But What About the Teachers? How the Water Crisis Endangers Everyone at a School

When we build water projects at schools, our instinct is always to talk about the students.

But with going back to school at the top of everyone’s minds, we’re taking a moment to appreciate the teachers behind the water crisis. They deserve recognition for educating their students despite the odds stacked against them.

Where we work in sub-Saharan Africa, only 45% of schools have water sources. Still, even schools with their own water sources struggle due to sub-Saharan Africa’s water shortages.

African kids suffer most from water-related illnesses like typhoid, cholera, and others because of their immature immune systems. But their teachers must also deal with the pain (and the price) of being ill.

“Personally, I have always suffered from typhoid, and it is expensive to treat,” said 36-year-old teacher Geofrey Kipkorir from Museywa Primary School in Kenya. “A lot of money is spent on my medication, and this has led to poor performance in the class that I teach because, most of the time, I am at home seeking medication.”

Even if drinking a school’s water doesn’t usually make people sick, water stress itself still causes illnesses. When students and staff can’t properly clean their classrooms or latrines or fill their handwashing stations with water, infection increases significantly.

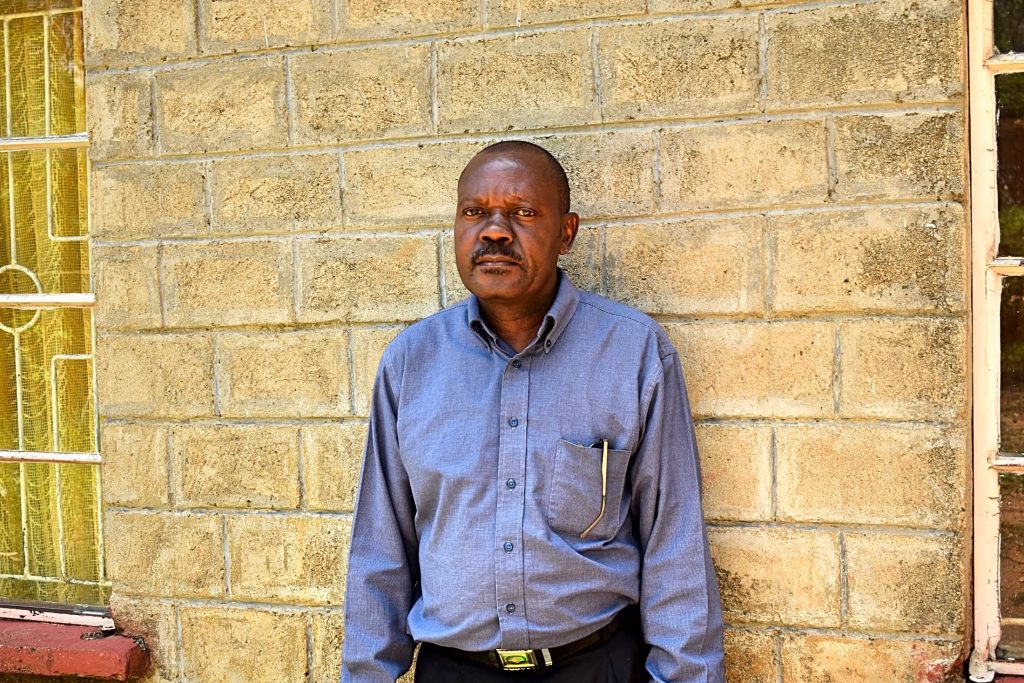

“When I first felt sick in 2014, I thought it was just the normal malaria, but it turned out to be [a] bacterial infection which was caused by contaminated water from the school,” said senior teacher Benson Wagara from Ebubole UPC Primary School in Kenya.

“After treatment, all was well until the year 2021 when the same condition occurred, which prompted me to [get] a test on typhoid, of which the results from the laboratory showed positive,” Benson continued. “Ever since that time, I have resorted to boiling drinking water and [carrying] my own [water] from home everywhere I go to prevent any other health problems.”

But a school’s water crisis doesn’t only affect the school community’s health. Headteacher Serah Kilonzo from Kanyuuni Primary School explained in detail how the lack of water affects the everyday running of her school.

“We have had to stop irrigating crops that help in studying agriculture; hence, the performance in the subject has dwindled,” Serah said.

“Construction projects within the school cannot be accomplished because of the acute shortage,” Serah continued. “The school’s facilities also suffer from poor hygiene and sanitation because we do not mop our classes throughout the term, and [our] latrines have contracted a foul smell.”

“The water availed by students and the [water] vendor is acquired mostly from contaminated scoop holes or unprotected dug wells, which exposes students to complications like stomachaches and diarrhea related to typhoid or amoeba,” Serah concluded. “Every term, more than a dozen pupils are absent from school after contracting water-related infections.”

As you can imagine, teaching students anything in a school suffering from water scarcity is an enormous challenge. The lack of success affects students’ futures, which, in turn, hurts the morale of the teachers.

“As teachers, our joy is to have excellent performance from our students, but unfortunately, their result is not only limited to our efforts but also the learning environment,” said teacher Vincent Iganza from Jeblebuk Primary School in Kenya.

“Our school lacks a reliable water source, the sanitation facilities are filthy, and handwashing stations are not enough,” Vincent continued. “We pray and hope that these issues will be solved so that our school can shine academically.”

“Life has not been good for us,” said teacher Mary Waisaya from Muhaya Primary School in Kenya. “[The] lack of enough clean water has really affected our school program in terms of syllabus coverage and also attending classes. Some of our pupils miss lessons. As a teacher, concentrating on teaching a few pupils becomes a challenge.”

At the time of writing this article, all the above teachers, students, and schools are still waiting for water projects. But once they do receive water sources of their own, cases of water-related illnesses will reduce. Kids can stay in class and not leave school grounds to fetch water, making it easier for teachers to cover their syllabi and for students to perform well on exams. And, hopefully, teachers will regain their love for teaching — as Lucy Ndiso did.

A year after we installed a high-capacity rain tank at Kyuasini Primary School, we revisited the school (as we do all schools, communities, and health centers where we work). Teacher Lucy Ndiso narrated the inspiring transformation her workplace had undergone.

“Before the construction of the water tank, we did not have enough water in the school,” Lucy said.

“The pupils suffered a lot in getting water. In the morning, a pupil attending Kyuasini Primary School would be identified by a jerrycan of water. This was [a] very hard task for young kids, bearing in mind they’d walk for several kilometers every single morning. At times, the pupils would be forced to rush [to] the nearby river at lunch or even [during] game break time.

“Now, the pupils do not need to carry water anymore. In the school, we have a feeding plan which needs [a] reliable water supply. This has been made possible because of the availability of water in the school. We are able to get enough water to serve the pupils in the school every time.”

“In the past year, our school has become very clean and welcoming,” concluded Lucy. “We managed to plant some vegetables, although they have not grown so big, but we hope they shall. We have enough water for drinking, cooking, and washing our hands hence avoiding germs.”

As the years go on, we hope that Kyuasini Primary School’s agricultural program flourishes along with its students and teachers — just as we hope that we can bring water projects to other schools still waiting.

A school’s access to clean water is not just quenching the school community’s thirst during the day. It’s about keeping kids happy, healthy, and learning, and the teachers healthy and motivated. With so much of the world depending on our teachers’ shoulders, we are thankful and proud to be part of a solution enabling educators to thrive.

If you’d like to join us in creating that solution, take a moment to look through the schools we hope to help this year and choose which one speaks to your heart the most.

Home More Like ThisTweet