How Seasons Affect Water Availability in Southeast Kenya

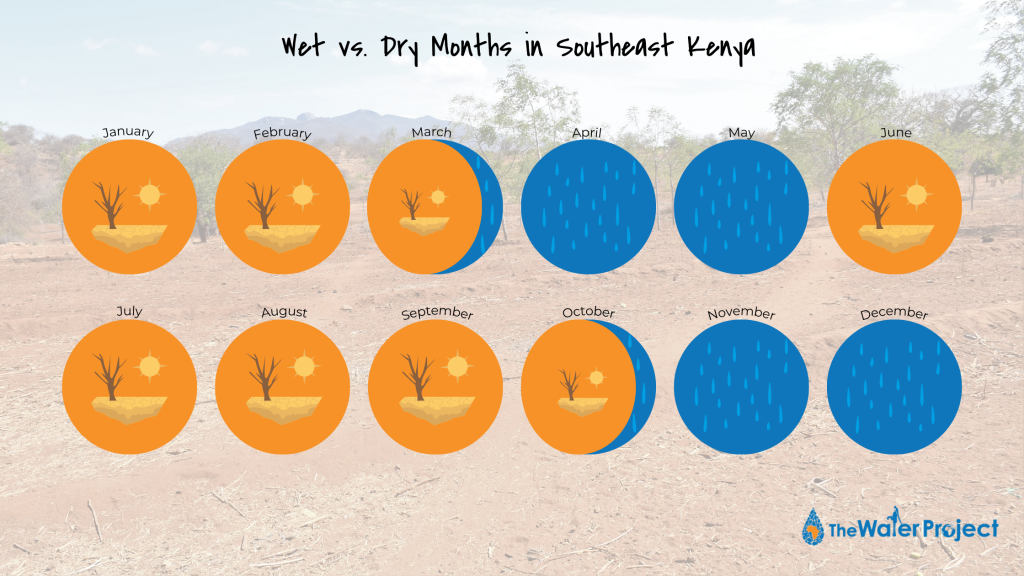

Where The Water Project works in Southeast Kenya, there is no spring, summer, autumn, or winter. There are only wet months and dry months. And, unfortunately, according to staff and community members who live there, the dry seasons have been expanding in recent years, which makes accessing clean water challenging, to say the least.

“[The] Southeast Kenya region experiences a hot and dry climate with two rain seasons in a year,” said Communications Officer Titus Mbithi, who works on our local team in Southeast Kenya.

“Due to climate change, the rains start in late March and late October, meaning [the] better parts of the two months are dry. The dry season is characterized by low water availability and access, leading to community members walking for long distances to the few available water points.”

The extended dry months create massive problems for community members.

“This area is prone to long drought periods, which causes the scoop hole to offer little water,” said 36-year-old farmer Lazarus Mwendwa from Kamukithe Community in Southeast Kenya, where we’re hoping to install two projects in 2024.

“Residents from far away also come here to draw water during peak drought periods because scoop holes near their homes dry up. Water is life. It means a lot to me as a farmer because I need water to earn an income. Without water, I will not be able to provide food for my family, and my children will be sent home for school fees.”

