience.

Nowadays, we live in an age of antibiotics and real-time health tracking. It’s easy to forget that one of the most important discoveries in medical history began not in a laboratory, but on a less affluent street in 1850s London: with a map, a water pump, and a doctor willing to challenge everything his peers believed about disease.

The doctor was John Snow. And the pump? It delivered water that Londoners swore by — cool, fresh-tasting, and seemingly clean.

But it was deadly.

Broad Street in the 1850s: The Scene of the Outbreak

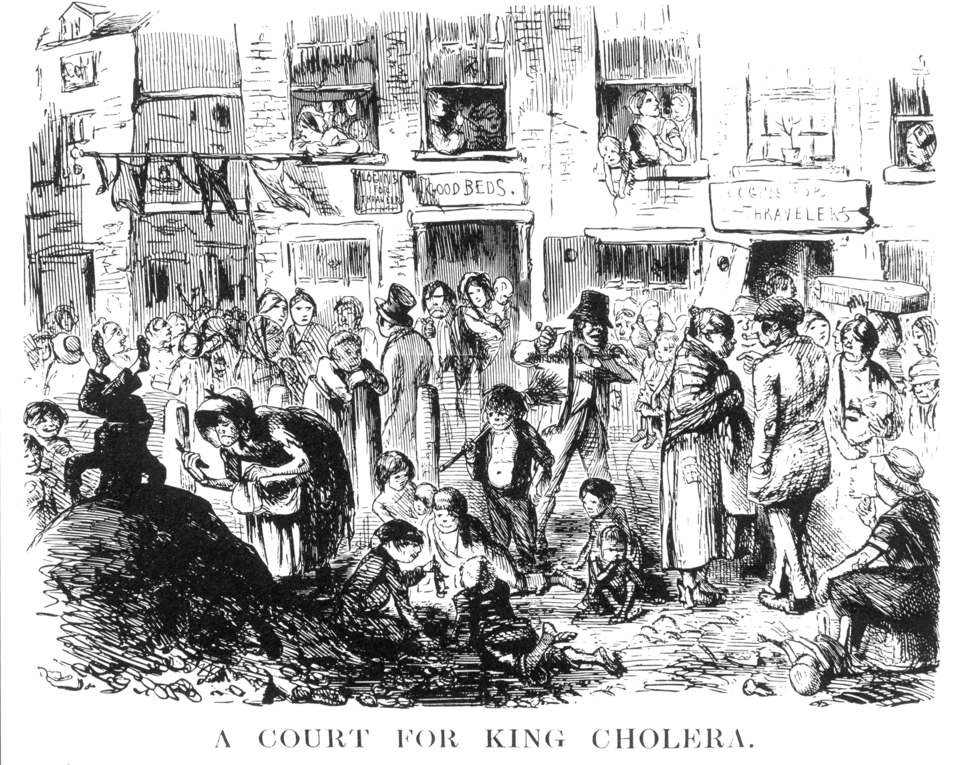

Imagine a narrow, cobbled street, tucked within the dense, working-class neighborhood of Soho. Buildings stood shoulder to shoulder — brick tenements and boarding houses crammed with families, migrants, laborers, and small shopkeepers. Laundry hung from windows. Children played outside, dodging carts and waste.

In 1850s London, there were no sewers or plumbing as we know them today. People emptied their chamber pots into cesspools, or worse, tossed them into the gutters that lined the street. Horse-drawn carts clattered over uneven stones, leaving manure behind. Puddles of standing water mixed with filth. In warm weather, the stench was unbearable — one of the many smells contemporary medical professionals blamed for the spread of disease.

“From inhaling the odour of beef, the butcher’s wife obtains her obesity.”

— Professor H. Booth, writing in “The Builder,” July 1844

The Broad Street water pump was a cast-iron structure topped with a handle, standing in the middle of the pavement. It was a popular gathering point, praised for its “fresh, sweet” water taste. Even as people fell ill around it, many still swore by its quality. Some families would walk past other pumps just to draw water from this one.

Fun fact: you can still visit the Broad Street pump today (though the road is now called Broadwick Street), and perhaps pop across the street to the John Snow pub for a pint.

How did the outbreak start?

At the end of summer in August 1854, people in Soho started dying by the hundreds. It was one of many cholera outbreaks happening all throughout London. While today, cholera is a preventable and treatable waterborne disease, back then, it was neither preventable nor treatable (and estimates say the world still sees between 1.3 to 4 million cases and 21,000 to 143,000 deaths each year).

