What makes a water project sustainable?

We get this question a lot at The Water Project, and maybe you’re scratching your head right now wondering the same thing. We could give you answers like, “We only contract with reputable builders,” or “We strive to use only the best materials,” — which technically are both true — but the complete answer is actually more complex.

The reality is that a single water point — a well, a rain tank, or any other type of water project — just isn’t a long-term solution for any community, and for that reason, we always develop a more comprehensive plan before starting a project. So, today, we’re going to respond to a slightly different question: “What makes a water system sustainable?”

Why a water system? What even is a water system?

When we donate to provide safe water access in sub-Saharan Africa, maybe we imagine installing one well per community, enlisting all the local stakeholders to care for that well, and calling it good.

But if that one water source breaks down, community members could be left with their previous unsafe water options.

“When I first entered the water access sector, I believed sustainability was primarily about infrastructure that lasts,” said The Water Project’s Director of Program, Spencer Bogle.

“If the well didn’t dry up or the pump kept working, it was a success. But years of fieldwork have taught me that sustainability is about community buy-in and reliable systems.”

So, what is a water system? In our service area, this can be difficult to envision; what it definitely isn’t is the interconnected network of pipes and sewer lines that most of us are familiar with.

Instead, said Spencer, “It’s about people knowing how to manage, maintain, and advocate for their own water access — not just for today, but for generations. It is about the ways people use water within their daily lives — in school, healthcare, finances, and government — and monitoring and maintenance systems.”

Every sip of dirty water is a risk. Sometimes, that single sip is all it takes for someone to get seriously ill. This is why we should think of water as an interwoven network of safe water sources — and not narrow our concern to the fate of each individual source.

“Sustainable access to water is complex,” Spencer said. “Most people use multiple water sources daily. That insight has reshaped how we think about projects — not as isolated installations, but as integral parts of a community’s larger water ecosystem.”

Why don’t governments provide sustainable water utilities?

Well, they do — sometimes.

If your tap stopped working, you’d expect a utility to send someone to fix it. But in the places where we work, governments simply can’t extend that kind of service.

In the areas we serve, the local government often builds a utility grid and offers paid services. However, a system like this in the places we work invariably serves only the wealthy, and not the people we aim to help.

“That’s not an option,” Spencer said.

The populations we serve don’t live within reach of established utilities, and their governments don’t have the capacity to extend them. So, we build a similar utility — one that doesn’t rely on the community members’ ability to pay expensive fees — from the ground up.

We do this through a network of sustainable water access points. We commit to monitoring, community engagement, and establishing responsibility. We answer questions like, “Who do community members call when it breaks?” “Why did it break down?” “How do we fix it?” “How can we get people access to quality resources and mechanics?”

As Spencer said: “It’s not efficient or economically viable to commit to only one project.”

So, how does one maintain a water system?

“At The Water Project (TWP), we believe sustainability starts with listening and connecting with those who are closest to the problems that reliable water can address,” Spencer said.

“We focus geographically to maximize impact within a set budget. We commit to routine monitoring and invest in infrastructure that starts with reliable groundwater sources.

“But most importantly, we commit to people. TWP uses two service models: Community Management (in Uganda and Southeast Kenya) and Professional Dispatch Services (in Western Kenya and Sierra Leone).

“In Community Management, we engage communities from the very beginning — forming Self Help Groups that link Water User Committees (WUCs) and Village Savings and Loans Associations (VSLAs). These groups learn everything from water system governance to repair budgeting. They are responsible for saving money for repairs and directly contacting local mechanics.

“In Professional Dispatch areas, Water User Committees contact a TWP regional hub staffed with mechanics and engineers who respond quickly to breakdowns — often within 24 hours. This approach ensures rapid technical support while maintaining community trust.”

“Ultimately, sustainable water systems require access to quality construction, quality parts, and long-term financial support, ideally in the form of communities who are willing and able to pay for services to keep the water running.

“However, the only way to know if the work is effective is to monitor. We have developed a robust Monitoring, Evaluation, Resolution, and Learning department that allows us to see when things break down and how we can improve design, training, and issue response.”

“Sustainability of WASH services is the central premise of global WASH efforts.” (UN WASH Accountability for Sustainability Programme)

Monitoring and maintenance aren’t just good practice — they are the very heart of ensuring water systems remain safe and reliable for the long term.

Who else needs to be involved?

“Our focus on full water coverage aligns with national, county, and district development plans,” Spencer explained. “We’ve formalized these partnerships through Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs), which help build credibility and ensure alignment with broader public sector efforts. Local government officials often become invaluable partners in long-term support.”

For example, one of our longest-standing relationships is with the local governments in our Western Kenya service area.

