Please note, original photos were taken before the pandemic.

The Mushiibi community is fertile with farming activities, varying from food crops like maize and beans to cash crops like sugarcane. At the time of our last visit it was the planting and weeding season, and we could see community members using cows to help plow their fields. The area is green with a variety of home styles. Some are mud houses, others are semi-permanent, and some permanent. It is a vibrant community, and people are observing COVID-19 restrictions and guidance by ensuring there are water and soap in each of their home compounds for handwashing.

The name Mushiibi translates to "problems" or "troubles", and comes from the village's inception. When people first settled here, there were poisonous thorns in the bushes where they began constructing their homes. They always identified the area by saying if the thorns pierce you, then you are "in trouble," because you would become very sick. Even though the thorns are no longer there, the name carried over to present day.

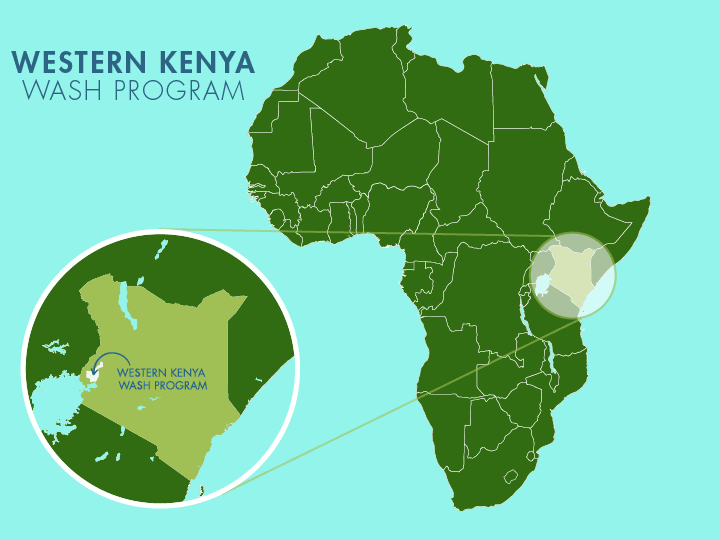

The area has a steep terrain leading to Ambani Spring, where 400 people in Mushiibi go for all of their daily water needs. But the spring cannot produce clean water, and the water is rife with contamination.

Women here begin their day by fetching water at 6:00 am, after which they prepare breakfast, send children to school, and the men leave to take care of milking and grazing the cows and goats. Around 9:00 am, the women leave for farm work and come back around midday. They prepare lunch for the children and then go fetch more water for the livestock to drink and for bathing. Some days they do laundry after coming home from the farm, briefly relax, or attend to other tasks like church meetings. Women then look for firewood before looking for what to prepare for dinner. They fetch more water for bathing, families eat dinner, and then everyone goes to bed.

Due to Kenya's national coronavirus-related school closures until 2021, students are home all day and parents are using them to help fetch water throughout the day. More people at home means higher water needs, so the added pressure at the spring is coming at a bad time when community members are trying to avoid groups and limit their time spent in public.

At the spring, we saw how the community attempted to protect the backfill area, but they did not have the technical knowledge of how to do it currently. There are haphazard layers of bricks, rice sacks, and rocks visible from the ground up with gaps between all of them. But the spring is still not sealed in, so contaminants trickle - and sometimes pour, if it rains - into the spring. Dirty surface runoff carries farm chemicals, animal waste, and extra soil into the water.

The community also placed a discharge pipe near the bottom of the mound, though we noticed a lot of water escaping around the pipe. This leads to slow fill times and adds to the crowds at the spring.

To fetch water, community members must try to balance on some rocks they placed at the drawing point, though sometimes they end up stepping or falling into the water and mud anyway. The pooling water is dangerous for people to stand in, as there are visible worms, called mahuhuni in the local dialect, that attack people's feet and sometimes their hands when they get wet. When it rains, the area around the spring becomes particularly muddy and slippery, making it difficult to safely access the water.

Because the discharge pipe is so low to the ground, it can be difficult for community members to fit their containers below it. If their container cannot fit, they must bring a smaller jug to fill, then pour into their larger containers. The whole of fetching water is time-consuming and frustrating, and accidental bumps into the pipe often dislodge more dirt and particles into the water they collect.

Waterborne diseases including typhoid, amoeba, and diarrhea are widespread in this community. Community members also report frequent cases of sore throats and stomachaches after drinking this water, along with the sore muscles and injuries that come from falling while trying to leave the spring area with heavy containers of water.

"This water has insects in it, and when I drink it I get a sore throat. We are afraid to use the water for drinking but we have no other solution," explained 50-year-old farmer and spring landowner Beatrice Ambani.

"I always become sick, especially stomach pains. When it rains, it becomes muddy and slippery," said primary school Romano while explaining how the unprotected spring affects him.

Community members have already mobilized the local materials needed for this project, and they are excited at the possibility of accessing clean and safe water from Ambani Spring for the first time.

"Our lives will never be the same again," said community member Paul Oliya, who has seen the life-changing benefits of clean water at Mabanga Primary School, where he works as a teacher.

What We Can Do:

Spring Protection

Protecting the spring will help provide access to cleaner and safer water and reduce the time people have to spend to fetch it. Construction will keep surface runoff and other contaminants out of the water. With the community’s high involvement in the process, there should be a good sense of responsibility and ownership for the new clean water source.

Fetching water is a task predominantly carried out by women and young girls. Protecting the spring and offering training and support will, therefore, help empower the female members of the community by freeing up more of their time and energy to engage and invest in income-generating activities and their education.

Training on Health, Hygiene, COVID-19, and More

To hold trainings during the pandemic, we work closely with both community leaders and the local government to approve small groups to attend training. We ask community leaders to invite a select yet representative group of people to attend training who will then act as ambassadors to the rest of the community to share what they learn. We also communicate our expectations of physical distancing and wearing masks for all who choose to attend.

The training will focus on improved hygiene, health, and sanitation habits in this community. We will also have a dedicated session on COVID-19 symptoms, transmission routes, and prevention best practices.

With the community’s input, we will identify key leverage points where they can alter their practices at the personal, household, and community levels to affect change. This training will help to ensure participants have the knowledge they need about healthy practices and their importance to make the most of their water point as soon as water is flowing.

Our team of facilitators will use a variety of methods to train community members. Some of these methods include participatory hygiene and sanitation transformation, asset-based community development, group discussions, handouts, and demonstrations at the spring.

One of the most important issues we plan to cover is the handling, storage, and treatment of water. Having a clean water source will be extremely helpful, but it is useless if water gets contaminated by the time it is consumed. We and the community strongly believe that all of these components will work together to improve living standards here, which will help to unlock the potential for these community members to live better, healthier lives.

We will then conduct a small series of follow-up trainings before transitioning to our regularly scheduled support visits throughout the year.

Training will result in the formation of a water user committee, elected by their peers, that will oversee the operations and maintenance of the spring. The committee will enforce proper behavior around the spring and delegate tasks that will help preserve the site, such as building a fence and digging proper drainage channels. The fence will keep out destructive animals and unwanted waste, and the drainage will keep the area’s mosquito population at a minimum.]

Protected Spring

Protected Spring

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project

Community members transplanted grass onto the backfilled soil to help prevent erosion. Finally, the collection area was fenced to discourage any person or animal from walking on it since compaction can lead to disturbances in the backfill layers and potentially compromise water quality.

Community members transplanted grass onto the backfilled soil to help prevent erosion. Finally, the collection area was fenced to discourage any person or animal from walking on it since compaction can lead to disturbances in the backfill layers and potentially compromise water quality.