“The most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in this kingdom is probably that which took place in Broad Street, Golden Square, and the adjoining streets a few weeks ago.” — John Snow, 1854

In fact, most of the afflicted were transported to a hospital to be cared for by famed nurse Florence Nightingale. But even she believed in miasma theory — “bad air” causing disease — and discounted this newfangled germ theory entirely.

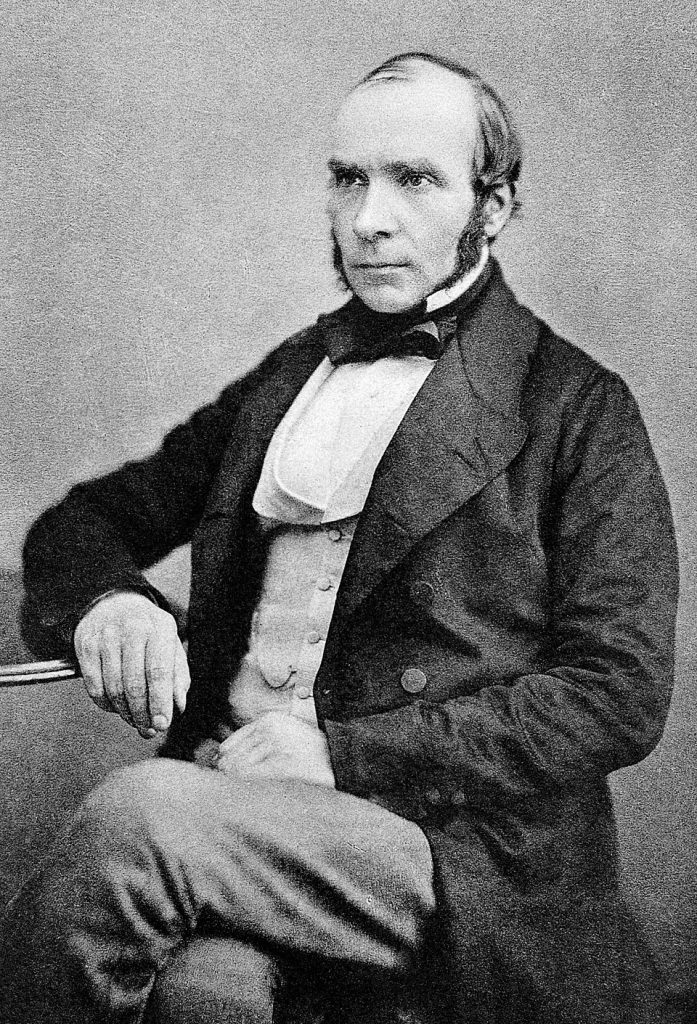

Who Was John Snow?

Although John Snow rose to be a doctor by climbing the ladder of education, he came from humble beginnings. He never fancied himself above the working-class people in Soho.

