A normal day in Karongo begins as early as 6am, when men wake up to arrive at the Kinyara Sugar Factory on time for work. Most work on the sugarcane plantations cutting down cane that is ready for processing. Women tend to remain at home to work in their gardens to get enough food to put on the table. Maize, 'matoke' (plantains) and beans are most popular. Any excess is sold in the Towasaati and Kabango markets. Beyond this, women are also expected to watch the children and do all of the household chores.

In the evenings, men like to go to the trading center to socialize with their friends before dinner. Dinner here is prepared fairly late, with families eating at about 9pm before bedtime.

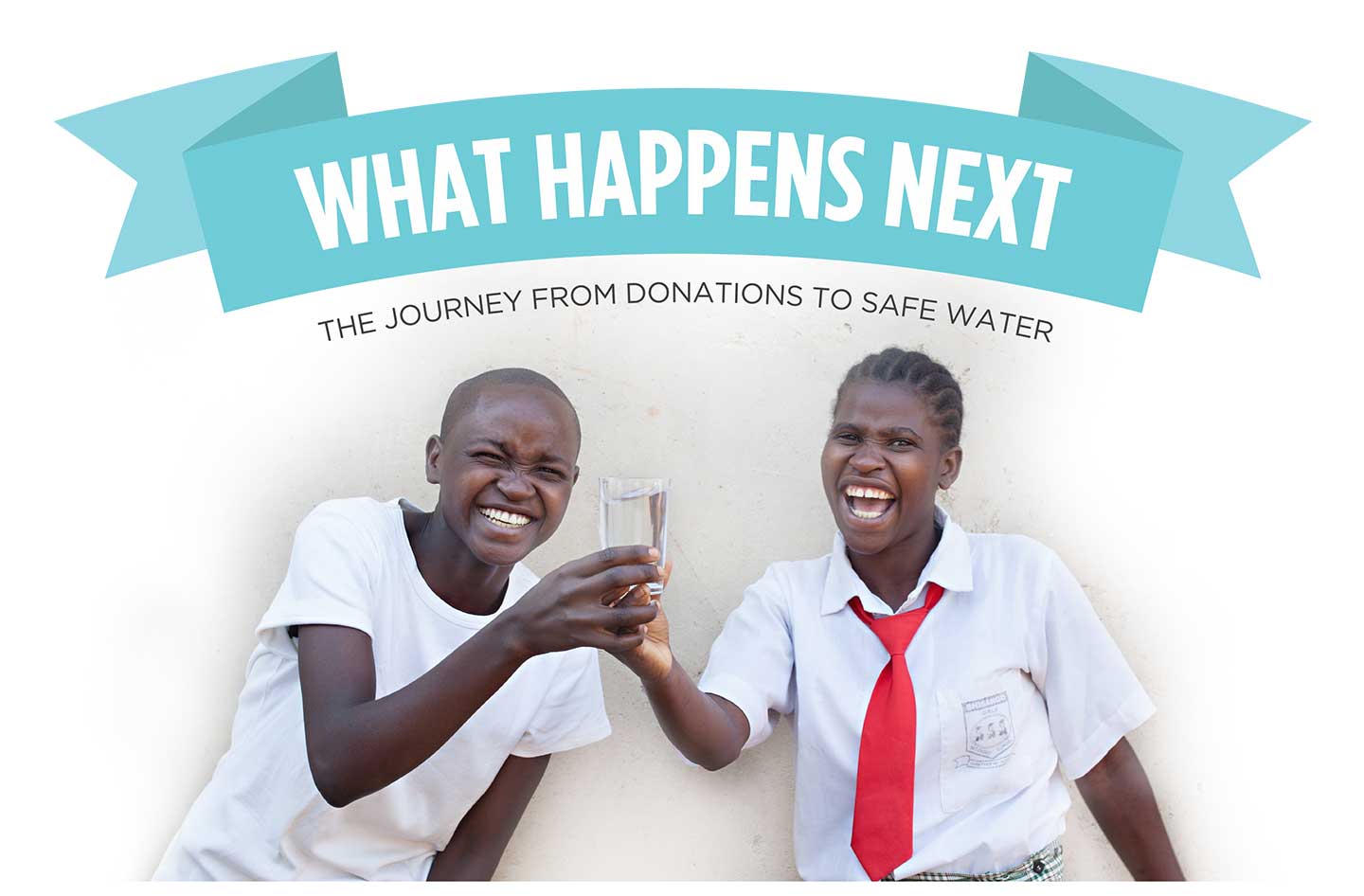

One of the biggest challenges in Karongo is the pull to make more money. Most youth here have dropped out of school to cut sugarcane.

But one of the special things about Karongo is the great level of teamwork; farmers help each other prepare fields for sowing each year.

Water

People living in Karongo rely on surface water to meet all of their needs. An open, unprotected spring brings water to the surface. Locals use a wooden board as a bridge, suspended over the widest part of the spring. Standing in the middle, one can balance and scoop up the clearest water available – away from the cloudy, algae-covered banks.

But no matter where you stand and fetch your water, there’s no doubt this spring is contaminated. Animals are free to come and sate their thirst. The water smells, and people who drink it complain of constant diarrhea. Children under five struggle to fight the strain this dirty water puts on their bodies.

Mr. Jadri Robert told us that "there are high cases of skin infection because of the kind of water being used by the community members is not safe. Diarrhea cases are also high, hence a lot of money and time is spent on treatment."

Sanitation

Less than half of households living in Karongo have a pit latrine, most of which are made of mud walls and have no doors or roofs. Because of these poor conditions, open defecation is a big issue here, with people seeking the privacy of farms and brush to relieve themselves. Flies, animals, and rainwater then spreads this contamination throughout Karongo – even to the spring from which people fetch drinking water.

When asked why so few people have pit latrines, they complained that they simply don't have the tools they need to dig with.

Here’s what we’re going to do about it:

Training

