Why Becoming Educated is Hard in Sub-Saharan Africa – Especially for Girls

Here in the United States, late summer is the time of year when kids and parents alike start thinking about heading back to school. In the U.S., the process involves kids getting supplies, meeting teachers, and maybe even scouting the trendiest outfits. It’s unlikely that any U.S. parents are worried about whether the kids will have enough water to drink or a place to go to the bathroom.

But in sub-Saharan Africa, parents endure those worries every day, because less than half of the schools in the region have water.

Everything about getting a good education is harder in sub-Saharan Africa. Not only is it difficult for parents to enroll their children in school, but students (especially girls) struggle to stay in school once they’re enrolled.

Of all regions, sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of education exclusion. Over one-fifth of children between the ages of about 6 and 11 are out of school, followed by one-third of youth between the ages of about 12 and 14. According to UIS data, almost 60% of youth between the ages of about 15 and 17 are not in school.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

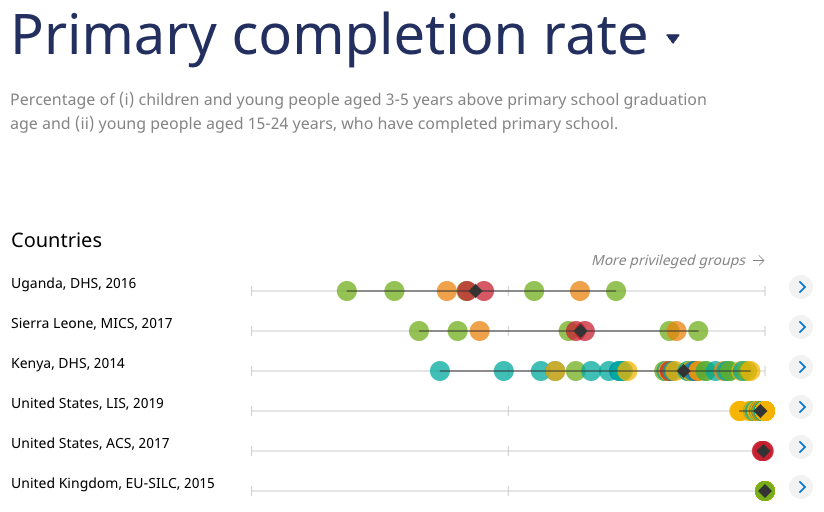

In the countries we serve (Kenya, Uganda, and Sierra Leone), the low rates of students who complete their education are striking — especially in comparison to wealthier nations.

Believe it or not, education statistics have improved in Africa over the past 50 years or so. But still, nearly a third of all children in Africa don’t complete primary school.

Why does this problem persist?

Reason #1: Poverty (School Fees & No School Lunches)

Schools don’t receive as much support from their governments in sub-Saharan Africa. 86% of Africans work in informal (non-taxed) jobs like subsistence farming and trading, which means their governments are missing out on revenue that could help develop schools and their students.

As such, many schools charge fees for enrollment. In a region dogged by poverty, school fees that may sound small to some Americans represent a large percentage of a sub-Saharan family’s annual income. And in addition to school fees, parents end up paying for other essentials, too.

Even in countries like Uganda, which offers free primary education, parents still have ancillary school expenses for uniforms, exam fees, school upkeep, books, or hiring an extra teacher. The cost of sending a child to school in Uganda varies from US$168 for government schools to US$420-680 for private schools. At the same time, more than 60 percent of adults in Uganda are very worried about school fees; for 40 percent of adults, school fees are the biggest source of financial worry. This is not surprising, as about 42 percent of Ugandans live below the poverty line of US$2.15 per day (about $785 per year).

World Bank

While numerous studies have shown that eliminating school fees would significantly raise enrollment rates, there are no schemes to replace that funding once it’s gone. This would be a huge burden for the 54% of schools that already can’t provide their students with necessities like a basic source of water on school grounds. But with many parents unable to pay the high educational fees, the cycle of poverty in a community will only continue.