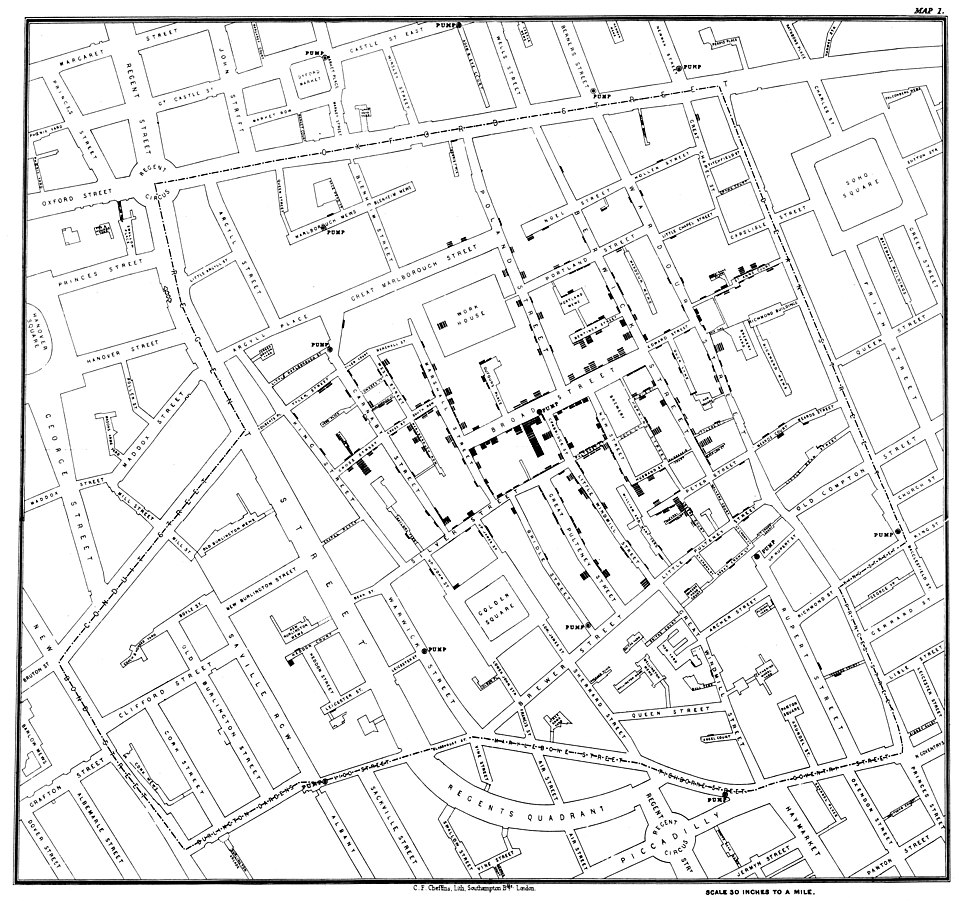

When Snow learned of this deadly outbreak, he tried something radical for his time: he mapped the cases to pinpoint where the outbreak had originated.

Snow was testing a hypothesis he had believed for years. He thought the rapid spread of cholera hadn’t been caused by miasma, but by contaminated water. He noticed a pattern. Every death seemed to trace back to one location: the public water pump on Broad Street.

After collecting testimonies, tabulating deaths, and publishing his now-famous map, Snow persuaded authorities to remove the handle from the pump. Almost immediately, the outbreak stopped.

But like any good scientist (or water, sanitation, and hygiene implementer), Snow questioned the conclusion that his actions had ended the outbreak. Naturally, most of Soho’s inhabitants had fled the area, not knowing the outbreak’s cause — and they had gotten their water from other sources. He pointed to this mass exodus as the reason cholera stopped spreading and killing people.

The medical community and the annals of history remember things differently.

“Dr. Snow recognized that part of treating disease requires viewing patients not as individual, isolated cases, but within the larger environment in which they live.” — American Medical Association’s Journal of Ethics

What happened after the outbreak?

Dr. Snow knew he couldn’t let this horrible disease affect anyone else if he could help it. So, he expanded his research, hoping to prove germ theory to more people. He dubbed this continuation his “grand experiment.”

He traced the origins of water serving several different populations. The households served by one supplier fell ill, while those served by another did not. He learned that the offending company sourced its water from an area of the Thames River polluted with sewage, while the other gathered its water from a (slightly) cleaner area upstream.

Snow became a pioneer of germ theory, expanding humanity’s knowledge about the origins of diseases. Investigating this outbreak became only one of his multiple medical legacies.

How does The Water Project prevent and treat water contamination?

Just like Snow when he removed the pump handle, we at the Water Project aim to prevent cases of water-related diseases before they start.

Before we build any water point, we vet each potential site thoroughly to reduce the risk of contamination. We conduct a sanitary inspection of the water point’s surroundings to identify possible issues, such as nearby latrines or farms using fertilizer. If a risk can be removed or mitigated, we work closely with the community to address it before implementing the project. In cases where contamination risks are immovable or difficult to remediate, we choose an alternative project site.

And also like Snow, we make maps. Water point mapping provides a wealth of data on existing water coverage, areas needing new sources, and opportunities for improving or rehabilitating current sources.

After a water point’s construction, we share the responsibility of keeping it safe in tandem with local water user committees.

We check on each water point once per quarter, with some checks more extensive than others. Some involve calling a water user committee to ask questions, while others involve in-person visits, inspections, and water quality sampling.

Every year, we train our monitoring staff to identify potential issues at each type of water point. For instance, at a borehole well, we’ll ask staff to look for cracks in the well pad, ground erosion around the well, a clean drainage channel, and more.

