What we learn together

Continued Learning from Water Point Mapping and Vetting

Assessing and Planning for Coverage

The Water Project is committed to ensuring 100% coverage of safe and reliable water access in the areas where we work. This means that everyone in a community will have water within a 30-minute round-trip walk of their home; all students will have water available at their schools; and all healthcare facilities will have the water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure they need to provide quality care.

The first step in planning for full coverage is water point mapping. By identifying all of the water sources people are already using, we can empower our local teams to plan water projects that systematically approach 100% coverage.

We are excited to share that comprehensive water point mapping activities have now been completed in three of our four focus regions: Western Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Uganda. Upon completion of the water point mapping in Sierra Leone, our teams had located and assessed over 22,000 water points, 840 schools, and 137 healthcare facilities. It was an enormous effort on behalf of our local teams, and means we have exciting new opportunities for systematically expanding our work together.

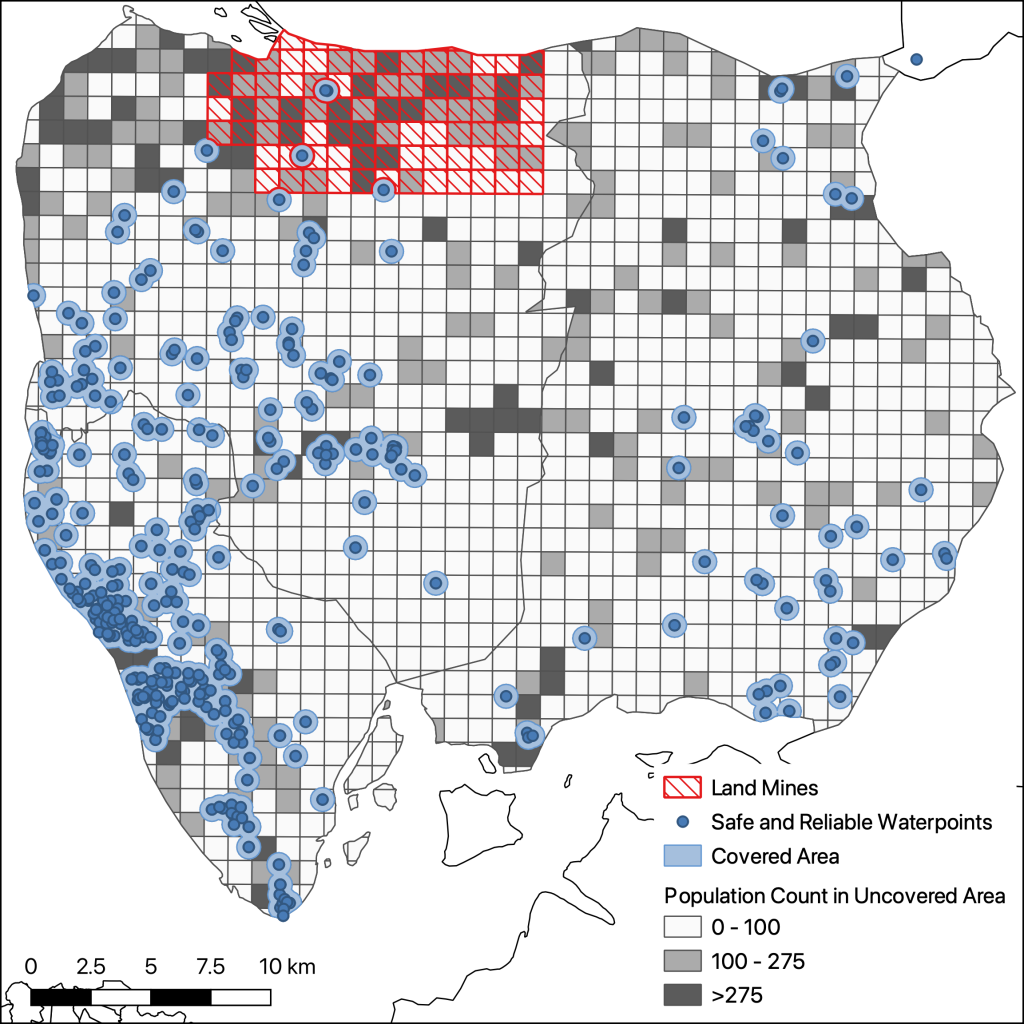

Water point mapping data can be used in so many ways, but the first thing we do at The Water Project (TWP) is to identify who already has access to safe and reliable water access and who doesn’t. Combining information on existing water sources and population density data helps us prioritize projects to bring water to those who are most in need. The example map of our Sierra Leone focus region below shows the areas where The Water Project considers people to be covered (having water access within a 30-minute round-trip walk) in blue. Everyone else, we see in gray. These are the people we consider to still be in need — new water sources will need to be established for those people before our work is done.

Through this coverage analysis, The Water Project is able to estimate the number of people still in need of water across all Western Kenya, Uganda and Sierra Leone – we now know that over 450,000 people still need water.

