A Special Lady’s First Safari

Teacher/parent note: This blog contains one moment of giraffe romance. It’s brief, but if you’re sharing this story with kids, you may wish to preview that section first!

Day six of my first trip to Kenya began before sunrise. It was time to take a break from long days of field work (visiting communities in need to hear their struggles and communities with water sources to witness their growth). You’ll be hearing about those more in later blogs!

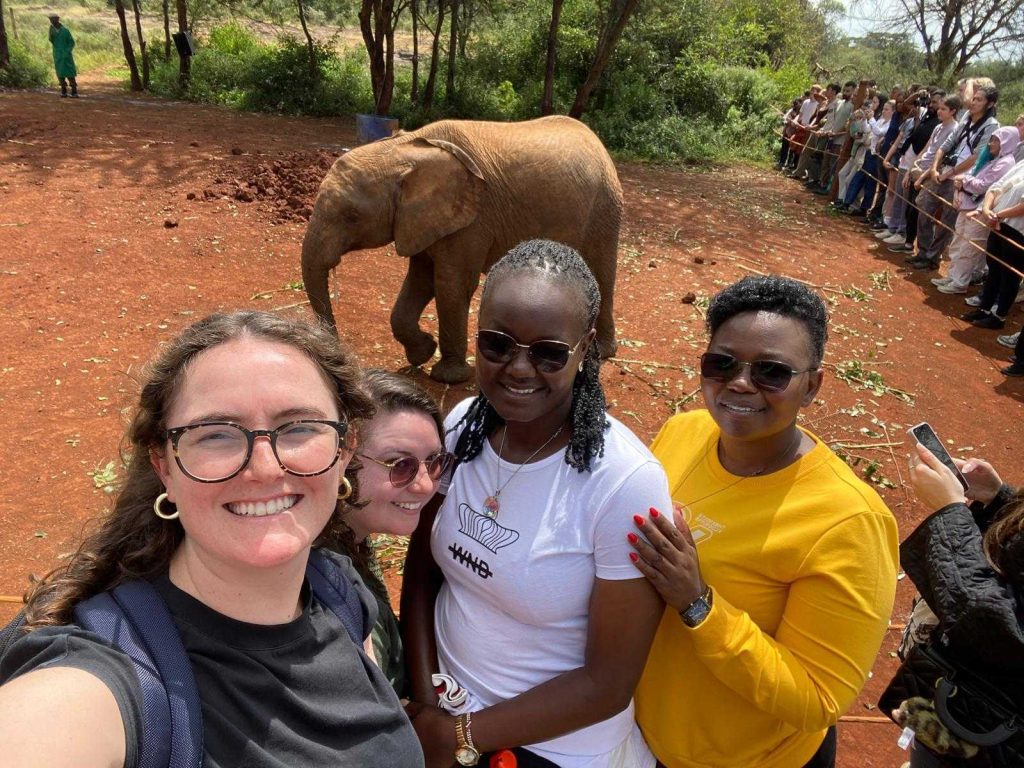

I was traveling with three incredible Water Project team members: Program Manager Emma Kelly, also from the United States, an intrepid traveler and water expert, and our two incredible Impact Communication Officers, Jacklyne Chelagat and Olivia Bomji, both native Kenyans who’d never boarded a plane or been on safari before this trip.

Emma and I had just visited Western Kenya. We were now in Nairobi, where in two days, we would be setting out for Makueni County in Southeast Kenya to visit our work there. But, this day, the safari day, was my most-anticipated day of our visit. You’ll find out why later.

Our hotel in Nairobi afforded us a stunning view of the Nairobi National Park, where we would be headed. It’s kind of astounding that a national park can coexist right beside a national capital thrumming with human activity.

We met our safari tour guide, James, outside our hotel. As we began to drive, he introduced himself as an expert safari guide and a cultural ambassador for the nomadic Maasai tribe. The more James talked, the more I realized we couldn’t have asked for a better tour guide. He explained that the company he works for, Maniago Safaris, doesn’t just do safari tours, but is also actively involved in the park’s conservation efforts.

