For the 175 people of Mukangu, the sky determines how and when they fetch water.

In the dry season, several water sources in surrounding communities dry up, which sends flocks of people to Ibrahim Werabukaya Spring to fill their jerrycans, crowding out the locals.

"Community members inform us that the water crisis worsens during the dry season when people from far and wide have to come and fetch water," said our field officer, Lillian. "This is when carts will be seen having dozens of jerrycans and motorcycles will be heard at the water point ferrying water. This causes the community members to wake up so early in the morning to fetch water to avoid queueing up with those who come from far [away]. [Also] during the dry season, the hand pump well in the nearby primary school goes dry, leaving the pupils to wander in the village in search of water."

But still, this might be preferable to the wet season when the steep, rocky terrain surrounding the spring becomes slick with water and mud.

"I have broken three buckets at this water point by sliding and falling," said 17-year-old Maureen (shown filling her jerrycan above). "My mum would not hear of it when I broke the third bucket, and she gave me a thorough beating since it costs her to buy a new one. The last incident happened two months ago when we were experiencing a heavy downpour, and the terrain was [very] slippery."

The spring construction itself was installed so long ago that no one living can say when it happened. Water seeps through the cement surrounding the discharge pipes, slowing the flow of water from the pipes themselves to a trickle. With water escaping around the construction, much of it pools around the community members' feet when they fetch water instead of draining away as it should.

"The water from this water point is not safe for drinking," Lillian explained. "Several contamination channels can be seen, from the dirty water mixing with the semi-protected water, to the community members touching the fetched water with dirty hands that have touched the ground in search of balance when leaving the spring due to the poor terrain."

"Like six months ago, I had diarrhea for two days," said Andrew Werabukaya (shown above fetching water). "I went to Chombeli Health Center, which happens to be our nearest. The doctor informed me that the infection was caused by the consumption of dirty water, and I automatically knew it was the water that I consumed from this unprotected spring."

Although there is another spring in Mukangu that was protected in 2021, it is not only far away from people on this side of the village, but it is always crowded, no matter the season. So every day, community members make a choice: to waste time walking to and waiting for safe water, or to risk their health on a more convenient water source.

“Households with travel times greater than 30 minutes have been shown to collect progressively less water. Limited water availability may also reduce the amount of water that is used for hygiene in the household.” (The Relationship between Distance to Water Source and Moderate-to-Severe Diarrhea in the Global Enterics Multi-Center Study in Kenya, 2008–2011) - American Journal of Tropical Science and Medicine

The people on this side of Mukangu need a safely accessible water source closer to home.

What We Can Do:

Spring Protection

Protecting the spring will help provide access to cleaner and safer water and reduce the time people have to spend to fetch it. Construction will keep surface runoff and other contaminants out of the water. With the community’s high involvement in the process, there should be a good sense of responsibility and ownership for the new clean water source.

Fetching water is a task predominantly carried out by women and young girls. Protecting the spring and offering training and support will, therefore, help empower the female members of the community by freeing up more of their time and energy to engage and invest in income-generating activities and their education.