Students in communities without reliable water sources suffer more when it comes to education costs. Parents often need water for their livelihoods; without ample water to supply industries such as farming, food trading, soap-making, and palm oil production, their household funds rapidly deplete.

“My parents’ level of income…reduces because they [cannot] cultivate [many] crops during the dry season, which ultimately affects my studies, because they cannot raise enough [money for school] fees or [to] buy books for my studies,” said 14-year-old Caroline M. from Thonoa Community in Southeast Kenya.

Families also find all their income channeled into treating water-related illnesses.

Caroline continued: “I also have to carry water to school, which leads to exhaustion due to long distances from home to school. The water from the scoop holes is also contaminated, making me sick occasionally and unable to attend classes.”

13-year-old Sarah from Shikokhwe Community in Kenya had a similar problem before The Water Project protected the spring in her community. “Many of us have been facing different problems, like being infected with water-related diseases, causing us not to attend school, and financial constraints, as a majority of people use the little money they get for health services instead of paying school fees for children like me.”

Daily life becomes even more difficult for students and parents when a lack of water causes the school’s normal programs, like school feeding (lunch) programs and extracurricular activities, to pause or stop altogether.

“It’s not been an easy thing, managing a school without water,” said Principal of Friends Mixed Secondary School Lwombei Henry Okare Amoke. “We normally have a school feeding program for tea breaks and lunch, and it requires water, as does the cleaning of the toilets and classrooms. Without water, all of these things suffer.”

To keep these essentials going, principals and headteachers sometimes need to send students off school grounds in search of water, often during class: another blow to students’ morale and learning.

Reason #2: Walking Long Distances

Almost a quarter of children in sub-Saharan Africa live at least two kilometers away from the closest school, with no school buses to come and get them each morning.

“I have to walk about five kilometers (3.1 miles) to school carrying water in a jerrycan every day, which leaves me too tired to concentrate on my studies,” said 11-year-old Janet, who attends Mutiuni Primary School in Southeast Kenya. “Also, I have to forego coming to school when there is no water at home to avoid punishment from the school administration.”

Some parents opt to keep their children from school until they’re older in order to shelter them from the strain and potential dangers of walking to and from school every day.

“I am 16 years of age but still in primary school,” said 16-year-old Sulaiman S. from Kriema Kiamp Community in Sierra Leone, where The Water Project rehabilitated the well last year.

“My parents did not enroll me in school until I was 11 years [old] in fear of something happening to me during the long walk. Most children suffer the same fate as me, which will later discourage us from continuing our education. In these parts, the dropout rate is also very high due to early marriages for the young girls and early family responsibilities for the young boys. Education is valued only by a few people who have directly benefitted from it.”

The extra trips to collect water during school hours also create additional risk to younger students and to girls who already risk assault on the long treks to and from school.

Our field officer Nelly Chebet described this at Siekuti Primary School: “The water crisis in the school really impacts the students negatively because most of them waste a lot of time looking for water far away from the school compound, and also going to a steep area, which is very risky, especially to a girl child. [This] can lead to rape cases, which may lead to unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, contributing to high cases of school dropouts.”

Reason #3: Lack of Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene

In sub-Saharan Africa, many administrators ask students to bring water with them to school from home to supplement the schools’ unreliable supplies. However, all that walking compounds the draining effects of an already-long journey and leaves kids too tired to listen in class.

“Personally, [I] am tired of coming to school because when I think of how there is no water in school, it makes [me] hate school,” said 14-year-old Peninah from Kuvasali Primary School in Western Kenya, which received a rainwater harvesting tank in 2022.

“Sometimes, I carry drinking water from home to school, but it’s not enough, because sometimes I share with my classmates, who also need water,” Peninah explained. “This has affected my studies a lot because I know drinking water helps a person to be alert, but here in school, without water, I always feel sleepy, and I miss what the teacher is saying.”

And the problems don’t stop there. Because the schools don’t have enough water, they end up rationing what little they have. Often, this means a school can’t be cleaned as often as it should.