The first animals we spotted were gathered around a watering hole — two crocodiles and a hippo, who appeared like nothing more than tiny disturbances/lumps on the surface of the water; a group of sacred ibises; and a crane. I was already utterly enchanted.

By this time, the sun was rising over the city of Nairobi, painting the sky in pinks and oranges over the jagged highrise skyline, with wispy clouds casting shadows across the vast green expanse of the national park.

I said to everyone in the car, “This moment is incredible for me. I will remember it for the rest of my life.”

The Kenyans seemed surprised by this (they’re probably used to the beauty of their country), but Emma nodded sagely.

Next, we came upon a huge chubby rhino, whose horns looked absolutely huge in real life. It followed the safari road for a while, and all the jeeps, vans, and trucks carrying safari-watchers shadowed it, bouncing over the impossibly craggy road and driving over the grass and low bushes along its sides.

The smell of the crushed grass was sweet and citrusy, kindly masking the scent of rhino dung (which we were “fortunate” enough to watch being produced fresh!).

We reached a spot in the road where the rains had carved deep rivulets into the golden brown dirt that shook the car and our bones in equal measure.

James said, “Don’t mind the roads. They give you a Kenyan massage. Free — you don’t have to pay.” We laughed sincerely even though I could tell it’s a joke he’s told hundreds of times before.

Over the jeep’s crackly radio, rapid Swahili started up — a lion had been spotted a little farther into the park, and the caravan of spectators sped off in search of it.

As we traveled, we spotted a gaggle of ostriches far away, whose loping gait made us laugh. We scared a few iridescent blue starlings into flight, scattered another flock of speckled brown-and-white birds with comically long legs, and kicked up clouds of dust that James called, “African soap.”

I said, “For us mzungus, it’s self-tanner!”

Finally, we spotted the lone lioness perhaps thirty yards away from the road, crouched in the tall grass, her beautiful head swiveling between the cars, the city, and the park beyond. I lamented my cell phone camera’s insufficient zooming capabilities and coveted the absurdly long camera lens of a photographer in a safari van parked next to our jeep.

I wondered why the lioness was alone. I know from watching many nature documentaries growing up that animals can frequently be rejected from their prides and packs, which inexplicably breaks my heart every time I hear of such an instance. What can be more natural than animal behavior? Why am I empathizing with an animal who may not feel rejection and sadness the same way I do? But I can’t help my silly, squishy heart.

The lioness ducked down into the grass, as if she’d had enough of our human shenanigans, which commenced a mass exodus of safari vehicles. James, being the best safari guide in the world, steered us away from the others so that we were alone. Whenever I could, I stood to peek out the top of the car beneath the lifted roof, but I felt like Kilroy in comparison with the rest of the taller jeep inhabitants, with just my little hands and eyes able to make it over the roof. On the horizon, we saw a long, tall structure, which James explained was a new(ish) elevated railway between Mombasa and Nairobi. It was so long that it spanned the entire span of the Earth’s visible surface, dipping down into nothingness on either side.

“Flat-earthers be damned,” I said to Emma.

“No, they’re right,” Emma replied. “The train just crashes down into the ground on either end of the park.”

“Those poor passengers!” I joked back.

As we watched the train, Emma spotted three lionesses slinking through the bush, so far away that they looked like ants. No other cars were around; the scene was like our little secret.

“They are hunting,” James said. “Can you see their prey?”

We peered through the binoculars for a minute or two, when finally I saw flashes of white, even farther away, close to the train tracks.

“There’s somebody white out there,” I said. “Between those two tall trees, way far off.”

“White?” James said. “White and black, maybe? A zebra?”

“From here, it looks just white,” I said.

He finally saw what I was pointing out, and he said, “Oh! An ostrich. Those are the great big feathers on its wings.”

Emma was absolutely stoked to be witnessing lions on the hunt. “Go get ‘em, girls!”

“Run away, ostrich!” I said.

