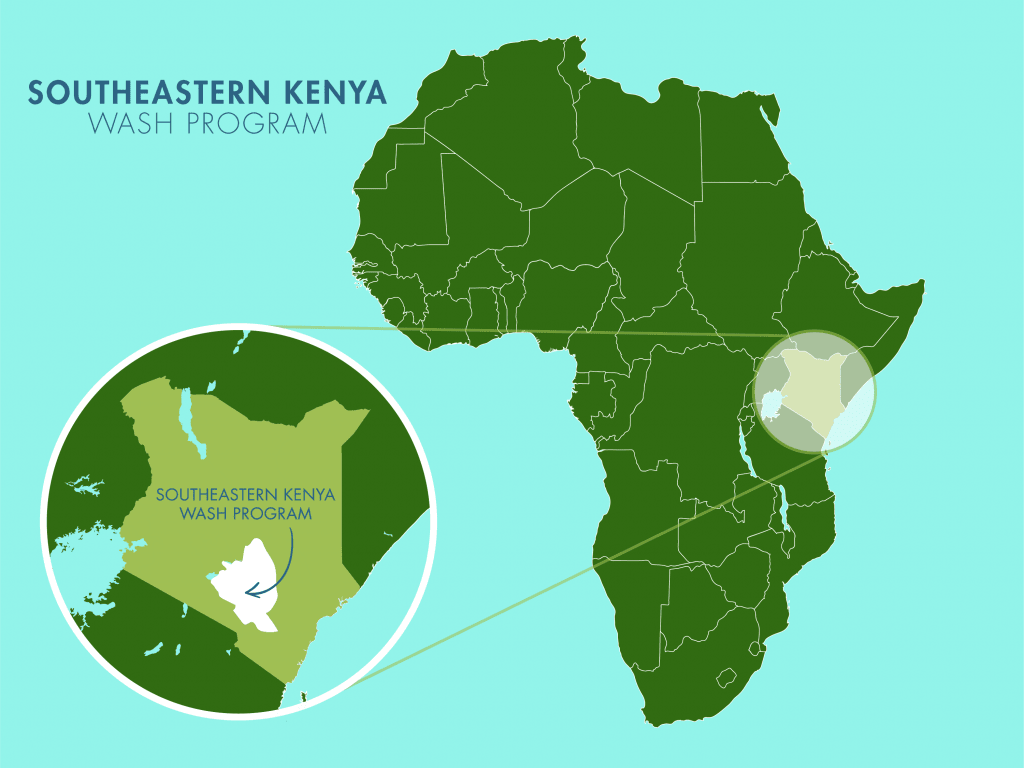

The Nzuli Secondary School is situated in a semi-arid region, where dust, rock, and marram (coarse grass) roads are part of everyday life. Since its founding in 2004, when parents and local leaders came together to buy land and construct the first classrooms, latrines, and dormitories, the school has continued to grow. Today, it serves 305 students—139 girls and 166 boys—with 152 day scholars and 153 boarders, supported by a dedicated team of 25 staff members.

Students wait in line for water from the rainwater harvesting tank on campus.

Despite the harsh climate and the challenges of water scarcity, Nzuli Secondary is a place of ambition. The grounds are busy with students moving between lessons, teachers balancing heavy workloads, and dreams that stretch well beyond the school gates. But beneath this energy lies a constant logistical and emotional puzzle: how to secure enough safe water for everyone, every day. As Teacher Kevin Wesonga says, "It is incredibly disheartening."

The school currently depends on two main water sources: plastic rainwater tanks and a tap stand connected to a community borehole. On paper, both sound promising. In reality, they come with limitations that the school has learned to work around with resilience and creativity.

At the rainwater tanks, students often have to wait in line, as over 300 people rely on them for their water needs. The tanks are small, and the rains are unreliable, so in dry periods, they sometimes run low or completely dry.

