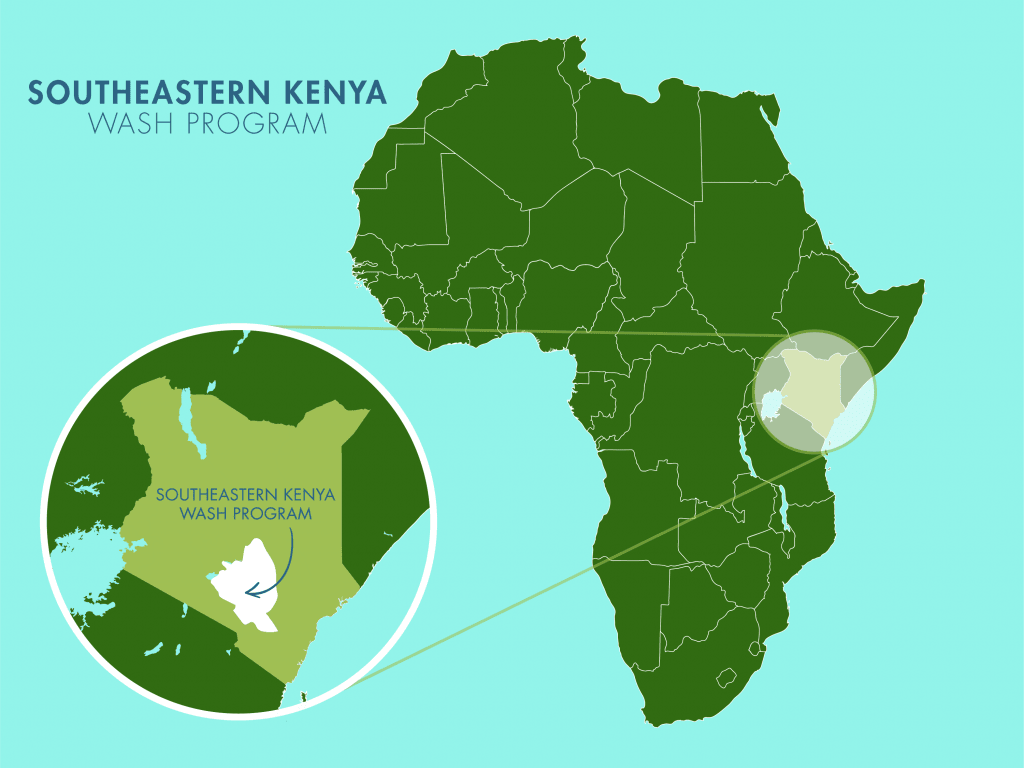

In the heart of the Wikwatyo wa Aka Kilulu Community, a determined group of 300 residents has endured years of water scarcity amid the region’s harsh, rocky terrain. Despite their resilience and resourcefulness, accessing safe water remains one of their greatest daily challenges.

The community relies primarily on two distant sources: a protected dug well and open scoop holes along a dry riverbed. On average, residents spend 30 minutes to two hours walking back and forth to fetch water—time that would otherwise be spent farming, caring for children, or earning an income. The steep, dusty paths and the unforgiving sun make every journey physically exhausting, particularly for women and children who bear the brunt of water collection duties.

While the dug well offers relatively cleaner water, it is often low during the dry season and is located far from many homes. The scoop holes dug in dry riverbeds, meanwhile, pose serious health and safety risks. They are unprotected, easily contaminated by animal waste and runoff, and surrounded by debris. The water there, though clear, has a saline taste and unpleasant odor, a constant reminder of its unsuitability for safe drinking.

A community member fills her jerrycan from a local scoop hole.

Field Officer Alex Koech observed that not everyone owns a donkey to help carry water, forcing most residents to haul heavy jerrycans by hand or shoulder them over treacherous terrain. For many, fetching water has become a test of endurance.

The cost of this struggle extends far beyond fatigue. Drinking from scoop holes has led to repeated cases of typhoid, amoeba, and diarrhea in the community. The contaminated water, mixed with animal waste and farm runoff, poses a threat not only to health but also to productivity.

The act of collecting water itself has social and economic consequences. Women spend long hours walking to and from water sources, leaving them with little time to tend to their farms, run small businesses, or participate in communal savings groups. Children often assist their parents, particularly during school holidays, sacrificing rest, play, and study time.

Without reliable access to clean water, residents are forced to ration every drop of water. Hygiene and sanitation suffer, and families are left vulnerable to preventable illnesses that drain limited incomes and hope.