“[The] lack of enough clean water to drink and use in school has made me hate learning. This is because most of the time my hands are dirty, the classrooms are dusty, and the latrines are also dirty, and to make matters worse, sometimes we have no water to drink because the water from home is dirty,” said 14-year-old student Clonton K. from Gamudusi Primary School in Western Kenya, where we installed a borehole well in May.

“Carrying water to school is difficult, considering we sometimes have to carry firewood to school,” said 11-year-old Kevin K. from Nguuku Primary School.

“I arrive [to] school late and exhausted, which affects my concentration in class,” Kevin continued. “For instance, yesterday, I arrived late because the scoop hole was overcrowded ([with] community members and livestock), and I had to wait for my turn. The water is also insufficient; therefore, we only sweep our classes and mop them once or twice in a term. This makes the learning environment unconducive. The latrines are also rarely cleaned, thus emitting a foul smell, and we have to remove our sweaters and leave them outside to prevent the odor from remaining on our garments.”

Reason #4: Being Born Female

While the obstacles for all children trying to learn their way out of poverty in sub-Saharan Africa are staggering, girls bear the brunt of this adversity. Here, many girls drop out of school once they reach puberty.

“Across the region, 9 million girls between the ages of about 6 and 11 will never go to school at all, compared to 6 million boys, according to UIS data. Their disadvantage starts early: 23% of girls are out of primary school compared to 19% of boys. By the time they become adolescents, the exclusion rate for girls is 36% compared to 32% for boys.”

UNESCO

Worldwide, of the 17 countries in the world where girls haven’t caught up with boys in primary school enrollment, 12 of them are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Part of this disparity is because women in sub-Saharan Africa do more unpaid domestic work, like cooking, cleaning, caring for children and sick people, and fetching water. For those things, girls don’t need formal education. We’ve covered this phenomenon in a previous article about how a lack of access to water often translates into child marriages (sub-Saharan Africa has the highest rates of child marriage in the world) and, ultimately, domestic violence.

But while education might prevent a girl from entering into such a marriage, it might also provide opportunities to be preyed upon.

“My journey of education has not been an easy one here. Getting water each morning almost cost me one day when I was almost raped as I went downstream to get water from the river that is surrounded by dense vegetation,” said 18-year-old Melvin A from Friends Mixed Secondary School Lwombei.

At some schools, simply having enough latrines is a problem, let alone latrines with adequate privacy and a maintained place for girls to dispose of their used sanitary products during their menstrual cycle. With there still being a lot of stigma about periods in Kenya, Uganda, and Sierra Leone, this lack of facilities means girls skip school during their periods and miss lessons.

“…the limited availability of clean, accessible water and sanitation facilities in many low and middle-income countries augments the challenges girls and women face in conducting daily activities while managing vaginal bleeding, including participating in school or work, going to the market or fetching water.”

BMJ Global Health Journal

“As the head of the school, it is my responsibility to make sure that water, hygiene and sanitation facilities are within reach of all students and staff,” said Headmistress Frances Kanu from Kulafai Rashideen Primary School in Sierra Leone.

“Having this many children with no adequate water supply is simply disturbing and endangers their lives. The condition of the school, water well, and latrines are in very bad shape. The condition of the latrines could be amended when the water issue has been resolved. I most times have to go to my house to drink and use the latrine. With water being in short supply, a woman or young girl experiencing their menstrual cycle will surely miss school sessions.”

How to Help

While there are great systemic strides that still need to be taken in order to ensure equal education for all in sub-Saharan Africa, what comes to light when you examine the everyday lives of kids enrolled in school (and those missing out), is that clean water transforms education availability, quality, sustainability, and enjoyment.

As the countries in our service areas continue to gain independence and momentum, we have high hopes that the needed infrastructure will develop (however slowly). In the meantime, you can help kids trying to educate themselves by choosing a school to support from our upcoming project list or donating what you can and letting us decide where the most immediate need is. With every donation, we’ll provide periodic updates via email with the water project’s progress, the status of the school or community, and quotes and photos from the people you’ve helped.

Home More Like ThisTweet