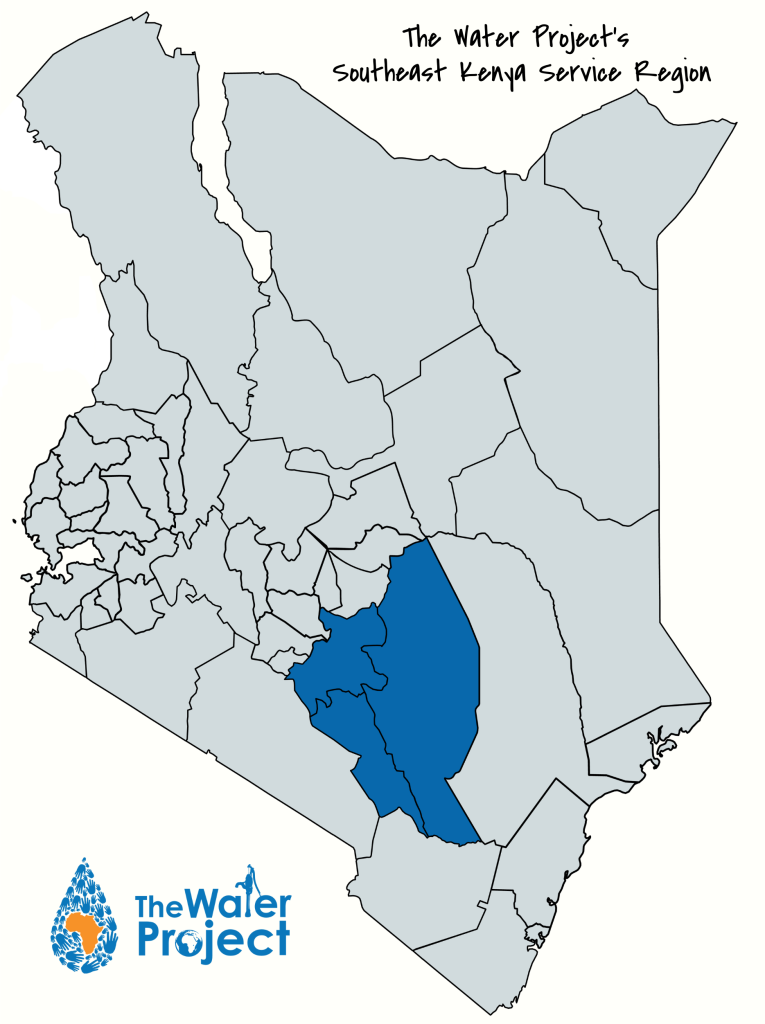

Where We Work in Southeast Kenya

The Water Project works within three counties in Southeast Kenya (Kitui, Makueni, and Machakos). And while the area may look small on a map, it’s semi-arid (semi-dry) and sparsely populated, with people living far away both from each other and from the area’s seasonal rivers. This means there’s a lot of land for everyone to cover before they can reach any water.

Because everyone is so spread out, this area is where we see the farthest and most time-consuming travel times to water sources. People often leave on foot before dawn and do not return home with water until midday. Those who can afford them raise donkeys to help haul water, but others can’t afford help, bringing home only what they can carry themselves over the harsh distances.

The journeys to safe water sources are prohibitively long, so people are forced to dig scoop holes into seasonally dry riverbeds. But the scoop holes’ brown, salty water makes the people who drink it sick.

“The scoop holes expose me and my family to infections, such as typhoid, stomach upsets, and more, because they are contaminated by livestock [excrement] and dust. My son, Nzangi, developed stomach issues recently, and the other children often complain of similar symptoms as well,” shared Benjamin Muthui, a 65-year-old farmer from Makioni Community.

The huge differences between the seasons alter the landscape. Just imagine what happens to the water beneath the surface of the Earth. Then, imagine what happens to the people, animals, and farms when the rain is late in coming.

“The community in this region is agropastoral and highly relies on rainfall performance for the success of their crops and livestock,” Titus explained.

“Agropastoral” means the people here rely on both farming and livestock-rearing for food as well as income. When water becomes increasingly more difficult to find during the extending dry seasons, everyone who lives here suffers.

“During the dry periods, water access is a big challenge as seasonal rivers, [and] earth dams run dry, leading to long walks to the few available water points, which end up being depended upon by a large number of people,” Titus said. “The dry season poses major challenges to our users.”

But according to Titus, water problems don’t disappear during the wet season, either. Then, rainfall washes whatever’s on the ground into the rivers: animal dung, garbage, farming chemicals, human waste — the list goes on, and none of it is good.

How The Water Project Helps Communities

Such staggering challenges might make you wonder about the solutions. After all, how can you provide water where there is none?

For us, the answer is sand dams.

Instead of holding back a pool of water, sand dams build up a reservoir of silt and sand. Following a sand dam’s first rainy season, the sand will capture 1-3% of the river’s flow. Almost all of the river water flows over the dam. Then, we construct shallow wells on the riverbank to provide water even when the river has dried up, thanks to new groundwater reserves. And although the river’s water may look brown in photos, the water underground, where our wells reach, is filtered by all the silt and sand.

This two-pronged approach not only addresses the immediate need for water but also helps to mitigate health risks. By providing closer access to clean water, we help shield communities from waterborne diseases, ensuring that stories like Benjamin Muthui’s become a thing of the past.

Sand dams and shallow wells offer a buffer against seasonal extremes, securing a year-round water supply that supports not only human health but also the productivity of crops and livestock.

What About Schools?

In our other service areas, we drill wells for schools. But in Southeast Kenya, we would have to drill so far beneath the surface of the earth to reach water that drilling a borehole well is not viable logistically or economically.

Instead, schools get their own rainwater harvesting tanks. Each tank we install in Southeast Kenya holds a whopping 104,000 liters of water because of how rarely it rains in Southeastern Kenya (our rain tanks in other areas aren’t nearly this large!). With a larger amount of water stored during the seasonal rains, it is far less likely for the tanks to empty out during the extended dry seasons.

Conclusion

It’s only through the generosity of our donors, the dedication of our teams, and lessons learned that we’re able to transform lives effectively through the power of clean water — even in a dry region like Southeast Kenya.

“We experienced water scarcity because this area is semi-arid, and the nearby rivers are seasonal. We used to walk over five kilometers to [the] nearest waterpoint,” said 29-year-old farmer Muyathi Mwanza from Kasioni Community in Southeast Kenya.

“We had to travel several kilometers searching for water, which left me tired and unable to concentrate on activities like farming. Also, there was meager water for household activities due to the lengthy dry seasons.”

Since the installation of the sand dam in Muyathi’s community in 2021, community members have had access to water, opening up time and energy to do other things.

“I now spend less time looking for water because the water point is nearby and offers a steady supply of water even during the dry months. This has allowed me to focus on other developmental activities, such as farming and rearing cattle. I can now plant trees because of the sand dam’s water availability, which will change my environment in the long term.”

Home More Like ThisTweet