Among those living this reality is Tabitha Simon, a 41-year-old farmer and mother whose daily routine revolves around the pursuit of water.

Tabitha Simon.

Each day, Tabitha makes a single trip to the scoop holes—a two-hour round journey—because the terrain is so steep and the process so draining that repeating it is nearly impossible. The burden leaves her with little time for the farming activities that sustain her family’s livelihood.

She explains the core of their problem clearly: “The main problem is that our village is in a very dry area, and the terrain is steep and rocky. The scoop holes we rely on are in seasonal rivers that dry up quickly. During drought periods, the water goes too low, and with everyone in the area depending on the same point, it gets used up fast. The situation worsens because the terrain makes it very difficult to carry large amounts of water, especially for those who don’t own donkeys.”

What troubles her most, however, is the condition of the water itself.

“I'm deeply concerned about our current water source because it’s just a scoop hole, open to animals and human activity. The water is not protected in any way. There is animal waste and debris around the area, and the water is often dirty. I know that every time my family drinks that water, there’s a risk of falling sick with things like typhoid, amoeba, or diarrhea. As a mother and community member, it's painful to see our children exposed to that kind of danger just because we don’t have a better alternative," Tabitha shared.

Her words capture the deep anxiety shared by many, an anxiety that comes from knowing the daily water they depend on is unsafe, yet unavoidable.

Tabitha works to provide for her family.

Still, Tabitha holds hope for change.

And when asked what water means to her, her answer is both simple and profound: “To me, water truly is life. Without it, we can’t cook, clean, farm, or even care for our animals. My children’s health depends on clean water. My ability to grow vegetables or take care of my livestock also depends on water. When we don’t have enough, everything in life feels harder—our health suffers, our income drops, and our spirits fall. But with water, our lives are easier to live, plan for the future, and live with dignity.”

“A new water point—like a sand dam—will bring clean and safe water much closer to home. With protected water that’s stored under sand and away from contamination, I won’t have to worry about my children getting sick every time they take a sip. We will also no longer struggle carrying heavy jerrycans across steep, dusty terrain under the hot sun. That safety, both health-wise and physically, will bring us peace of mind and more time to care for our farms, livestock, and families.”

When we asked Tabitha how she foresees the future with access to clean water being different, she said, “I would use my time to take care of things at home, like cooking for my children, herding the goats, or preparing my farm for the next rain season. I would also get time to interact with my neighbors and practice table banking more effectively.”

For Tabitha, clean water represents safety, health, and freedom—the ability to live without fear of sickness and to reclaim time for family and community life.

Tabitha at the distant well.

The proposed sand dam will bring lasting relief. By capturing seasonal rainwater within the sand, the new structure will provide a reliable and clean water supply year-round.

This solution will dramatically reduce the distance and danger of fetching water, restore time for livelihoods like farming and livestock care, and improve public health by reducing exposure to contaminated sources.

The Wikwatyo wa Aka Kilulu SHG envisions a future where access to water fuels progress rather than hinders it. With a consistent nearby supply, members plan to establish vegetable gardens, plant trees, improve livestock management, and terrace their lands to prevent soil erosion. These activities will not only improve food security but also enhance income generation and environmental resilience.

Clean water will empower the community to focus on development rather than survival—to farm, learn, and live with dignity. For Tabitha and her neighbors, a new waterpoint represents more than convenience. It means health instead of illness, time instead of exhaustion, and hope instead of hardship.

Solving the water crisis in this community will require a multifaceted system that will work together to create a sustainable water source that will serve this community for years to come.

Steps Toward a Solution

Our technical experts worked with the local community to identify the most effective solution to their water crisis. Together, they decided to construct a sand dam and a protected dug well.