Training’s main objectives are the use of latrines and observing proper hygiene practices, since these goals are inherently connected to the provision of clean water. Open defecation, water storage in unclean containers and the absence of hand-washing are all possible contaminants of a household water supply. Each participating village must achieve Open Defecation Free status (defined by one latrine per household), prior to the project installation.

This social program includes the assignment of one Community Development Officer (CDO) to each village. The CDO encourages each household to build an ideal homestead that includes: a latrine, hand-washing facility, a separate structure for animals, rubbish pit and drying rack for dishes.

We also implement the Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) approach with each of our village partners. This aims to improve the sanitation and hygiene practices and behaviors of a village. During these sessions, village leaders naturally emerge and push the community to realize that current practices of individual households – particularly the practice of open defecation– are not only unhealthy, but affect the entire village. CLTS facilitates a process in which community members realize the negative consequences of their current water, sanitation and hygiene behaviors and are inspired to take action. Group interactions are frequent motivators for individual households to: build latrines, use the latrines and demand that other households do the same.

Spring Protection

Over continued visits to the community, the viability of a hand-dug well diminished. We just couldn’t find a good construction site for a well that would yield safe, clean water. The terrain here is very hilly; a great place for flowing springs but a difficult place to dig a well.

Considering the convenience, reliability, and long history of this spring, the community has decided to unite with us to build a spring protection system for their current source. Once construction is completed, the spring will begin yielding clean drinking water.

There’s a lot of work to be done: Community members will have to help our team clear the land around the spring, diverge the water, build a catchment area with walls allowing for discharge pipes and steps in and out, and dig drainage. Local families will host our spring protection artisans while they begin the sanitation improvements needed for a successful partnership. We all look forward to making these improvements together!

This project is a part of our shared program with The Water Trust. Our team is pleased to provide the reports for this project (formatted and edited for readability) thanks to the hard work of our friends in Uganda.

Protected Spring

Protected Spring

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project