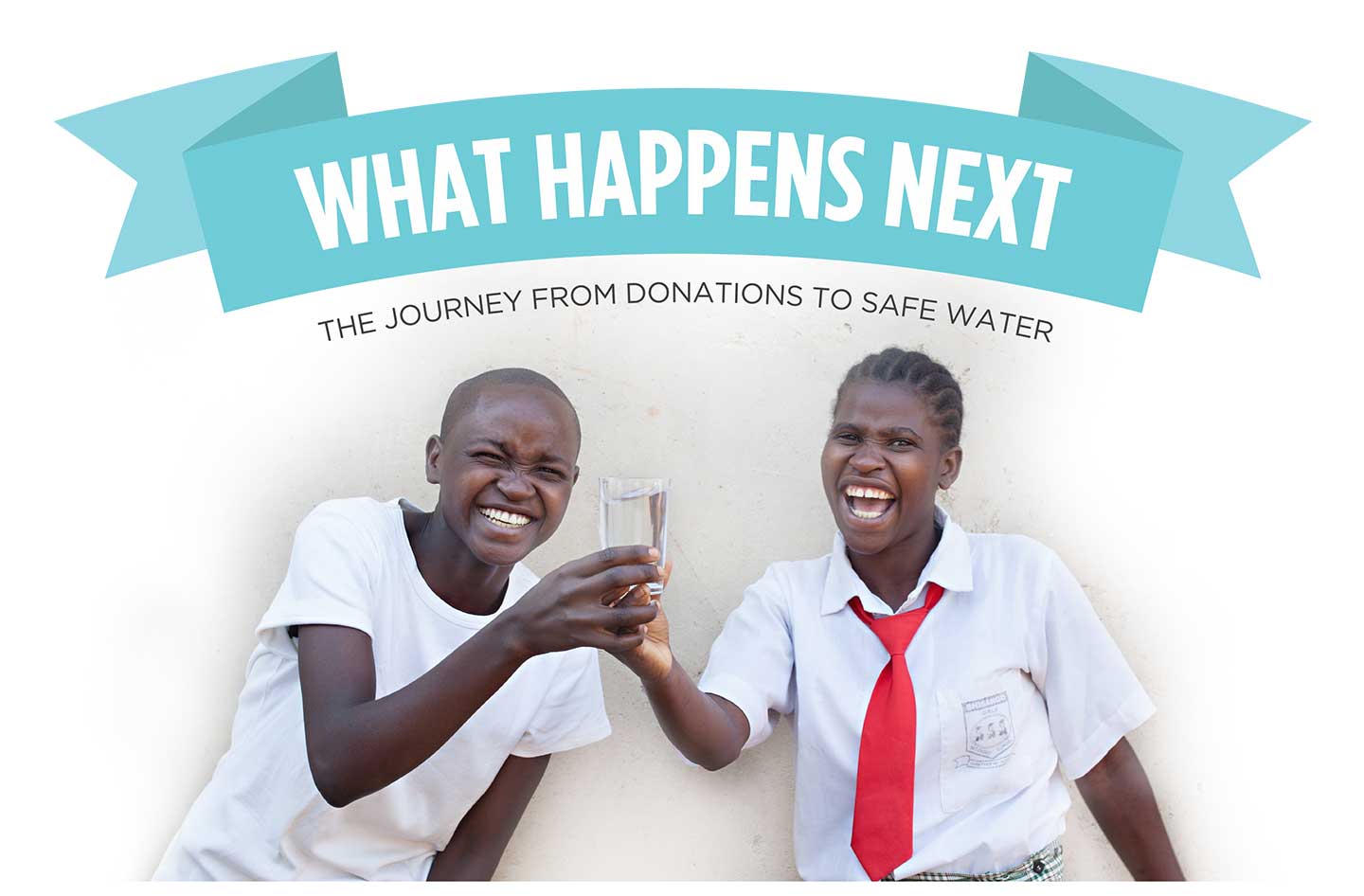

Training on Health, Hygiene and More

To hold training, we work closely with both community leaders and the local government. We ask community leaders to invite a select yet representative group of people to attend training who will then act as ambassadors to the rest of the community to share what they learn.

The training will focus on improved hygiene, health, and sanitation habits in this community. With the community’s input, we will identify key leverage points where they can alter their practices at the personal, household, and community levels to affect change. This training will help to ensure participants have the knowledge they need about healthy practices and their importance to make the most of their water point as soon as water is flowing.

Our team of facilitators will use a variety of methods to train community members. Some of these methods include participatory hygiene and sanitation transformation, asset-based community development, group discussions, handouts, and demonstrations at the spring.

One of the most important issues we plan to cover is the handling, storage, and treatment of water. Having a clean water source will be extremely helpful, but it is useless if water gets contaminated by the time it is consumed. We and the community strongly believe that all of these components will work together to improve living standards here, which will help to unlock the potential for these community members to live better, healthier lives.

We will then conduct a small series of follow-up trainings before transitioning to our regularly scheduled support visits throughout the year.

Training will result in the formation of a water user committee, elected by their peers, that will oversee the operations and maintenance of the spring. The committee will enforce proper behavior around the spring and delegate tasks that will help preserve the site, such as building a fence and digging proper drainage channels. The fence will keep out destructive animals and unwanted waste, and the drainage will keep the area’s mosquito population at a minimum.

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project