The animals were already so far off that eventually they became specks and then disappeared. But I have it on good authority that the ostrich escaped its attackers.

Before long, we spotted a group of three zebras munching on grass, flanked on either side by red-necked ostriches strutting around looking important. The sun rays beamed down in stark pale blue stripes, and patchy clouds filtered the light to create a perfect tableau.

“It’s like everyone’s been placed here perfectly for us,” I said.

“God’s creation,” Jackie agreed.

Then, after a while, I gasped. “The lions! They’re here!”

To the right, the same three lionesses we had spotted earlier sneaked through the grass, having apparently given up on the ostrich. The zebra’s ears pricked backward, their tails twitching and swishing. The ostriches carried on strutting, facing the opposite direction, totally oblivious.

“The zebras will warn them of the danger,” James explained. “They speak to each other.”

“Are there any other animals in the park who have a mutually beneficial relationship like that?” I asked him.

“Yes, so many,” he said. “Impalas are good at hearing, while baboons can see very far, particularly when in the trees. Baboons will call out, ‘Oo-ah! Oo-ah!’ when the lions are coming. In turn, baboons eat the dropped fruits from the impala’s feeding.”

By the time we’d finished talking, the lions knew that the zebras were onto them, so they ran off for another chance at a surprise attack later (one we didn’t get to witness — unfortunately for Emma, fortunately for me).

Our next sighting, to our delight, was a giraffe crossing the road ahead of us. A young boy, James told us. He was light in color still, though James explained he will darken as he ages. He chomped on tall leaves and watched us warily.

“Sorry to disturb your breakfast,” I said.

When the giraffe disappeared behind a bush, James drove on, but stopped almost immediately. “More of them, to the left.”

Three giraffes strolled around tall bushes, picking at the choicest leaves and branches. James explained more about the species, where they originate from, how they migrate.

“These are the Maasai giraffes, of my people,” he said. “They are even more prevalent in Masai Mara, the park in my hometown.”

“I love how they walk,” Olivia said. “Like supermodels showing off.”

“When they walk, they walk one foot after the other, like this,” James said. “But when they run, the opposite feet move in tandem to give them more speed. And when they drink, they are vulnerable — they spread their legs out so, so far. In fact, anytime their head is below their heart, it causes problems for them. Their hearts are so big and strong; it takes a lot of energy to get blood all the way to their heads.”

We each took selfies with the giraffes in the background since they didn’t seem bothered by our presence.

But of course, more safari vehicles found us and spoiled the peace of the moment, and James drove us onward.

After a few minutes, James and Emma both exclaimed. An impala had darted across the road ahead, but disappeared quickly into the bush.

“Where there is one, there are usually more,” James said. “We will see.”

Sure enough, when we pulled forward, three impalas were snacking on leaves and fruits.

“They have horns, so they are the males,” James said.

“That one has a broken horn,” Emma observed.

“Yes, that one is an old man,” James said. “He has seen many things. You see his coloring?”

Next, we happened upon a flock of many different species of birds all gathered on the sides of the road. More starlings, the long-legged ones, and a tall black-headed heron, which looked so similar to the great blue herons I’m used to seeing on the lakes in New Hampshire, and apparently they have similar habits and habitats. It felt like seeing an unexpectedly familiar face in Kenya!

Farther down the road (or in another direction — James knew exactly which roads to take, and I couldn’t tell where we had been or where we were going), we saw a whole herd of zebras — maybe twenty or thirty of them. Jackie took a video of them eating, and we sat and watched them for a while, marveling at the quiet of the park, only interrupted by birdsong.

By this time, we were close to the elephant orphanage, which was the moment I had most looked forward to during this Kenya trip. But just as we had given up on seeing anything else before we reached the entrance, we saw dozens of giraffes grouped together.

“This is crazy,” James said. “You never see so many animals in one day. Never. You girls are very lucky. Very blessed.”

We all agreed that we were as we admired the giraffes. One even loped down the safari road, slowing an oncoming jeep to a crawl as it meandered along without a care in the world.