No system is perfect, but the improved water sources we provide likely prevent countless cases of water-related diseases thanks to our ongoing monitoring and maintenance work.

Why do people drink contaminated water?

Sometimes, even well-meaning people ask this question, and the answer is simple: They have no other option. Asking “why” assumes that the people who drank the Broad Street well’s water were to blame, as are the people still forced to drink from unprotected sources like rivers, springs, ponds, and even puddles across the world today.

Of course, exceptions to this rule exist. For instance, some community members we serve actually prefer the taste of untreated water to the chlorinated alternatives we offer. It’s understandable; chlorine can make water taste different and, for some people, unpleasant. We batch-treat communal sources wherever possible. And while we provide chlorine dispensers at protected springs, we can’t force anyone to use them.

This is why we take things a step further than John Snow was able to during his time. When we install safe water sources, we also educate their water users. Through each hygiene and sanitation training, we help community members understand how to treat their own water using methods like boiling or solar disinfection, especially when they resist chlorine use. But these methods take time, which community members are not always able or willing to spare.

What would John Snow think about our current water crisis?

Removing the Broad Street pump handle didn’t explain exactly how germs worked, and it certainly didn’t cure cholera. But it did stop the outbreak, and it sparked a transformation in how we think about water, sanitation, health, and human behavior.

At The Water Project, we strive to continue his legacy. We map water points. We intervene before danger emerges. And we work with communities to ensure that safe water stays safe — not just today, but for generations.

Of course, I can’t say definitively what John Snow would think, looking at the devastating numbers of people still suffering without access to safe and reliable water.

But personally, I think he would be frustrated. Even 171 years later, humanity still hasn’t found a way to provide safe water access to everyone. Cholera still unnecessarily kills an inordinate number of people each year, despite its preventable and treatable nature. And cholera is only one of many preventable diseases that still plague people who (at least officially) have the right to safe, reliable water and sanitation.

Humans have completely reinvented life for the privileged people of this world since 1854. So, why are these basic needs still unmet for so many?

Who isn’t thinking like John Snow when it comes to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene?

If we’re talking about the Victorian era, I blame ignorance. Medical professionals of the time held onto their outdated beliefs about miasma theory for far too long. They refused to open their minds to emerging science and closed their eyes to deaths and data. Without their voices to shepherd politicians and utility officials into the modern era, it still took several decades for the water and sewer systems in London to improve.

So what prevents everyone from having access to safe water, sanitation, and hygiene today?

Firstly, all infrastructure falls apart eventually. In our work, we plan for this fact every day. When people construct new water sources, they don’t always have long-term sustainability in mind. Almost 15% of newly built water sources fail after one year, and 25% of water points are non-functional by their fourth year.

Secondly, I blame inequality. Some countries presumably can’t afford to supply their citizens with water despite good-faith initiatives. But others fall prey to corruption, with politicians taking for themselves the funds meant to provide basic services to constituents. While this is a complex and nuanced issue, corruption scores shed some light on the ongoing humanitarian issues in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

The third and final reason is the one you can help with: complacency. While many things have changed in the world since 1854, humans still undervalue clean water, even though public water utilities in places like London and around the world struggle to meet safe water needs.

People with piped water — like you and me — should revel in the underappreciated joy of having water at every faucet. Safe water should never be taken for granted; if we forget to care, we might suddenly find ourselves without it. We also need to conserve water wherever we can, because we know exactly what happens when water becomes scarce.

And we need to share the good word about water, far and wide. If you believe that access to safe water is a human right for everyone, like we do, you can convert others by demonstrating your passion.

When you bring safe water to a community, share that you did on social media! Give eGift cards to your loved ones so they can experience the heart-healing glow of helping someone else gain access to water. Start a fundraiser to rally your network. Use your talents to spread the word. And don’t give up, even if progress seems slow. Here at The Water Project, we always “go slow to go fast.”

When John Snow published his findings about the Broad Street pump, he knew he would receive backlash. He knew there were many who would prefer to keep their heads firmly planted in the sand, like Florence Nightingale. And yet, he kept going. He advocated for those without the resources to advocate for themselves. When his first research findings didn’t move the needle, he kept working and campaigning for better water utilities. And when he died of a stroke in his 40s, he was still working hard to convince his fellow doctors of truths he recognized deep in his bones.

Thank you for caring about providing safe and reliable water, sanitation, and hygiene to people in need.

Home More Like ThisTweet