Every morning before the sun climbs too high over the rooftops of Tintafor Community, eighteen-year-old Adamsay begins her daily journey for water. She balances a bucket on her head, its hard plastic already warm from the early heat. The path is familiar — a long, dusty walk that takes her past houses, through open fields, and down the road toward the nearest well. It’s a trip that can take more than half an hour each way, sometimes longer if the queue is long, which it often is.

Adamsay.

Adamsay's community has 165 residents. Her neighborhood is home to many families and several members of the Orthopedic Rehabilitation and Medical Services group — a local organization that supports People with Disabilities (PWD). For everyone here, finding water is a daily struggle. For the elderly, people with disabilities, and young girls like Adamsay, who often struggle, it can feel overwhelming.

There are only two places where community members can fetch water. One is a private well near a bakery, built for the bakery’s use. The other sits inside Saint Augustine Secondary School, behind a fence and a locked gate. Both are more than thirty minutes away from most homes, and both have restrictions in place. The bakery’s well can only be used at certain times, and at the school, people wait for permission to enter. When school is in session, the gate often stays shut.

“Sometimes,” she said, “I must wait for them to open the gate before I can fetch water. When they open, many people rush, and we stand in line for [a] long [time]. By the time I return home, it is already late.”

Sometimes she walks even farther, past Saint Augustine’s, to another neighborhood in search of an open well. “It is not easy,” she explained. “The rubber [bucket] hurts my head, and my legs pain me.”

Making the long walk.

The struggle is worse for the people with disabilities living nearby. Many cannot walk long distances or carry water themselves. Some must pay others to fetch water for them, while others go without.

Field Officer Alie Kamara described how these challenges isolate them from the rest of the community: “Their colleagues in Freetown often visit, but because of the water problem, they don’t stay long. There is no water for them to use.”

Adamsay dreams of becoming a medical doctor. She wants to help people, to give health talks, and treat those who are sick. But her dream feels far away. Each day, she spends nearly five hours fetching water, time she could have spent studying.

“Sometimes I go late to school,” she admitted. “Other times, I cannot go at all. If I do not wash my uniform, it will not dry in time, and I will miss class.”

When she does make it to class, she is often tired. The long hours of walking under the sun leave her drained, her body aching from carrying heavy containers.

Yet she remains determined. “If we had a borehole in our community,” she said, “I would have more time to study. I would not miss school. I want to be a doctor one day — to help people.”

As Field Officer Alie Kamara reflected, “For a community to develop, there must be sustainable access to water.”

In the Tintafor Community, that truth is felt every day. Without water, children lose their chance to learn. Women lose time and income. People with disabilities lose their independence.

However, with clean water nearby, everything could change.

For Adamsay, it would mean mornings spent preparing for school instead of walking to distant wells. For people with disabilities, it would mean dignity — the ability to care for themselves without depending on others.

Tintafor Community is ready for that change. The community knows that water is more than just a daily need — it is the foundation for health, education, and opportunity. A borehole here would not only end the long walks and waiting lines; it would open the door to a brighter future.

As Adamsay said, “Water is life. When we have it near, everything will be better.”

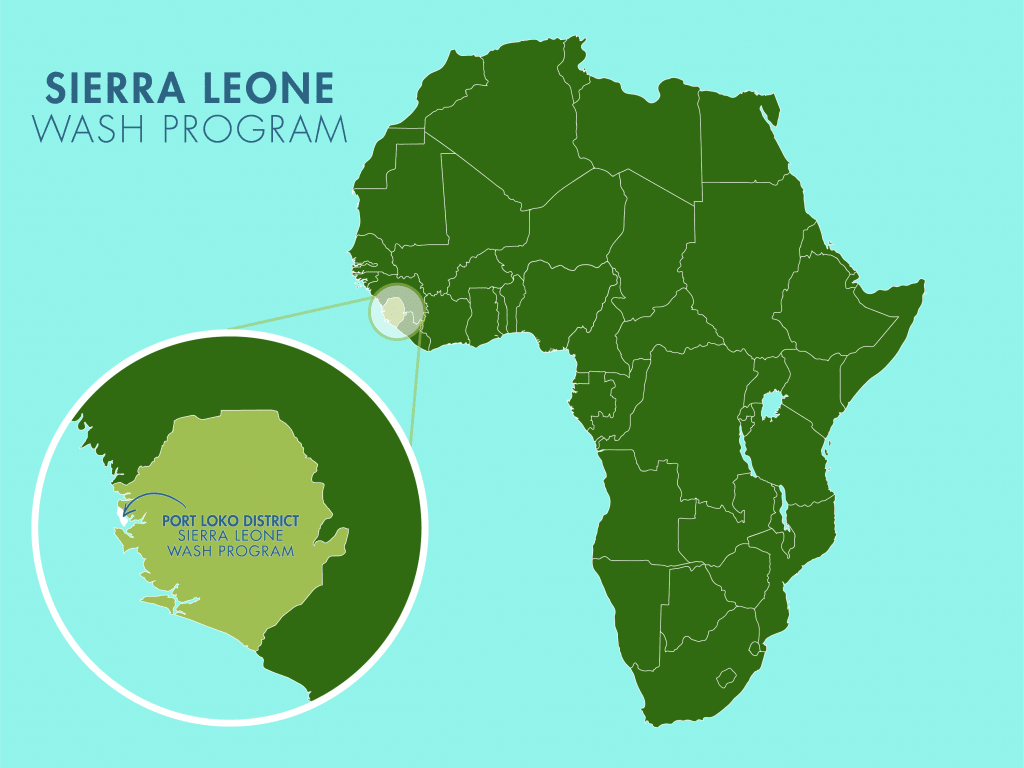

Steps Toward a Solution

Our technical experts worked with the local community to identify the most effective solution to their water crisis. They decided to drill a borehole well, construct a platform for the well, and attach a hand pump.

Well

Abundant water often lies just beneath our feet. Aquifers—natural underground rivers—flow through layers of sediment and rock, offering a constant supply of safe water. A borehole well is drilled deep into the earth to access this naturally filtered and protected water. We penetrate meters, sometimes even hundreds of meters, of soil, silt, rock, and more to reach the water underground. Once found, we construct a platform for the well and attach a hand pump. The community gains a safe, enclosed water source capable of providing approximately five gallons of water per minute. Learn more here!

Community Education & Ownership

Hygiene and sanitation training are integral to our water projects. Training is tailored to each community's specific needs and includes key topics such as proper water handling, improved hygiene practices, disease transmission prevention, and care of the new water point. Safe water and improved hygiene habits foster a healthier future for everyone in the community.

Encouraged and supported by our team's guidance, the community elects a water user committee representative of its diverse members. This committee assumes responsibility for maintaining the water point, organizing community efforts, and gathering fees to ensure its upkeep.

Borehole Well and Hand Pump

Borehole Well and Hand Pump

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project