“This one is very old,” James said, pointing out another giraffe on the left. “She has white hair.”

“Hello, grandma!” Jackie called out.

“Yes, indeed!” James laughed.

“Shikamoo!” I said (which is the Swahili greeting for respecting your elders).

Then, a funny thing happened. Two giraffes were kind of circling each other about fifteen or twenty yards away from the car.

“It is mating season,” James said. “He is pursuing her, but she isn’t sure of him yet. You see, he is begging her. ‘Please, please!’ All us men, we do this, we beg.”

Then the female stopped her dance, having made her decision.

“Oh, it’s…it’s happening?” I asked.

“Yes, it is happening,” James said. “You girls, you are very lucky. She is letting him.”

I couldn’t take my eyes off the two giraffes.

“It is very quick, like that,” James said. “Just once, and he is done.”

Jackie, Olivia, Emma, and I exchanged knowing smiles, but we didn’t make any comments.

“Oh, a baboon just crossed the road up there,” James said, driving forward. “Did you see it?”

We hadn’t, unfortunately, but it was good to have a distraction at that moment. So, we drove forward to the entrance of the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, and I was rubbing my hands together in excitement. I have always loved elephants — how smart and wise and full of personality they are. I couldn’t wait to see the calves. James even said we could touch them.

As we waited in the line of cars sitting at the front gate, James said, “I will show you something.” He hopped out of the car, took a sharp rock, and drew a diagram in the dirt. “The elephant feeding area, it is a rectangle, like this. Most people, they will go to the left or the front. They will crowd around, and you will not be able to see. But you girls, you must go right. Not all the way here on the side, but right here.” He drew an X. “They will come out and come up to the rope, and you will touch them.”

We thanked him for the insider info as he exchanged words with a guard, whom he seemed to know well, and received our tickets. We parked and joined the throngs of people headed toward another closed gate.

“Ah, today is a very good day,” James said. “Not many people. Not too bad.”

To me, it looked like a lot of people. But of course, he is the expert, and I was grateful to be there on a Saturday and not have our experience ruined by even more people jockeying for the best views and spots.

James escorted us inside, leading us to the exact spot he had indicated as if he hadn’t already drawn us a diagram. “Right here is perfect. You will enjoy!”

We thanked him again, and he went back to wait at the car. It was some minutes before the keepers arrived, lugging a wheelbarrow full of giant baby bottles full of what turned out to be human baby formula (cow’s milk has too much fat, apparently), and then a few more minutes before someone cried out and pointed through the line of trees at the far end of the feeding area.

Flashes of brown-skinned babies, their ears flapping with every step, shone through the foliage. Then, they burst into the clearing in groups of two and three, heading straight for the branches strewn around the clearing at the edges near the ropes with their bunches of excited people. Most of the elephants were of a similar size, maybe six to seven feet tall. One was taller, maybe eight feet tall. And one, who was wearing a blue blanket over its back, was teeny-tiny, barely three feet tall.

The elephants felt around in the dirt for the branches with their wrinkly trunks, the front and back grasping together like stunted little fingers until they wrapped around the wood to bring it up to their mouths. Some did it daintily, one branch at a time, finishing chewing completely before feeling around for the next. The elephant nearest us, though, was “greedy” (as Emma pointed out), shoving branch after branch into its mouth as if it couldn’t chew or eat fast enough.

A speaker crackled to life, and one of the keepers started to speak. He asked for total silence so that the elephants would feel comfortable and stay close to the ropes. I found it easy to follow this directive, awe-stricken as I was, but people are people, and they grew louder and louder as the hour-long presentation took its course. I kept wishing he would scold them for speaking and laughing and exclaiming, but I guess if you scold the visitors, they are less likely to become donors.

The elephants ate, farted, peed, pooped, stuck their butts directly in people’s faces, blew bubbles in the little watering hole, drank from a water trough, bumped into each other, poked the keepers with their trunks, slung mud onto their backs (and onto the onlookers!) to stay cool, and wallowed in the moist dirt until they were slick and shiny with mud.