“The Water Project program, I would say, has played a major, crucial role in our county,” said Dr. Wilber Ottichilo, Governor of Vihiga County in Western Kenya.

Dr. Ottichilo continued: “And I would say The Water Project is our premium partner in this endeavor of providing water to our people. I’m grateful, on behalf of the people of Vihiga, to The Water Project program. I think they have done a commendable job. It’s so evident that the partnership that is existing between The Water Project and the county government is strong, and we believe that it’s going to last for so many years.

“The Water Project have never come to impose themselves [on] our county. They have come to us, and we have sat down, and we have agreed on our priorities. Normally, many other development partners come, and they decide what they want, and in many cases, they don’t even involve the leadership. But in terms of The Water Project, they came to this office, so they engage the highest decision maker in the county. So, it’s been a consultative effort.

“The Water Project also engages the community. Our main principle of county government is public participation, engaging people in the decision-making process. And I believe, and I’m very happy that The [Water] Project has been very instrumental to ensure that they do public participation before the project is implemented. So that means there is ownership of the project when they leave. The project should be owned by the recipients, who are the community.”

How does TWP keep sustainability in mind at each project stage?

Mapping/Siting

Before we even think about building a new water source, we consider each community’s unique water situation. For this, our water point mapping exercises have been invaluable.

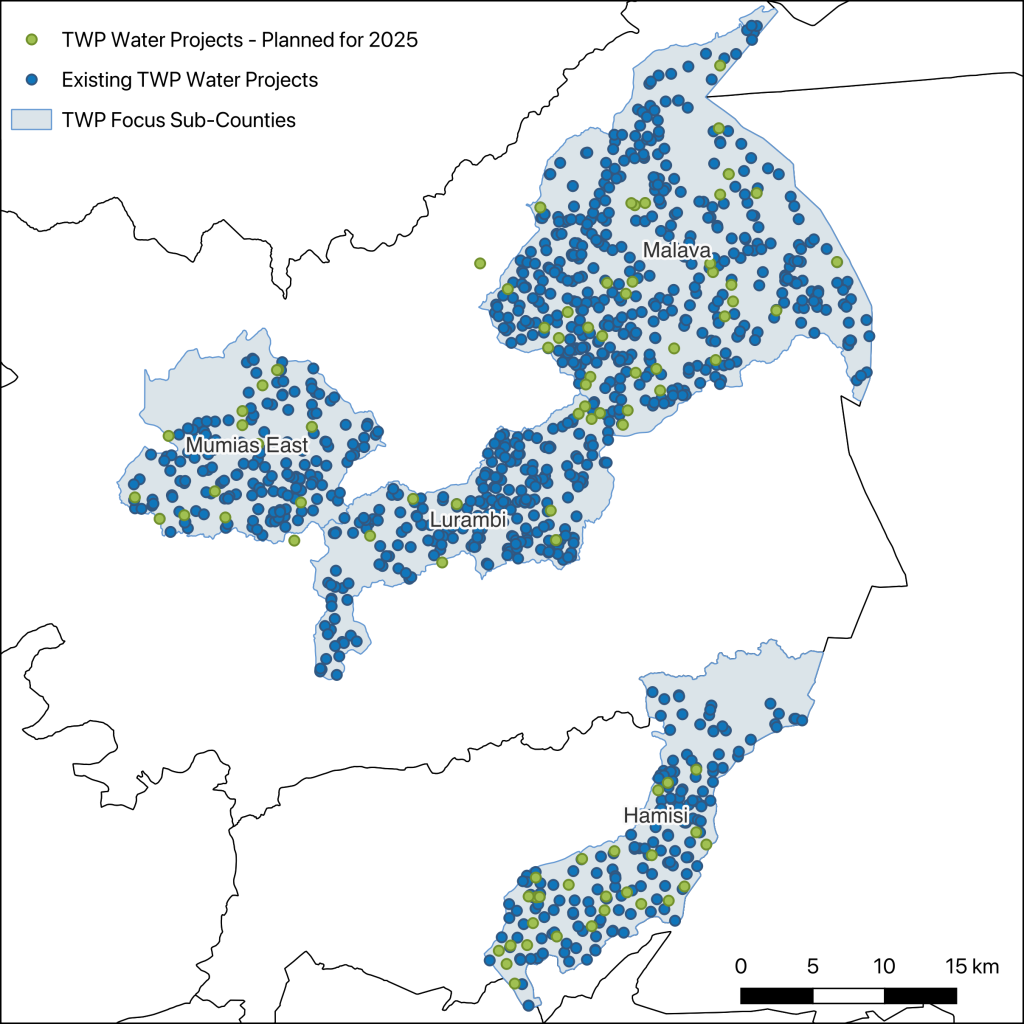

“We have worked together with local community leaders and officials to map public water points in each of our service areas,” Spencer explained. “This allows us to see areas in need and to create networks for water points to ensure access and to make monitoring and maintenance more efficient.”

