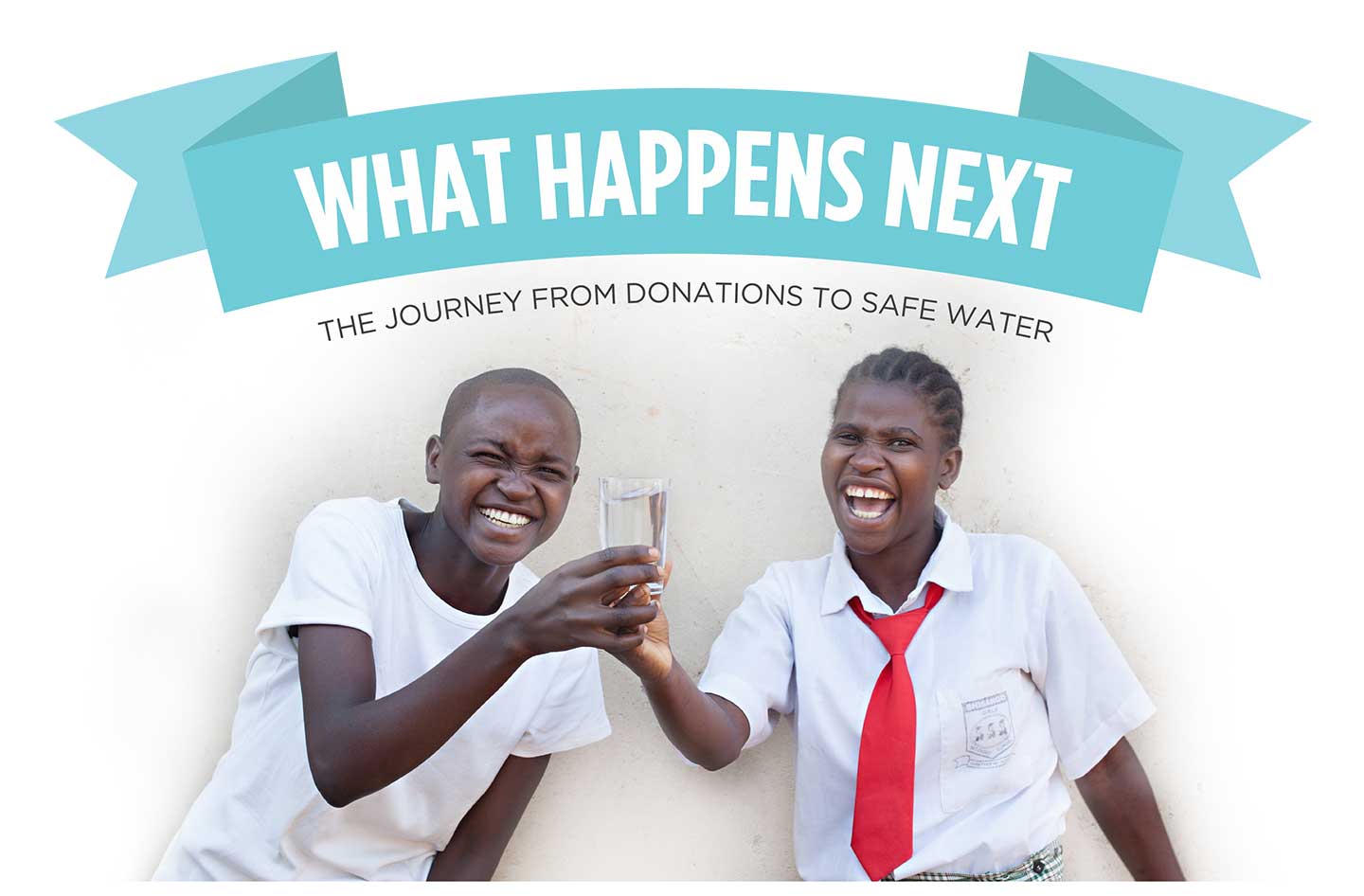

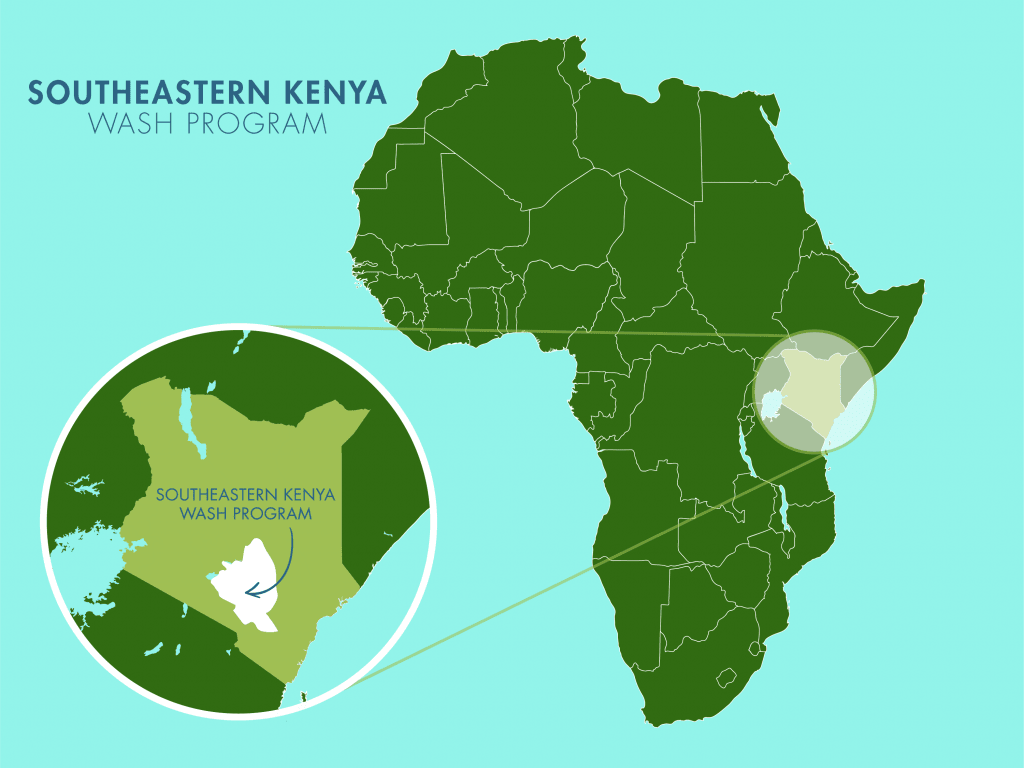

In the Wikwatyo wa Aka Kilulu Community—home to approximately 300 residents—daily hardships are faced due to long distances, steep terrain, and a scarcity of safe water.

Residents depend on two unreliable sources: a protected dug well and several open scoop holes dug into the dry riverbed. Fetching water from either source demands endurance. It takes between 30 minutes to two hours for each round trip, often under the searing sun and over dusty, rocky hills.

Collecting water from the scoop hole.

The scoop holes, the most common option for many households, are unprotected and easily contaminated by animals and debris. The water is often saline and unpleasant to drink. During droughts, the holes dry almost completely, forcing families to queue for hours as the water slowly refills.

Despite these challenges, families must make the trek daily, balancing jerrycans on their heads or backs across the rugged landscape. For children like Simon, this routine shapes every part of life — from school attendance to dreams for the future.

Simon, a 14-year-old boy, spends much of his day fetching water to help his family. The walk alone takes him through treacherous ground, and the scorching heat makes every step more difficult.

Simon at the distant well.

“The steep terrain with the immense solar heat makes fetching water an onerous activity. The water at the scoop hole also takes long to replenish itself during the drought period, and I have to wait. The protected shallow well and scoop hole are also quite far from my home.”

Simon spends about 90 minutes each day fetching water—time that steals from his studies, play, and rest. Like most children in the community, he balances schoolwork with household duties that revolve around water collection.

“I would spend my time playing with friends, going over my classwork, or helping my mother at home.”

Fetching water has not only taken away Simon’s free time, but also affected his education and safety.

“When I have to fetch water early in the morning or after school, I get very tired. Sometimes I arrive late to school, or I’m too exhausted to concentrate in class. Fetching water negatively affects my studies, and I wish I could spend that time revising or resting.”