Only one came close enough for me to feel, and the texture of their skin and hair was like nothing I’ve ever felt before. The skin was so rough, almost like sandpaper, with deep creases that allow the mud to cool them for longer stretches. They had a head of hair almost like humans’, but more sparse, and also spread all over their bodies and legs. The hair was wiry and stood straight up, unyielding to my hands. I was gentle as I stroked the side and back of the elephant, looking at its long-lashed eye to make sure I wasn’t bothering it. But apparently, this was the wrong tactic, because a man to our right scratched and slapped an elephant’s side with a lot of brute force, and the elephant backed right up into the rope as if telling him to keep going.

As all this was going on, the keeper introduced each elephant in turn, though keeping track of their names and which elephant he was speaking about was impossible with all the people talking over him. But I still caught pieces of their stories — separated by human-elephant conflict, abandoned due to a lack of resources (the most prominent of which, unsurprisingly, was water), caught in a poacher’s trap, stuck in ditches and wells, struck with a poisoned poacher’s arrow, found in distress next to a dying mother. My heart broke over and over.

The keeper said that they have always been successful in reintegrating the 380-something elephants the Trust has harbored since its inception in 1977; not one has stayed, though each elephant decides on its own when it leaves for good. When they bring the animals into the wild, they call its name for it to come to bed each night. One day, the elephant won’t come to the keepers’ call. When he said this, I felt so sad — I couldn’t imagine being a keeper and saying farewell to a longtime friend like that. But the speaker said when it happens, they feel great, because they know they have done their jobs well. They never allow an elephant to be with the same keeper for too much time, or it will become attached and not want to go back to nature. That’s the way it should be done, of course. But for that reason (and because the keepers sleep on the floor with the babies throughout the night to feed them every three hours), I’m glad I’m not an elephant keeper.

The speaker said that what we’ve heard is true — elephants have excellent memories. So excellent that, when significant events happen in their lives, they will return to the Trust. When they are sick or injured. When they find their mate. When they have babies. And even just to show off new friends. When I heard this, I cried, just like I had warned Emma, Jackie, and Olivia I would. But thankfully, I don’t think anyone saw me. It just touched my heart so much to hear that the elephants trusted their humans despite all the terrible things humans continue to do to elephants and wildlife. They know that not all humans are the same.

In fact, when the keeper opened up the presentation for questions, I raised my hand and asked what elephants think about humans. For some reason, a lot of people chuckled at this. But the keeper had made eye contact with me a lot during the presentation, probably because I was so intent on his words and nodding along with everything he said, and he seemed to understand. He said, “Elephants are smart. They are like us. They can read your heart and tell whether you have good intentions toward them.”

All too soon, the presentation was over; the elephants went back to their pens, and we were all funneled to the gift shop, where I bought a t-shirt that ended up being far too small (Kenyan clothing sizes are not the same as American ones — it’s now a present for my husband) and a pack of notecards, with which I wrote farewell letters to Emma, Jackie, and Olivia.

From there, we went to lunch. Instead of going to the usual restaurant that was listed on our itinerary, James said, “You are very special ladies. I would like to take you to Matbronze instead of the museum. It isn’t far, and you will like it. There will be fewer people there. Everyone will go to the museum, but at Matbronze, it will be peaceful.”

We agreed, because he hadn’t steered us wrong yet, and he called ahead to get us the best seats in the house. “These are very special ladies,” he repeated to the person on the phone. “Give us your best umbrella, please. They are very tired from the safari and need to eat.”

He took us to Matbronze, which is owned by a “very kind, very professional” (according to James) woman. It’s both a beautiful art gallery and a restaurant.

James treated us to a delicious lunch while I admired all the exotic plants surrounding us in a beautiful garden. I’d never seen any of them before in my life, and I know my plant-loving husband would have absolutely loved being there. However, I couldn’t take any photos since my phone was covered in elephant residue from my elephant-touching escapades.