Sand Dam

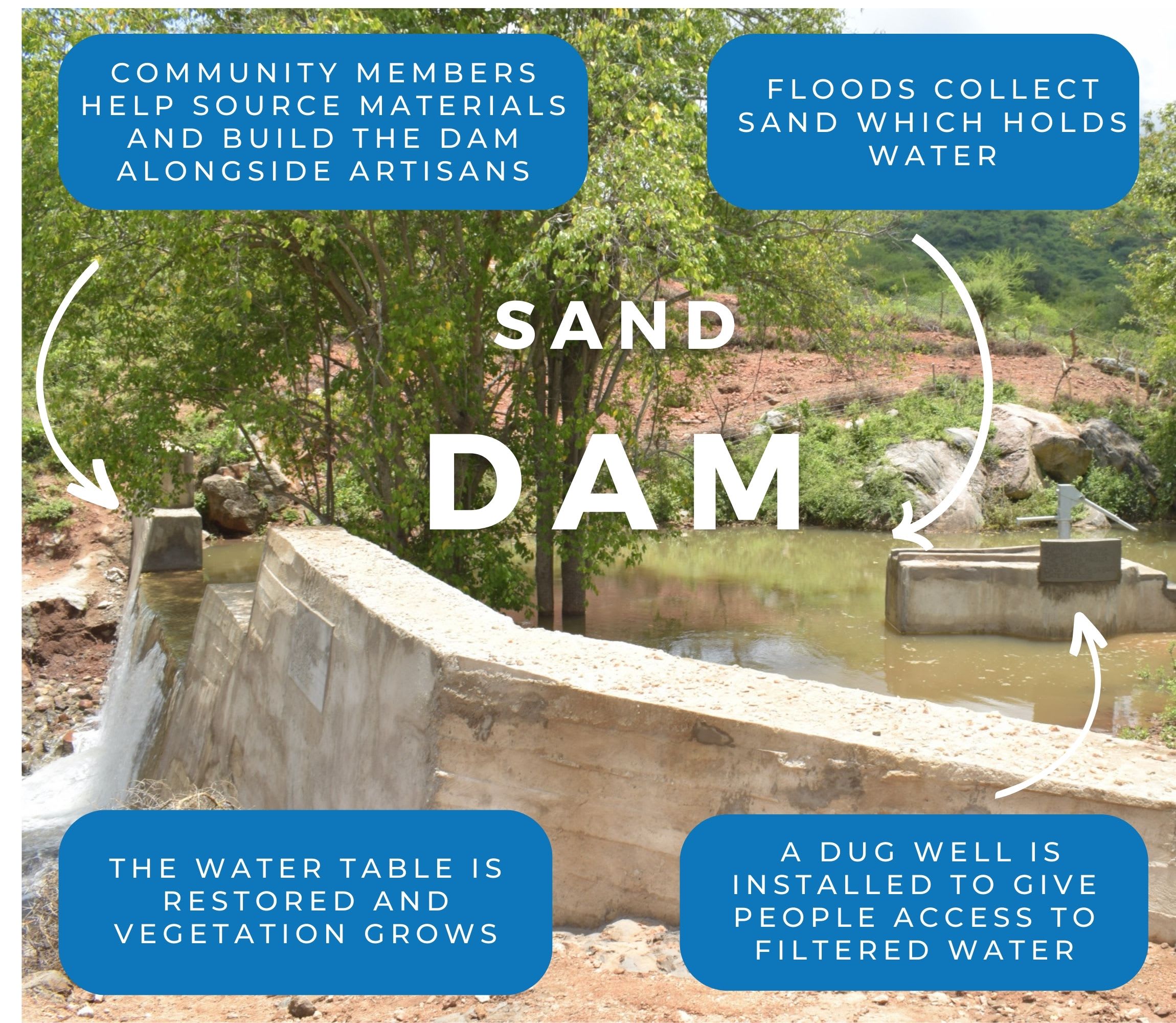

Sand dams are sought-after, climate-smart, and lasting water solutions providing hope and resilience to communities in arid Southeastern Kenya. Think of them like giant sandboxes constructed in seasonal rivers that would typically quickly dry up after the rainy season. Instead of holding water like traditional dams, they collect sand and silt.

When infrequent rains do come, these dams catch a percentage of the river's flow, letting most of the water continue downstream to other communities. But here's the magic: the sand they collect acts like a natural filter, holding onto water long after the river's gone dry. Then, wells are constructed nearby, creating a reliable water source even during the driest times.

And the benefits don't stop there! In communities impacted by climate change, sand dams replenish groundwater and prevent soil erosion. Even during severe droughts, the consistent water supply from these sand dams allows farmers to thrive, giving way for enough food not only for their families but also to sell in local markets.

The most remarkable aspect of sand dams is how they involve the local community every step of the way, giving them a sense of ownership and pride in solving their own water shortage and managing their own water resources.

This sand dam will be connected to a protected dug well to make the water more accessible.

What Makes This Project Unique

At sand dams that meet the technical requirements, we make pre-investments in pump infrastructure where sand dams are suitable for piped supply. The design includes a concrete pump house that is accessible even after the dam matures, allowing for future installation of a submersible, solar-powered pump. This setup facilitates the transportation of water uphill to kiosks or networks of kiosks in future projects.