When vetting a new water source, we evaluate several factors. First, we assess its current state, including its functionality, yield, and environment. A technical assessment of any existing infrastructure helps us identify issues that may make the source vulnerable to contamination or breakdown.

While our local teams use mapping data as a jumping-off point, they also engage deeply with communities to ensure that the water sources will meet community needs. Because mapping provides only empirical data, we also take into account the community’s preferred water source, land ownership concerns, social dynamics within the community, and the environmental factors that determine which source type will be possible.

We prioritize communities that reach out to express their need for water. Requesting support shows the kind of community ownership and organization that often makes a project even more successful in the long term.

Next, we test the water yield — how much water the source produces. For rain-dependent sources, such as springs, we test during the dry season when water flow is at its lowest. Finally, we conduct a sanitary inspection of the waterpoint’s surroundings to identify possible sources of contamination, such as nearby latrines or farms using fertilizer.

Mapping an entire region’s water resources informs our strategy for establishing future plans, and the local government also benefits.

Proposal & Construction

With a solid foundation of community engagement and education, we move forward with the physical implementation. Whether it’s drilling a well, constructing a sand dam, or installing a rainwater catchment system, our team of experts ensures that the chosen solution is implemented with the highest standards of quality and efficiency.

“We build for the long haul, with community input, siting to ensure reliable groundwater availability, quality materials, and trained professionals,” Spencer said.

In many cases, we ask the community, school, or health center to contribute locally available construction materials like sand and stone to a project’s construction. This helps speed up the construction process and promotes community buy-in and ownership. If people are involved in a project’s construction, they may also be better able to identify issues with a water source once it’s completed.

For more information on project-specific construction processes, read this blog about the journey of a water project.

Training & Handover

“Communities receive governance and management training, hygiene and sanitation training, and water point maintenance protocols,” Spencer said.

For every water point we construct, we help establish a Water User Committee made up of local residents who will oversee and manage the water point. These committee members receive training on the proper use and maintenance of the water system and financial management (so they can collect fees for small repairs and maintenance). This ensures the community has the knowledge and resources to keep the project running independently.

Monitoring & Maintenance

Many people assume the completion of construction marks the end of our involvement. Actually, the opposite is true. In the very first quarter after a water point’s installation, we return to check that the water source is still providing water — and then we come back, again and again.

“Our teams monitor each water point quarterly, test water quality biannually, and work to ensure that breakdowns are repaired within 72 hours,” Spencer said.

“It is much more cost-effective to maintain and repair water points than to replace them. Timely maintenance can only happen when breakdowns are reported quickly, and communities will only report issues if they trust that the problem will be addressed honestly and professionally.”

When we identify a water point malfunction, such as a breakdown or necessary repair, our software flags the survey and we prioritize a service visit.

Community Care

Through ongoing monitoring, maintenance, and education, we continue to support communities as they manage their water points, fostering independence and long-term success.

“Beyond infrastructure, we invest in relationships that sustain the work,” Spencer said. “Communities contribute to maintenance and repair either by paying into a subscription service or as needed for parts and service from a Self-Help Group fund.”

How does TWP help communities take ownership of their water points without burdening them with expensive service fees?

“The answer lies in context,” Spencer said. “In some areas, community-linked savings groups pool funds specifically for repairs. In others, TWP handles the service directly, subsidizing the repair costs heavily, ensuring that systems remain functional while we work on longer-term cost-recovery models.

“It’s never one-size-fits-all, but every approach aims to empower without overburdening. We understand that people will not pay for a service until it is reliable enough for them to see the value of having consistent access to safe water.”

Will my gift to build a water project through TWP make a lasting difference?

In a word? Yes.

“At TWP, we measure results, report transparently, and stay with communities long after construction ends,” Spencer said.

“We are committed to relationship, reliability, and trust in every part of our work. We build durable systems where people, not just hardware, are the foundation. Because we are committed to continuous learning, communication, and collaboration to constantly improve our work, services, and relationships, we are confident that communities will flourish because of the reliable water that we provide for the long term. That’s what sustainability means to us. And that’s why we know the water will keep flowing.”

Creating sustainable projects throughout Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Uganda is only possible with the support of generous people like you. The easiest way you can boost the sustainability of our water points is to regularly support our Water Promise.

Home More Like ThisTweet