James liked hearing about our work, and it turned out he’s something of a philanthropist himself. He worked together with others in his home community to start a school for local kids. He facilitated the sourcing of their own water project and even got money from the government to get it solarized piped water. It started out with just 20 kids, but now they’re up to 400-something pupils. We all lamented the state of politics in our countries, too. He said he’d had the opportunity to be the chairman of his community, but told his friend to take the opportunity since he thought his friend could do it better. He also seemed to know everyone at Matbronze, and all the guards at all the park entrances. They called out to him and shook his hand over and over. But even people he didn’t know, he greeted warmly and spoke easily with.

After lunch, we headed to the Giraffe Centre (which is right next door to the world-famous giraffe hotel). Again, James was incredible. He followed us inside the park, found a guide, and told her: “Take very good care of them. They are —” you guessed it! “— special ladies.”

We were very lucky to have the guide, and she was so kind. She rattled off facts about the giraffes as she called out to them by name and shook a feeding bowl to get their attention and have them come to us.

As we held out little pellets of feed for them to slimily lick out of our fingers, the guide told us their names and personalities. Most of the giraffes come to be rehabilitated and then go back to the wild. But one giraffe, Kelly, is the old man of the group, who was born at the sanctuary and refuses to leave. He watches over the rest of the rotating herd and keeps them in line. Beneath the giraffes’ feet, warthogs scrambled to lap up dropped food pellets, dropping down on their little knees to reach them.

“Watch out for this one,” she said, as one giraffe approached. “She likes to headbutt visitors sometimes.”

At one point, a giraffe accidentally stepped on a warthog it hadn’t noticed in its excitement over licking the feed out of my hand. The warthog squealed and frightened the giraffe, and all the animals scattered. The guide had to coax them back over to us, but this had spooked Jackie and Olivia away from feeding the giraffes, and Emma said she didn’t like the slimy feeling of their tongues, so I took the rest of their feed and giggled like a little girl as I fed them over and over until I noticed the others had retreated to the shade and were looking very tired.

We thanked the guide and tipped her and then rejoined James. He had just picked up some luggage for a few other clients at his boss’s request. He said, “I can’t believe how much these fools packed. Can you believe it? Giant luggages like these ones. When you go somewhere, you take a little bag, not much. But this, eh? How much stuff could you possibly need?”

Emma, Jackie, and Olivia all looked at me, who packed a giant bag so heavy that it’s hard for even the strong men of the Western Kenya staff to lift and carry.

“Yeah, who would pack like that?” I asked, then hid my face toward the window.

The girls all laughed heartily at my shame.

We returned to the hotel, and everyone went their separate ways to rest, as it had been an early start and a long day.

I turned on the TV to find a National Geographic documentary about elephants in Kenya playing. Now, I’m not spiritual or religious, but sometimes things just feel like fate.

Watching the film reminded me to visit the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust website and “adopt” an elephant. I picked Epiya, who had been fondly labeled “the naughtiest girl” by the keeper at the Trust. I liked the idea of fostering her escapades.

The next documentary on my TV was about Ethiopian wolves, who look like big American foxes. In it, a female pack leader had grown her pack from nothing after a drought had wiped most of her family out when she was very young. Now, they were growing too populous, and the matriarch knew the resources in their area were too few.

“She will have to make a tough decision,” the narrator said. “It is time for her firstborn daughter, with whom she has a great relationship, to go off and start her own pack in a new area with more resources.”

The matriarch was in the process of rejecting the affection/grooming of her daughter, growling and snarling at her, when I turned the TV off, thinking of that lone lioness I’d seen that morning. I decided it was enough heartbreak for one day.

It was the best of days, one I will remember forever and ever. But it was another day on this Kenya trip where I was reminded of the dangers of having an open heart, and of living with an overactive empathy muscle. It’s a constant struggle for me — some days I add bricks to the walls around my heart to protect it, and other days I demolish the walls and leave my heart raw and aching.

I’m reminding myself that the day I stop challenging myself is the day I stop growing.

Home More Like ThisTweet