For Simon, the dangers of collecting water are as real as the exhaustion that follows it.

“I’m worried about safety because the scoop hole where we fetch water is open and not protected. Animals also drink from it, and their waste and dust easily contaminate the water. During the dry season, the hole barely has any water, and I have to wait for hours as it slowly refills. Sometimes I’m alone out there, and it doesn’t feel safe, especially under the scorching sun with no shade around.”

The lack of water in his village brings daily frustration.

“There isn’t enough water because our area is very dry, and the river doesn’t flow all year. During drought, the scoop hole dries up almost completely. When I go there, it takes a long time to get just a little water. It makes me feel frustrated and tired because I have to wait for long, instead of doing other things like studying or helping my family.”

Simon dreams of a better future — one shaped not by thirst and fatigue, but by learning and compassion.

“I want to become a doctor. I’ve seen how people in my village suffer from waterborne diseases like typhoid and diarrhea, and I want to be someone who can help treat and prevent these illnesses. But I know I have to study hard to get there. If we had clean, nearby water, I’d have more time and energy to focus on my dream.”

Even in his youth, Simon’s awareness of how deeply water affects every part of life is striking. When asked how he feels about fetching water, his honesty reflects both exhaustion and quiet strength:

“I feel bad and angry because it is very exhausting, especially due to the steep terrain.”

Simon’s story mirrors that of the entire Wikwatyo wa Aka Kilulu Community.

The steep, rocky terrain makes every trip to collect water a laborious task. Families often ration what little water they bring home, sacrificing hygiene and comfort. During dry seasons, scoop holes shrink to muddy puddles, leaving residents vulnerable to typhoid, amoeba, and diarrhea. The exhaustion from hauling water prevents families from engaging in productive work like farming or livestock care, while children lose valuable study time.

Simon's long walk to water.

The community has made efforts to solve this crisis—seeking help from the county government and partners, and even building their first sand dam. But with only one dam serving a wide area, many still walk for hours to fetch water across difficult terrain.

The proposed installation of a protected well promises lasting change. The well will facilitate collection more easily and safely, eliminating the need to rely on open scoop holes.

This solution will drastically reduce the time and danger of fetching water, improve health by minimizing exposure to contaminated sources, and give children like Simon a chance to rest, study, and thrive. For adults, it means more time for farming, small business, and community development.

The Wikwatyo wa Aka Kilulu Self-Help Group has clear goals once water is secure. They plan to plant trees, grow vegetables, improve livestock care, and terrace their land to prevent erosion and boost food production. With access to water, these plans can finally transition from hope to action—strengthening both household income and environmental resilience.

For Simon, it means no longer walking for hours under the burning sun—it means time to study, play, and dream of becoming the doctor who will one day help his community heal.

Solving the water crisis in this community will require a multifaceted system that will work together to create a sustainable water source that will serve this community for years to come.

Steps Toward a Solution

Our technical experts worked with the local community to identify the most effective solution to their water crisis. Together, they decided to construct a protected dug well and sand dam.

Protected Dug Well Near A Sand Dam

Once a sand dam is installed and has time to mature by gathering sand and silt, groundwater increases significantly in the entire area surrounding the project. This provides a reliable source of groundwater that wasn’t possible before. As a result, wells can be constructed to take advantage of the water stored and filtered in the collected sand.

During the construction of the protected dug well, we will build a platform for the well and attach a hand pump. The community will gain a safe, enclosed water source capable of providing approximately five gallons of water per minute.

This protected dug well will be connected to a sand dam to obtain water.

Community Education & Ownership

Hygiene and sanitation training are integral to our water projects. Training is tailored to each community's specific needs and includes key topics such as proper water handling, improved hygiene practices, disease transmission prevention, and care of the new water point. Safe water and improved hygiene habits foster a healthier future for everyone in the community.

Encouraged and supported by our team's guidance, the community elects a water user committee representative of its diverse members. This committee assumes responsibility for maintaining the water point, organizing community efforts, and gathering fees to ensure its upkeep.

Protected Dug Well

Protected Dug Well

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project