The tap stand tells a similar story. It is about a 20-minute round-trip from school, with queues that can steal even more of their school day. It is piped from a community borehole that serves both the school and surrounding households. During long dry spells, demand surges, the water level drops, and at times the source runs dry. Pipes are prone to damage from heat and corrosion, and repairs can be costly and time-consuming. The water has a saline taste and is often rationed.

Yet, despite these hurdles, the school perseveres and technically goes on, but every day is a constant struggle.

Water here is not only scarce but also expensive. The school spends approximately Ksh 21,000 (approximately $160 USD) every month on piped water from the tap stand. That is money the administration would rather invest in classrooms, dormitories, books, lab equipment, and additional teachers—but for now, water has to come first.

Teacher Kelvin Wesonga, one of Nzuli’s 25 staff members, sees these trade-offs up close. As a teacher and mentor, he is deeply involved in both his students’ academic progress and their well-being.

Teacher Kelvin Wesonga.

When asked about the impact of water costs, he explains: “Spending over Ksh 21,000 monthly on water drastically affects our school’s ability to invest in learning resources, infrastructure, and student welfare programs. The money that could improve education and the school environment is instead going to sustain an unreliable and unsafe water supply.”

Kelvin also imagines a different future if the school were freed from this burden: “Those funds could be redirected toward building much-needed dormitories, improving sanitation facilities, buying books as well as lab equipment, hiring more teachers, or starting sustainable agriculture projects that support both learning and nutrition.”

These are not wishful thoughts; they are practical ideas from someone who understands both the students’ needs and the school’s potential.

To make Kelvin's role even trickier, water here is not always safe. Currently, the water at Nzuli is not consistently treated, which leaves students and staff vulnerable to water-related illnesses, such as amoebiasis and dysentery. This is not just a health issue—it’s an academic and emotional one.

Kelvin recalls a recent incident: “Recently, some of our students developed severe stomach pains and diarrhea after consuming water from the tap stand. It was distressing to see them suffer, and their parents had to be called to take them for medication, missing several days of class. Sadly, this isn’t an isolated incident—it has happened to several students and even staff in the past.”

He sees the consequences in his classroom as well: “Water-related illnesses result in absenteeism, reduced concentration in class, and added healthcare costs for already struggling families. Students fall behind in their studies and sometimes never fully catch up. It also places an emotional burden on teachers who are forced to watch learners suffer due to a basic need not being met.”

For Kelvin, the issue goes beyond inconvenience: “It is incredibly disheartening. As a teacher, I would want to see my students thrive, but it’s painful to know that the water they rely on—a necessity of life—is putting their well-being at risk. It’s unfair and avoidable, and we desperately need a sustainable solution.”

The scarcity of water also affects daily routines in subtle but important ways. Students are constantly encouraged to conserve, which, as Kelvin notes, “compromises hygiene.”

