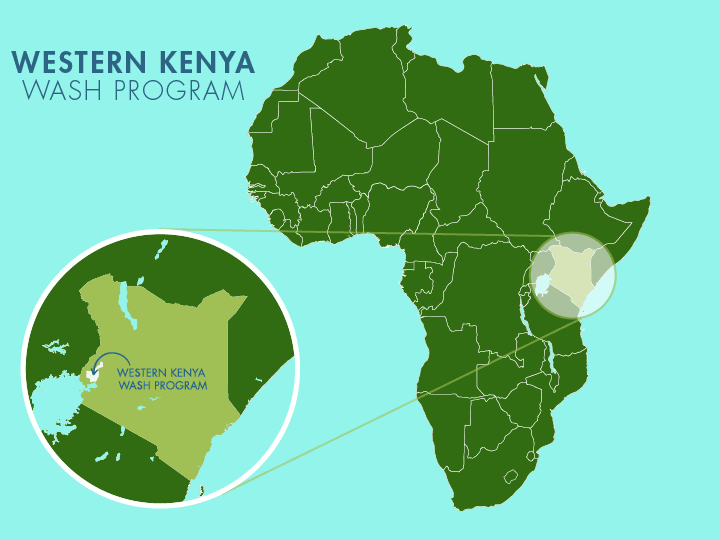

For the Elusolokha Community, access to safe and clean water has been a struggle that spans over two decades. The 150 residents depend on the unprotected Solomon Atsulu Spring, which is located far from many homes and across dangerous terrain. The narrow paths to the spring become slippery during the rainy season. The journey itself is tiring, but what awaits at the water source is even more disheartening.

The steep hill that community members must traverse to access the spring.

The spring is overcrowded, serving a large population that queues daily to scoop water with small jugs. Each person must wait for the murky water to settle before filling their containers. This slow process stretches into long hours, especially during mornings when everyone rushes to collect water for the day.

The water’s quality is poor, and its smell is unpleasant. Although one resident takes it upon himself to clean the area, contamination remains constant — the blue-green algae spreads quickly, and every rainy season brings new runoff and waste into the spring.

Field Officer Hosborn Bwana noted, “The water has greenish sticky growth atop it that gives it a smell of a dead toad, and it has lots of toads and tadpoles in it.”

Exposure to this polluted water has had a significant impact on the community’s health. Reports show frequent cases of typhoid, diarrhea, skin rashes, and other waterborne illnesses, particularly among children. The irritation caused by the algae leaves many young ones with stubborn, itchy skin conditions that persist even after treatment.

At just 14 years old, Mitchell knows the cost of unsafe water more intimately than most. She has fallen ill multiple times from drinking the contaminated spring water — illnesses that have affected her schooling, her confidence, and her dreams.

“It was just last month when I was diagnosed with typhoid, which leads to poor health, and seeking medication is so challenging to my parents because of [a] lack of funds. Someone gets waterborne diseases at least once a month in our household," Mitchell lamented.

Her experience with sickness was terrifying and unforgettable.

“I was so scared of death when I got sick. I had to stay at home for four days, waiting for my parents to get money for medication," she exclaimed.

The source of Mitchell's typhoid.

When her condition worsened, her parents had no choice but to borrow money for her hospital visit.

“My parents borrowed money to take me to the hospital for a test, and I was diagnosed with typhoid, which impacted my health negatively," Mitchell continued.

The impact of this recurring illness reaches beyond her health — it affects her education.

“I had to miss school for two weeks, which resulted [in] poor performance," she said.

Fetching water itself consumes much of Mitchell’s time. Although the spring is a vital lifeline, it is also a source of frustration and inequality.

Mitchell awaits her turn to collect the contaminated water.

“There is overcrowding at the spring because the water point serves a huge number of people. The overcrowding is mainly because we take a lot of time while scooping water using a jug which takes a lot of time. After one person scoops the water, we have to wait for it to settle before the next person draws it, and this also wastes time," she explained.

The overcrowding also exposes Mitchell to unpleasant experiences.

“I remember when my jerrican was pushed back by two women, and they had to fill about ten jerricans, scooping water using a jug, and I had to wait for them to finish," she recalled.

“It was so frustrating to me, and I had to miss school that day because I was waiting to fetch water."

Still, each morning she faces the same routine — fetching water before school, waiting in line, and missing valuable class time.

Mitchell collects water from the spring, which is in need of repair.

“It is so devastating to me when my mother sends me to fetch water. I wait for a long time, especially in the morning when I am sent to fetch water for drinking, which sometimes makes me miss school," she said.

Mitchell’s story reflects the experience of nearly every family in Elusolokha. The unprotected spring is not only far and overcrowded — it is also dangerous and unsanitary. For over 20 years, the community has endured this situation.

Mitchell.

Like many children in Elusolokho, Mitchell dreams of a better future — one where water is no longer a source of sickness and delay, but of health and opportunity.

“My future plan is to be a doctor, because I have been admiring that profession so much, especially when I visited the hospital whenever I was affected by water-related illness. I loved how the doctors helped people regain good health. Now with the construction of this water point, I have hope because accessing safe water will promote good health, and this will enable me to have enough time to study and get good results to pursue my dream career," shared Mitchell.

With safe water nearby, residents will no longer suffer recurring illnesses or spend hours queuing at the spring. For children like Mitchell, this change will mean fewer missed school days, improved health, and the freedom to focus on education and dreams rather than survival.

Protecting their spring will give her more than health — it gives her hope. With access to safe, clean water, Mitchell and her peers can finally look ahead to a future where children don’t fear sickness from a single sip, but instead, find strength in every drop.

Steps Toward a Solution

Our technical experts worked with the local community to identify the most effective solution to their water crisis. They decided to safeguard the existing flowing spring.

Spring Protection

Springs are natural water sources that originate from deep underground. As water travels through various layers of the earth, it undergoes a natural filtration process, making it cleaner and safer to drink. To protect these spring sources from contamination, we construct a waterproof cement structure around layers of clay, stone, and soil. This design channels the spring water through a discharge pipe, facilitating easier, faster, and cleaner water collection.

Chlorine Dispenser

As an extra measure towards water quality safety, uniquely engineered chlorine dispensers are installed at all of our spring protection projects so community members can treat their water with pre-measured doses of chlorine. The chlorine treats any possible contamination and stays active for two to three days, ensuring water stays safe to use even when stored at home. Chlorine delivery and maintenance of the dispensers are part of our ongoing community support.

Community Education & Ownership

Hygiene and sanitation training are integral to our water projects. Training is tailored to each community's specific needs and includes key topics such as proper water handling, improved hygiene practices, disease transmission prevention, and care of the new water point. Safe water and improved hygiene habits foster a healthier future for everyone in the community. Encouraged and supported by the guidance of our team, a water user committee representative of the community's diverse members assumes responsibility for maintaining the water point, often gathering fees to ensure its upkeep.

Protected Spring

Protected Spring

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project