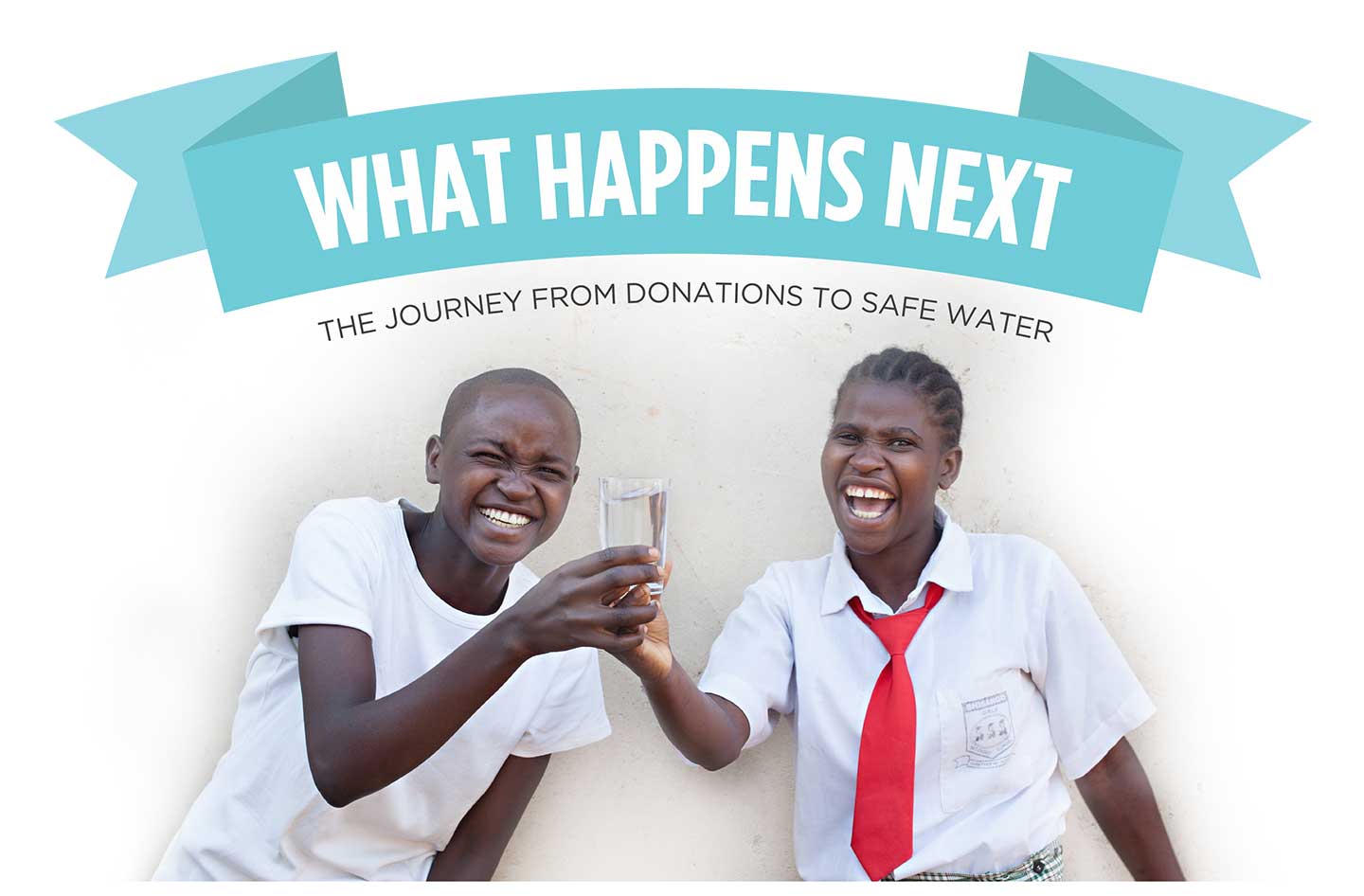

Community Education & Ownership

Hygiene and sanitation training are integral to our water projects. Training is tailored to each community's specific needs and includes key topics such as proper water handling, improved hygiene practices, disease transmission prevention, and care of the new water point. Safe water and improved hygiene habits foster a healthier future for everyone in the community.

Encouraged and supported by our team's guidance, the community elects a water user committee representative of its diverse members. This committee assumes responsibility for maintaining the water point, organizing community efforts, and gathering fees to ensure its upkeep.

Sand Dam

Sand Dam

Rehabilitation Project

Rehabilitation Project