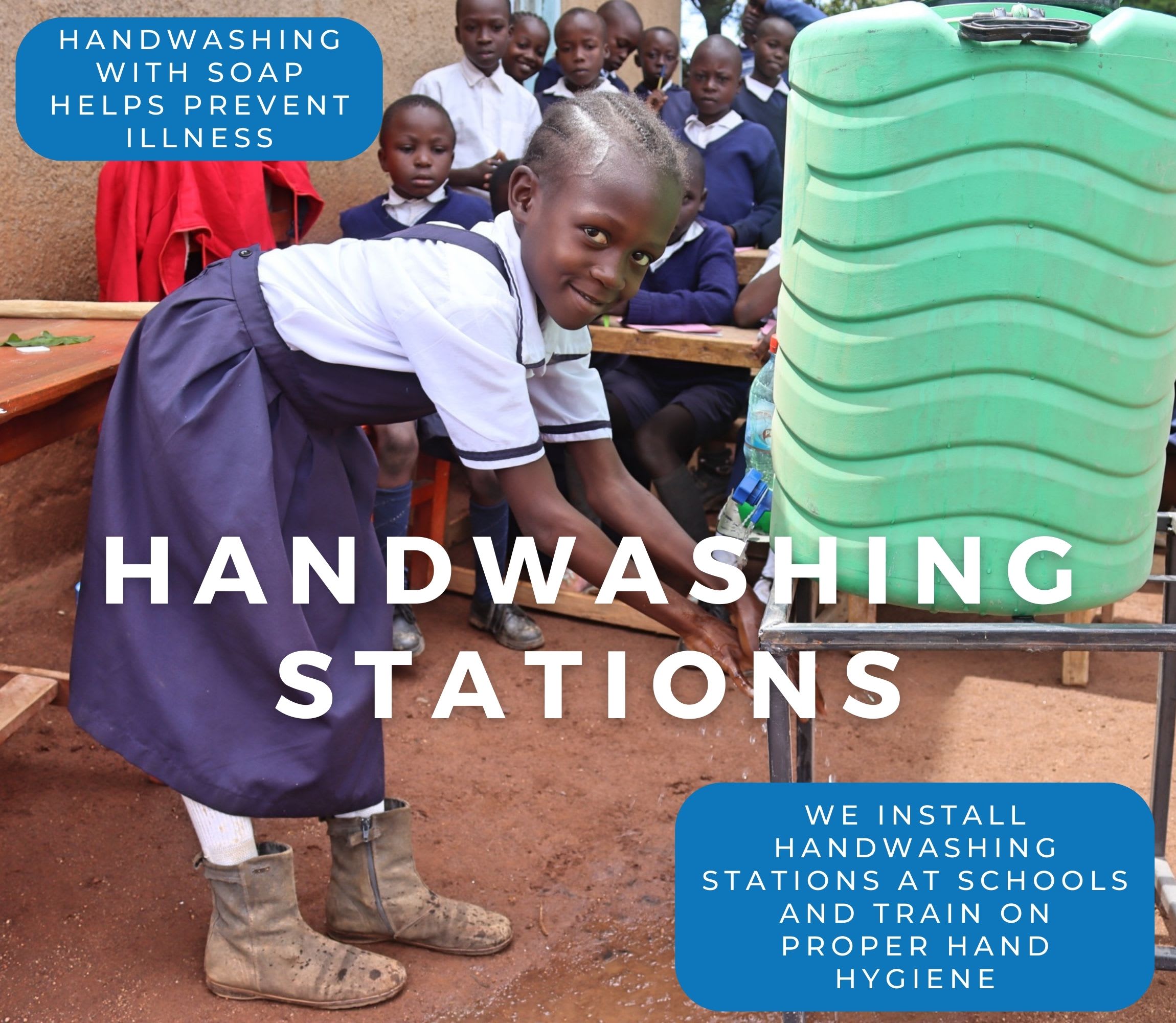

Handwashing stations that are a challenge to fill.

“They are constantly under pressure to conserve water, which compromises hygiene. They often cannot wash their hands, clean classrooms, or have water to drink on hot days. It affects their dignity, health, and their ability to concentrate in class," Kelvin continued.

Teachers, too, are stretched by having to manage limited water:

“Rationing creates tension. We often have to make tough choices—whether to allocate water for cooking, cleaning, or drinking. There are complaints from students, and managing these expectations without enough water is stressful and time-consuming for staff," he said.

Even so, the staff and students at Nzuli do not give up.

During visits to Nzuli, Field Officer Alex Koech listened closely to the experiences of teachers and students.

One moment stayed with him in particular: “One of my striking moments was my conversation with Kelvin, who recalled a recent case where students fell ill from drinking untreated water sourced from a vendor. He described how the illness not only disrupted the student's studies but also weighed heavily on staff, who constantly face the dilemma of choosing between rationing water and keeping students healthy. His concern wasn’t just professional—it was personal. It reminded me that educators here aren't just instructors; they are caretakers navigating difficult trade-offs every day.”