Continuous Learning

At The Water Project, we have developed this methodology of assessing and planning coverage to be as accurate as possible, in close collaboration with our local teams. However, we recognize that there are lots of things that you don’t see on these coverage maps. We don’t see, for example, the geological makeup of the earth in these areas or the availability of groundwater; we don’t see the critical patterns of rainfall that determine whether rainwater harvesting is a viable solution; and we don’t see the political and social dynamics of government collaboration or community engagement that are key factors in decision-making.

The complexity of implementing water projects in these regions can be challenging at times, but it also gives us an opportunity for constant learning and engagement with those closest to the issues. For that reason, The Water Project considers the mapping to be a base on which we will continue to build our knowledge. In the first half of 2024, The Water Project has worked with our local teams to close vital information gaps and strengthen our baseline understanding.

Our first mapping priority in 2024 was to return to our Western Kenya service area and gather more in-depth vetting information on its unprotected and partially protected springs. During our mapping activity in Western Kenya, we identified over 4,000 springs in various states of functionality. In Western Kenya, spring protection works well as an improved water source because it is environmentally friendly and cost-efficient. In many cases, the springs we protect have already been used by the community as a water source for generations.

However, The Water Project has discovered over time that springs in Western Kenya are not always reliable year-round. In order to make sure that water is available at our springs throughout the year, our local teams conduct extensive vetting in the dry season to prioritize high-yield, non-seasonal springs for protection. While water point mapping included yield tests for all springs, we initially did not conduct all of the data collection during the dry season (January-March). So in quarter one of this year, our teams set out once again to do a full vetting of the mapped springs in Western Kenya. We found that only 411 of the 1,253 vetted springs met our reliability standards for TWP protection.

Our next mapping task was to fill information gaps around schools and healthcare facilities. These institutions were not mapped independently during the Western Kenya or Uganda mapping, but we eventually learned that this information is absolutely crucial to planning institutional water sources that can serve students striving towards education and those most vulnerable community members seeking treatment at health facilities.

Over the past few months, our teams in Western Kenya and Uganda set to work again to make sure that every school and healthcare facility was accounted for in our mapping and vetting system. In Western Kenya, this required coordination with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health for Kakamega and Vihiga counties, as well as with other NGOs who provide services at these institutions specifically. In Western Kenya, we vetted 586 schools and found that 23% were still in need of a safe and reliable water source. Of the 97 healthcare facilities vetted, 60% were found to be in need. In Uganda, we identified 12 schools in our focus region, 3 of which were still in need. All of these institutions will need to gain access to water before The Water Project can call our work done.

Enabling Local Leadership

As we mentioned earlier, the main priority for the water point mapping and vetting is to enable our local teams to make strategic decisions about future project planning. In order to make this information as accessible and useful as possible, we have developed interactive consoles in our water point management software, mWater. These consoles allow our teams to work with the data more dynamically and consolidate information from our various data collection efforts. This way of viewing the data also accounts for other key information like the functionality of existing TWP projects, planned project proposals, population density, and more. Perhaps the greatest strength of the consoles is real-time updating, so information automatically displays as it becomes available.

These water point mapping and vetting consoles have become a crucial tool for planning, as our teams are already working to identify projects for next year!

Engaging the Water Sector

The Water Project developed our water point mapping and vetting program to answer big questions about how to approach our goal of 100% coverage in communities, schools, and healthcare facilities. We’ve learned a lot along the way, and we know other organizations are likely asking themselves the same questions. Because of this, we have been eager to share our findings and methods with other water sector organizations.

One-on-one consultations with organizations in the sector have allowed us to share our methods while receiving feedback from people operating in different contexts. After a week-long water point mapping data bootcamp in Uganda last year, our friends at The Water Trust now use the coverage assessment and future project analysis methods to plan all of their work. This is typically over 100 new projects a year!

The Water Project also hopes to engage the broader WASH sector by participating in various conferences this year. Along with our partner Mariatu’s Hope, The Water Project submitted an abstract on our water point mapping and vetting program methodology to the UNC Water and Health Conference. This is one of the most exciting annual events for the WASH sector, as it provides a unique opportunity for researchers, implementers, and policy-makers to come together in one space. Two presentations related to what comes after mapping and vetting have already been accepted for presentation at the Water Engineering and Development Center Conference. One presentation, submitted in collaboration with our partner WEWASAFO, shares our learnings around the effect of eucalyptus trees on spring yield, and how this has been incorporated into the spring vetting system.

In Conclusion…

The Water Project prides itself on continuous learning as we strive to provide the best possible water services to those in need. Each time our teams go out to gather information, we learn a little bit more about the people we serve and gain a clearer vision of how to meet their needs. Because of this, we believe that water point mapping and vetting represent an investment in and a commitment to doing the work right.

Everything we learn brings us closer to our goal of 100% coverage — and to a world where everyone in our service areas has ready access to safe, reliable water. But our progress through water point mapping and vetting is just the beginning. Your generosity could help us transform lives faster through the power of water.

With over 450,000 people still in need of water in Kenya, Uganda, and Sierra Leone, we face a significant challenge. Your help can turn this challenge into an opportunity for change. Every donation helps us provide sustainable water solutions to communities, schools, and healthcare facilities that need them most.

Home More Like ThisTweet