Collecting from the rainwater harvesting tank.

Alex’s reflection highlights a powerful truth: Nzuli’s teachers are not passive observers in this crisis. They are problem-solvers, caregivers, and advocates for their students’ futures.

The school has clear development goals: building more dormitories, improving hygiene and sanitation facilities, enhancing academic performance, increasing enrollment, and establishing a school agriculture farm for practical learning and nutritional support.

Reliable water is at the heart of all these plans.

Current school buildings.

Kelvin is confident that access to safe, dependable water would have a direct impact on learning: “With safe and reliable water, students would be healthier and more consistent in their school attendance. Improved hygiene and sanitation would lead to fewer illnesses. More time would be available for studying instead of worrying about water, which would certainly boost academic performance.”

To address these challenges, the community, school administration, and partners have proposed a 104,000-litre masonry rainwater tank within the school compound. Unlike the current small plastic tanks, this masonry tank would be large, durable, and better suited to the harsh sun and erratic rains.

By harvesting and storing enough rainwater during the wet season, the tank would help carry the school through dry periods, reducing dependence on the saline, unreliable borehole.

Most importantly, it would provide safer, cleaner water—supporting health, dignity, and learning.

Kelvin captures what water really means here: “Water is more than life for me or us here in school. The availability of adequate water in our school means a comfortable learning space for the teachers and students. It means a better opportunity to achieve a better tomorrow for the learners. It also means growth for the school and community at large.”

The proposed 104,000-litre masonry tank is more than infrastructure. It is a tool in the hands of a determined school community—a community that has already proven its ability to turn limited resources into real progress.

With reliable, safe water, Nzuli Secondary’s students and teachers will not be rescued; they will simply be better equipped to do what they are already doing: building a stronger, healthier, more hopeful future for themselves and their community.

Steps Toward a Solution

Schools without reliable, on-premises water access often rely on students to fetch and carry water, leading to rationing and uncertainty about water quality. The water is typically poured into a communal storage tank and used by the entire school. With children carrying water from all different sources, it is also impossible for teachers and staff to know exactly where the water comes from and how safe it is to drink.

A new water point will be located on-premises at the school to ensure accessibility, reliability, and safety for students, teachers, and staff while meeting our school coverage goals. Having water available at the school allows children to drink, wash hands, and use sanitation facilities without leaving school grounds, preventing disruptions to lessons and reducing safety risks. A dedicated source increases water availability, reduces reliance on stored water, minimizes rationing, and ensures confidence in the safety of the water. This means staff and students are healthier, and their lessons aren’t disrupted, contributing to a better education!

Our technical experts worked with the school leadership and the local community to identify the most effective solution to their water crisis. Together, they decided to construct a rainwater harvesting system.

Rainwater Harvesting System

A rainwater collection system consists of gutters that channel rainwater effectively into large holding tanks. Attached to buildings with clean, suitable roofing, these systems are sized according to the population and rainfall patterns. Water can be stored for months, allowing for easy treatment and access. Learn more

Handwashing Stations

Alongside each water source, we install two gravity-fed handwashing stations, enabling everyone at the school to wash their hands. Handwashing is crucial for preventing water-related illnesses within the school and community. Student “health clubs” maintain the stations, fill them with water, and supply them with soap, which we often teach them how to make.

School Education & Ownership

Hygiene and sanitation training are integral to our water projects. Training is tailored to each school's specific needs and includes key topics such as proper water handling, improved hygiene practices, disease transmission prevention, and care of the new water point.

To ensure a lasting impact, we support forming a student health club composed of elected student representatives and a teacher. These clubs promote hygiene practices schoolwide and keep handwashing stations well-stocked. This student-led model encourages a sense of ownership and responsibility.

Safe water and improved hygiene habits foster a healthier future for the entire school.

Rainwater Catchment

Rainwater Catchment

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project